• About the Instructor • Return to Index

12 classes

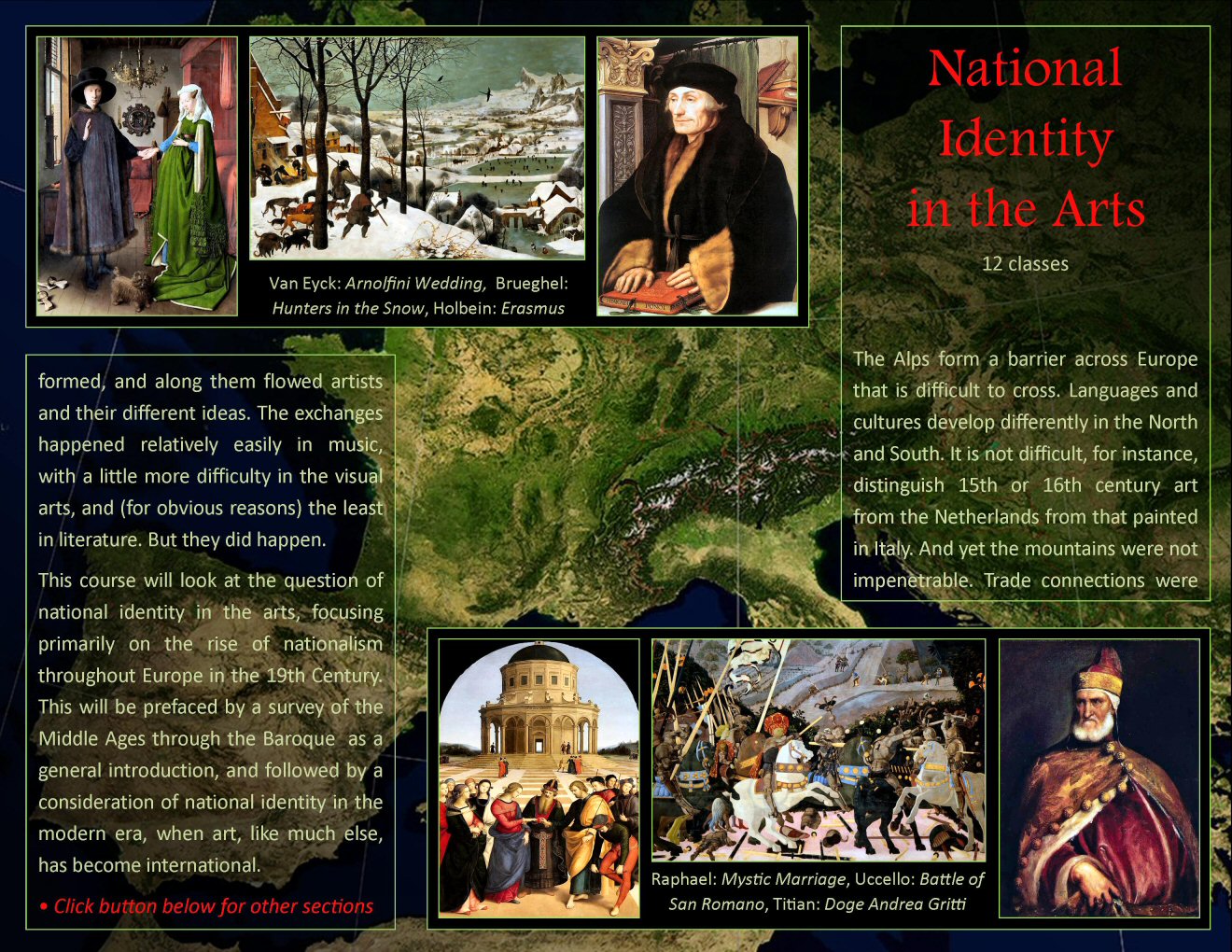

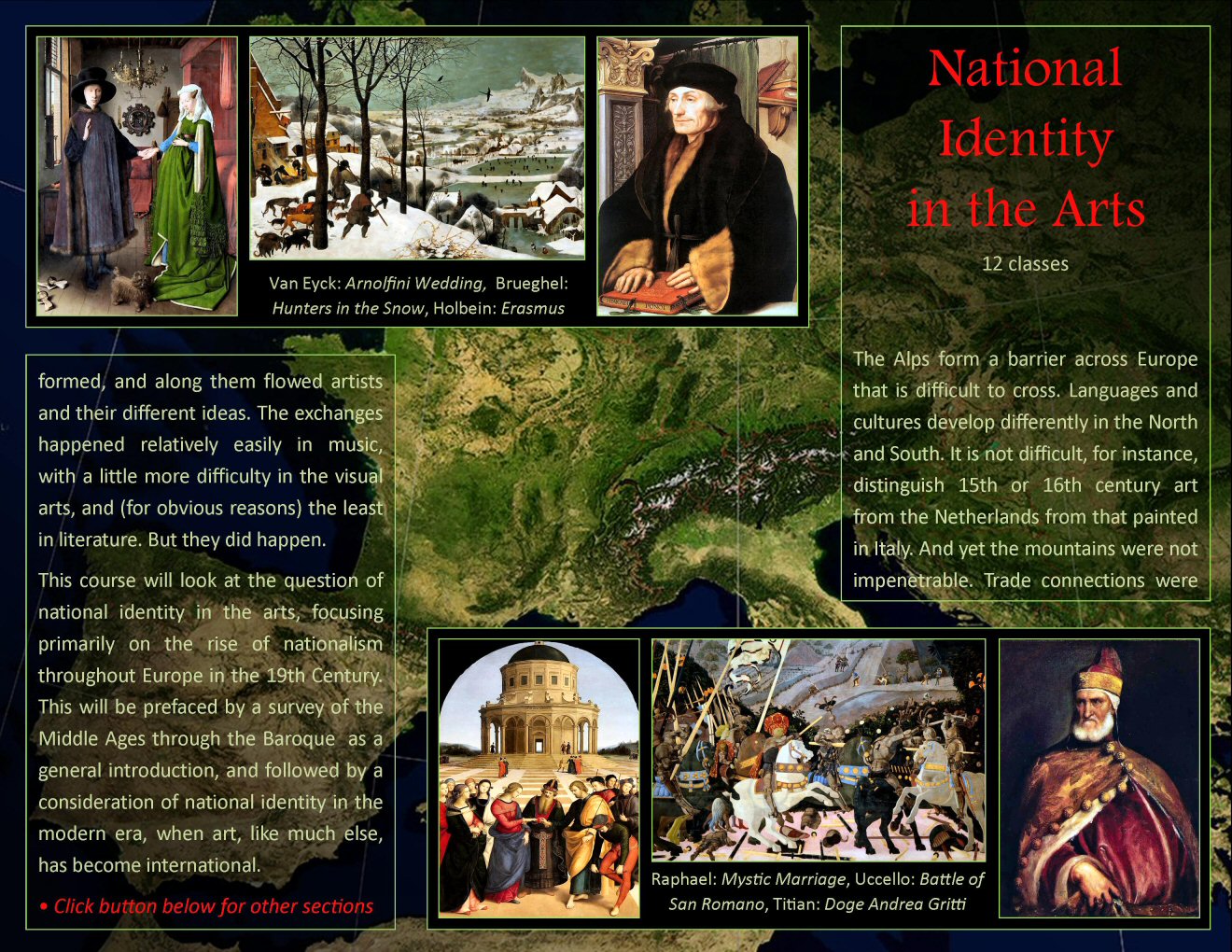

The Alps form a barrier across Europe that is difficult to cross. Languages and cultures develop differently in the North and South. It is not difficult, for instance, distinguish 15th or 16th century art from the Netherlands from that painted in Italy. And yet the mountains were not impenetrable. Trade connections were formed, and along them flowed artists and their different ideas. The exchanges happened relatively easily in music, with a little more difficulty in the visual arts, and (for obvious reasons) the least in literature. But they did happen.

