3. Places in Music.

Musical landscape painting became a stock-in-trade of many Romantic composers. Some depicted the lands in which

they lived: think of Smetana in Bohemia or Sibelius in Finland. Others sent musical dispatches home from other

places: Mendelssohn from Scotland, Dvorak from America, Gershwin from Paris.

But music alone is seldom sufficient to tie a work to a specific place; it needs a title, or some other clue that

will point listeners elsewhere. Often this is a reference to the folk music or dance of another region. This was

how Copland made the mental trip from Brooklyn into the Wild West world of Billy the Kid. It was how

English composers of the early 20th century such as Holst and Vaughan Williams found the key to revitalizing

English music as a living force. But since many of the traditional folk songs that they unearthed would be lost

when the last generation that knew them passed away, their portrayal of contemporary England was also a memorial

to a life that was quickly slipping into the past.

The script, videos, and images will be posted immediately after class.

FURTHER THOUGHTS

In both this and the previous class, I have been looking into the question of labelling, or the various kinds of

information we may need to identify a piece as referring to a specific period or locale. But the title of the course is

Musical Escapes, not Musical Archaeology. Do we need specific labels for the music to take us out of ourselves,

and if not, what do we need?

Of all the pieces we played, which do you think are most successful at giving you that escape? My own choices would

be the Karelia intermezzo, The Moldau, both Billy the Kid and An American in Paris, plus (for

me as a Brit) Holst's Somerset Rhapsody. What do these things have in common? At least one good tune. A strong shape

that builds to a climax and lets you down gently. And a general descriptive quality that seems to fit the title—once you

know what it is—like the rippling figures in the Moldau or the taxi horns in Paris. Perhaps such things are

all you need.

By deliberately choosing videos with dated elements, I admit I shaded the issue to claim that some of these pieces were

also about time. In most cases, though, the images merely reinforce what is already present in the music. The old

castles in Karelia echo an old-time quality in that heroic march. The faded postcards I used for A Somerset

Rhapsody reflect folk songs that are no longer in circulation, and music that seems to emerge from a distant mist.

Only in the use of World War images for the second video of A Shropshire Lad (alas no longer available) was the film

editor imposing ideas on the piece that could not have been conceived when it was written. And yet, and yet… Butterworth's

work is based on a set of poems that read as an elegy for lost youth. And even when we select modern views to accompany these

evocations of the English countryside (including Vaughan-Williams and Holst), we have to work to find those with the least change.

For any of these pastoral pieces is essentially a time-capsule, preserving an aspect of English life that, even then, the

composers knew would not last. rb.

VIDEO LINKS

Almost all the clips shown in class are available on YouTube. The exceptions are the video of Butterworth's Shropshire

Lad with the WW1 references, which I greatly regret, and the shipboard chorus in Anything Goes—though I have put

in the Act I finale from the same production.

Most things shown in short clips in class are represented here by their full versions; this includes the folk songs and

other brief excerpts used in my animated titles. Complete additions include alternate versions of some of the videos, and a

couple of interesting posts on how Copland manipulates the cowboy songs used in Billy the Kid. I remarked that George

Butterworth did not use folk music in the Shropshire Lad rhapsody, but based it on a song of his own, "Loveliest of

trees." I include that song, plus a lovely idyll by Butterworth, Banks of Green Willow, in which he does use folk music.

All such additions are *asterisked.

| A. HERE, THERE, WHEN, WHERE? |

| |

Sowande: African Suite |

|

* Complete

(Archestra Project, Berlin)

* — finale: Akinla

(Ubuntu Ensemble, London)

|

| |

Sibelius: Karelia Suite |

|

* Complete

(Munich PO, Järvi)

* Intermezzo

(landscape video)

* — the same

(historic video)

|

| |

| B. FROM EASTERN LANDS |

| |

Bartok: Romanian Folk Dances |

|

* Complete, cued to end

(Norwegian Chamber Orchestra)

|

| |

Liszt: Hungarian Rhapsody #2 |

|

* Complete, cued to fast section

(Valentina Lisitsa)

|

| |

Janacek: Danube Symphony |

|

* Parts I & 2

(landscape video)

* Complete

(audio only)

|

| |

Smetana: Ma Vlast |

|

* Vltava

(landscape video)

|

| |

Borodin |

|

* In the Steppes of Central Asia

(landscape video)

* Prince Igor

(Paris Opéra; cued to dances)

|

| |

[Borodin] Kismet |

|

* Stranger in Paradise

(Vic Damone, from the film)