This course will look at the question of national identity in the arts, focusing primarily on the rise of nationalism throughout Europe in the 19th Century. This will be prefaced by a survey of the Middle Ages through the Baroque as a general introduction, and followed by a consideration of national identity in the modern era, when art, like much else, has become international.

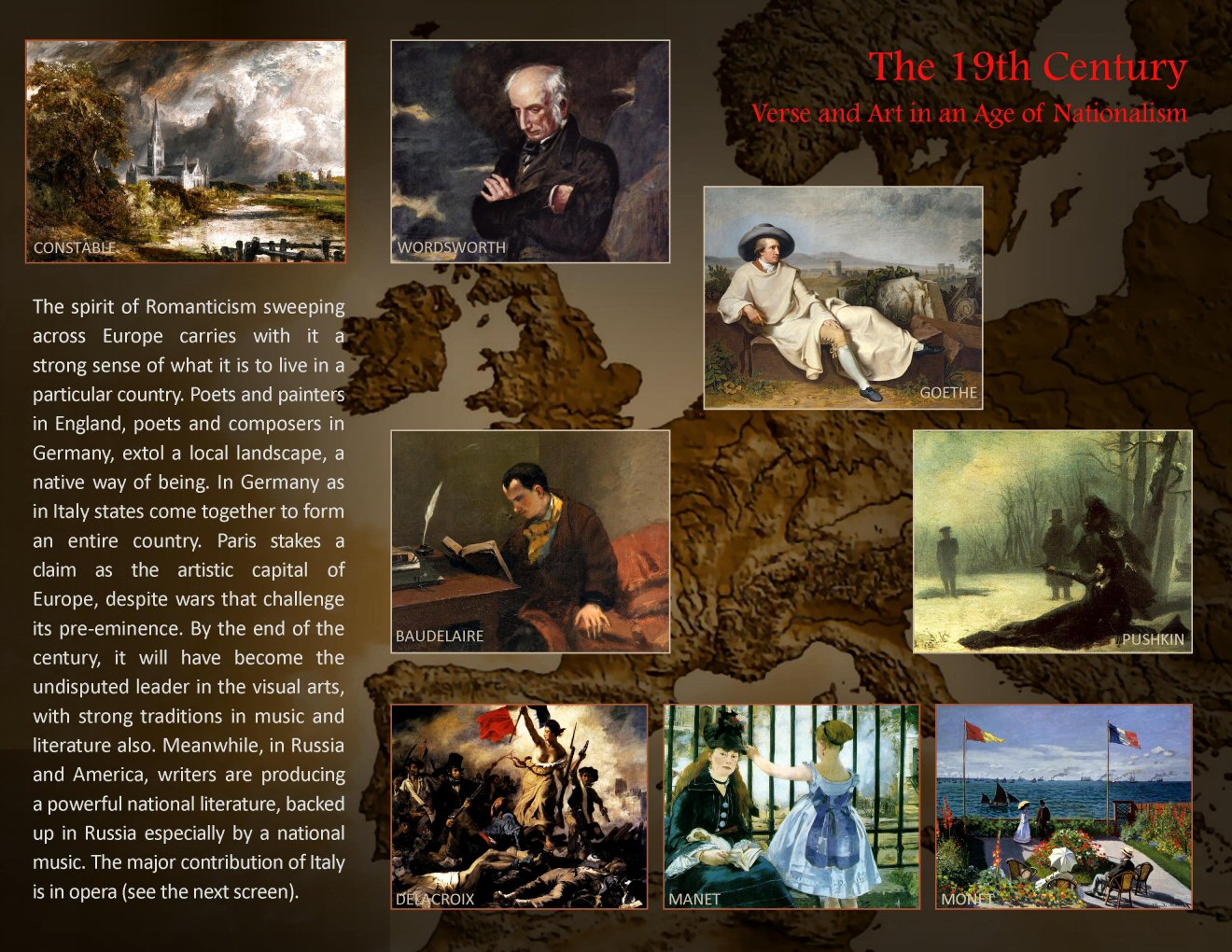

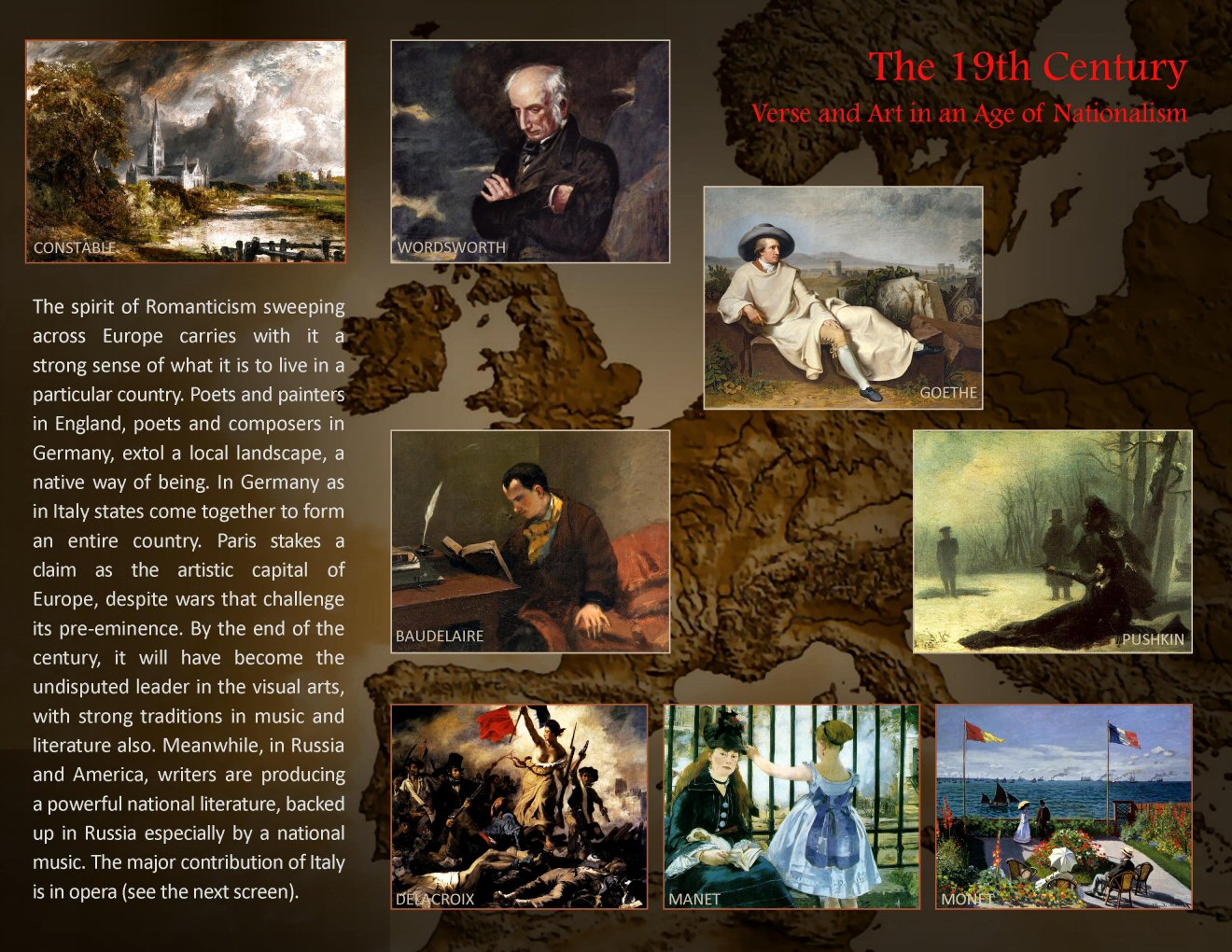

The spirit of Romanticism sweeping across Europe carries with it a strong sense of what it is to live in a particular country. Poets and painters in England, poets and composers in Germany, extol a local landscape, a native way of being. In Germany as in Italy states come together to form an entire country. Paris stakes a claim as the artistic capital of Europe, despite wars that challenge its pre-eminence. By the end of the century, it will have become the undisputed leader in the visual arts, with strong traditions in music and literature also. Meanwhile, in Russia and America, writers are producing a powerful national literature, backed up in Russia especially by a national music. The major contribution of Italy is in opera (see the next screen).