* — the same

(Sierra Boggess & Julian Ovenden, COVID)

|

| |

| C1. SCOTLAND |

| |

Gaelic folk songs |

|

* Hug Air a' Bhonaid Mhoir

(Julie Fowlis)

* Wild Mountain Thyme

(Sarah Calderwood)

|

| |

Mendelssohn |

|

* Hebrides overture

(hr-Sinfonie, Andres Orozco-Estrada)

* — my video with Turner picture

* Scottish Symphony, scherzo

(hr-Sinfonie, Andres Orozco-Estrada)

|

| |

| C2. AMERICA |

| |

Dvorak: New World Symphony |

|

* Largo

(hr-Sinfonie, Andres Orozco-Estrada)

* Scherzo

(as above, complete symphony)

|

| |

Copland: Billy the Kid |

|

* Orchestral suite

(NYO2, cued to start in class)

* Copland's use of songs

(talk by Adam Stern)

* Website with cowboy songs

|

| |

| C3. TRANSATLANTIC |

| |

Porter: Anything Goes |

|

* Act I finale, title song

(Suttton Foster, Barbican)

|

| |

Gershwin: An American in Paris |

|

* Complete

(hr-Sinfonie, Giedre Slekyte)

* — as above, cued to Blues

|

| |

| C4. ENGLAND |

| |

Song: "High Germany" |

|

* Martin Carthy

(audio with words)

|

| |

Vaughan-Williams: Folk Song Suite |

|

* Complete

(complete suite, in a different video)

* Final movement

(video by RB)

|

| |

Holst: Somerset Rhapsody |

|

* Complete

(video by RB)

|

| |

Housman: A Shropshire Lad |

|

* Is my team ploughing?

(read by Peter Brown)

|

| |

Butterworth: A Shropshire Lad |

|

* Song: "Loveliest of trees"

(Roderick Williams)

* Orchestral rhapsody

(landscape video)

|

| |

Butterworth: Banks of Green Willow |

|

* Idyll for orchestra

(landscape video)

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| IMAGES |

The thumbnails below cover the slides shown in class, though

there may be a few small discrepancies. Click the thumbnail to see a larger image.

Click on the right

or left of the larger picture to go forward or back, or outside it to close. |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

Here are brief bios of the composers and writers considered in the class, listed in order of birth.

|

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy, 1809–47. German composer.

A major figure in the Romantic movement and a precocious talent, he wrote many of his best-known works (such as the Midsummer Night's Dream overture) while still in his teens. By virtue of his ten separate residencies in England or Scotland, and the works he premiered there, he almost qualifies as a virtual British composer.

|

|

Franz Liszt, 1811–86. Hungarian composer.

Liszt was the foremost piano virtuoso of his time, playing three or four concerts a week during his heyday during the 1840s, and much of his prolific output—including notably his set of 19 Hungarian Rhapsodies—is designed for display. But he was also a generous supporter of numerous other musicians, including Chopin, Schumann, Berlioz, Grieg, Borodin, and Wagner (who became his son-in-law). Many of his compositional techniques in his later works paved the way for advanced composers at the turn of the century,

|

|

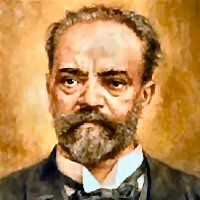

Bedrich Smetana, 1824–84. Czech composer.

Known as the "father of Czech music," his works Ma vlast (My Homeland) and The Bartered Bride most clearly exemplify the tide of Romantic Nationalism, but only a small portion of his works have entered the international repertoire.

|

|

Alexander Borodin, 1833–87. Russian composer.

A medical doctor and research chemist, he only composed music as an amateur (as did many of his contemporaries in the "mighty handful"). But works like his tone poem In the Steppes of Central Asia (1889), his unfinished opera Prince Igor, and some of his chamber music sing in a distinctive and often haunting Russian voice.

|

|

Antonin Dvorak, 1841–1904. Czech composer.

The best known of Czech composers, Dvorak composed nine symphonies and numerous chamber works. From 1885 to 1888, he was director of a new conservatory in Manhattan; he later became director of the conservatory in Prague. Of his ten operas, only the fairy-tale Rusalka (1901), a variant on the Little Mermaid story, has had true international success, cropping up in an astonishing range of productions in the last few decades.

|

|

Leoš Janácek, 1854–1928. Czech composer.

Janácek turned to opera fairly late in his career, but his half-dozen mature works in the medium place him in the forefront of opera composers of the 20th century, not only for their distinctive musical style but also their unusual structure and dramatic innovation. Among them are: Jenufa (1903), Káta Kabanová (1921), The Cunning Little Vixen (1923), The Makropoulos Affair (1925), and From the House of the Dead (1928).

|

|

AE Housman, 1859–1936. English poet and scholar.

A classics professor at Trinity College, Cambridge, AE (Alfed Edward) Housman played down his work as a poet, yet his 1896 collection A Shropshire Lad captured public attention, both for its picture of rural life in Shropshire and for its persistently elegaic tone that caught the malaise of the end of the century and proved eerily prophetic of the First World War.

|

|

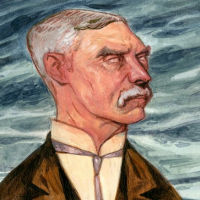

Jean Sibelius, 1865–1957. Finnish composer.

Sibelius "is widely regarded as his country's greatest composer, and his music is often credited with having helped Finland develop a national identity during its struggle for independence from Russia" [Wikipedia]. In addition to his seven symphonies, at least two of which have become repertoire standards, he wrote a number of tone poems based on Finnish history and myth, such as Finlandia, Tapiola, the Lemminkainen Legends, and the Karelia Suite.

|

|

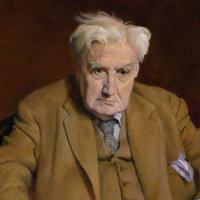

Ralph Vaughan Williams, 1872–1958. English composer.

Associated with the English folk song revival, he was more than anybody responsible for giving English music its national voice. He wrote nine symphonies and numerous vocal works, including the one-act opera Riders to the Sea. His first name is pronounced "Rafe."

|

|

Gustav Holst, 1874–1934. English composer.

The son of a church organist of Swedish descent, Holst studied first the piano and then the trombone. With Ralph Vaughan Williams, he was largely responsible for the revival of interest in English folk music at the turn of the century. He worked most of his life as a church musician and in education, but wrote numerous works, of which The Planets (1918) is the largest and most famous.

|

|

Béla Bartók, 1881–1945. Hungarian composer and ethnomusiclogist.

One of the most important composers of the early 20th century, Bartok forged his own path, combining an exhaustive study of Eastern European folk music with a personal modernism that was never doctrinaire. His early opera Duke Bluebeard's Castle (1911) is a landmark of musical expressionism. Important later work includes 6 ground-breaking string quartets, 3 piano concertos, 8 volumes of progressively challenging piano pieces he called Mikrokosmos and his late Concerto for Orchestra. He died in NYC.

|

|

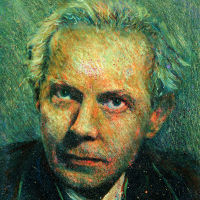

George Butterworth, 1885–1916. English composer.

Critics have suggested that Butterworth might have become the greatest of the generation of composers that included Vaughan-Williams and Holst, had he not been killed on the Somme in his early twenties. Like his contemporaries, he collected folk song and was inspired by the English countryside. His few works include a song cycle and orchestral rhapsody based on Housman's Shropshire Lad and the tone-poem The Banks of Green Willow.

|

|

Cole Porter, 1891–1964. American songwriter.

Unlike many Broadway composers, Porter wrote not only the music but the lyrics for his songs, and these are notable for their wit, clever rhyming, and encyclopedic range of reference. In addition to numerous standalone songs that became standards, he also wrote musicals such as Anything Goes (1934), Kiss Me, Kate (1948), and Can-Can (1953).

|

|

George Gershwin, 1898–1937. American composer.

Born Jacob Gershwine in New York to Jewish emigrants from Eastern Europe, he studied piano and composition, but soon found his vocation as a songwriter, mostly with his elder brother Ira (born 1896). Most of his songs have become crossover standards, as have his orchestral works Rhapsody in Blue (1924) and An American in Paris (1928). Most of his stage works are primarily containers for his songs, but his 1935 opera Porgy and Bess is an exception, a closely-developed study of African-American life.

|

|

Aaron Copland, 1900–1990. American composer.

Trained in Paris, Copland began writing in the style of the European avant garde, but in his ballet commissions in the 1930s and 1940s, such as Billy the Kid, Rodeo, and Appalachian Spring, he developed the open folk-inflected style that has become, for many people, the sound of American music.

|

|

Fela Sowande, 1905–87. Nigerian composer.

Recognized as the leading voice in Nigerian "classical" music, Sowande went to London in 1934 to study European music and went on to hold important posts as both performer and scholar. He returned to Nigeria in 1952, then moved to Howard University in Washington in 1962. All this time, he maintained a popular career as a performer, for instance as a duet partner with Fats Waller, band leader, and Hammond organist.

|