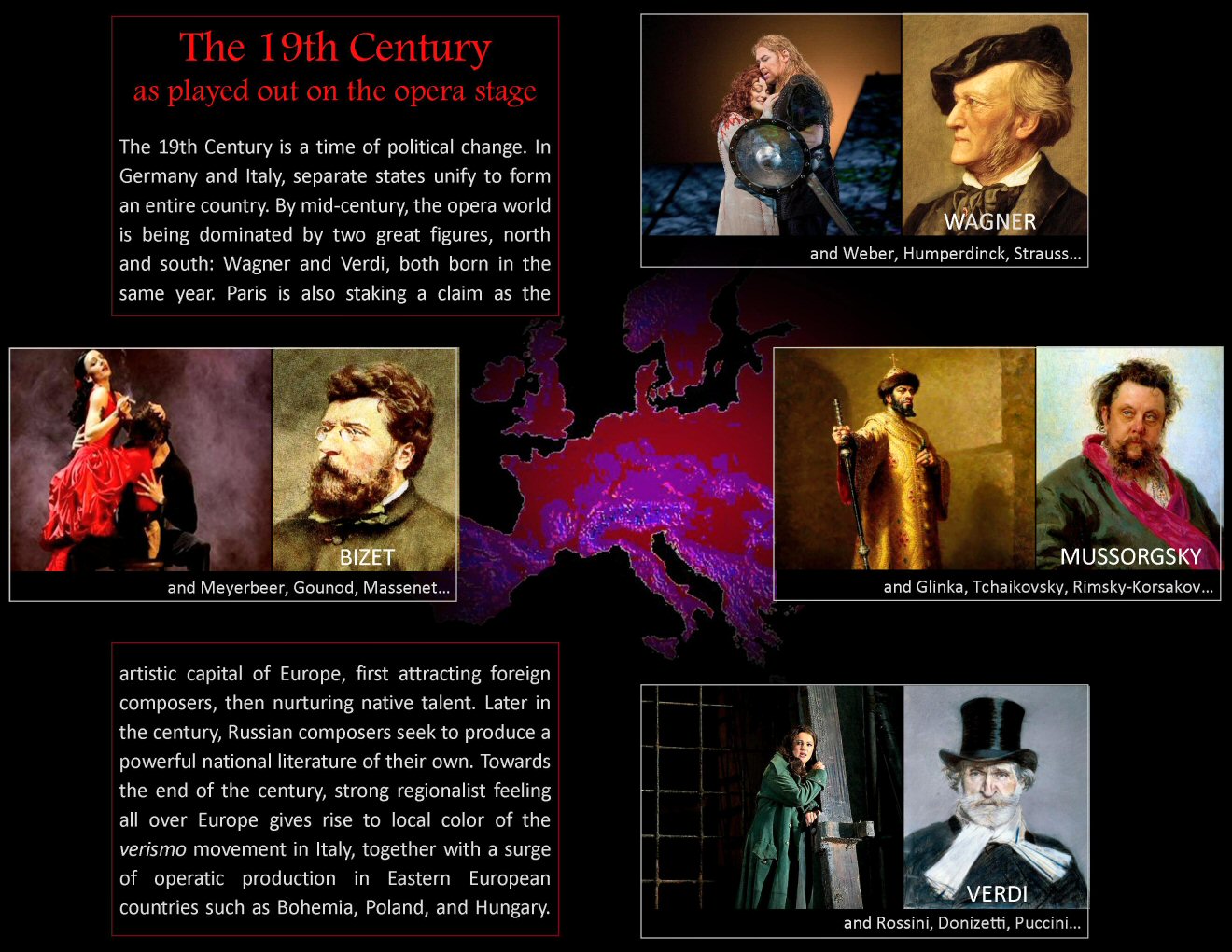

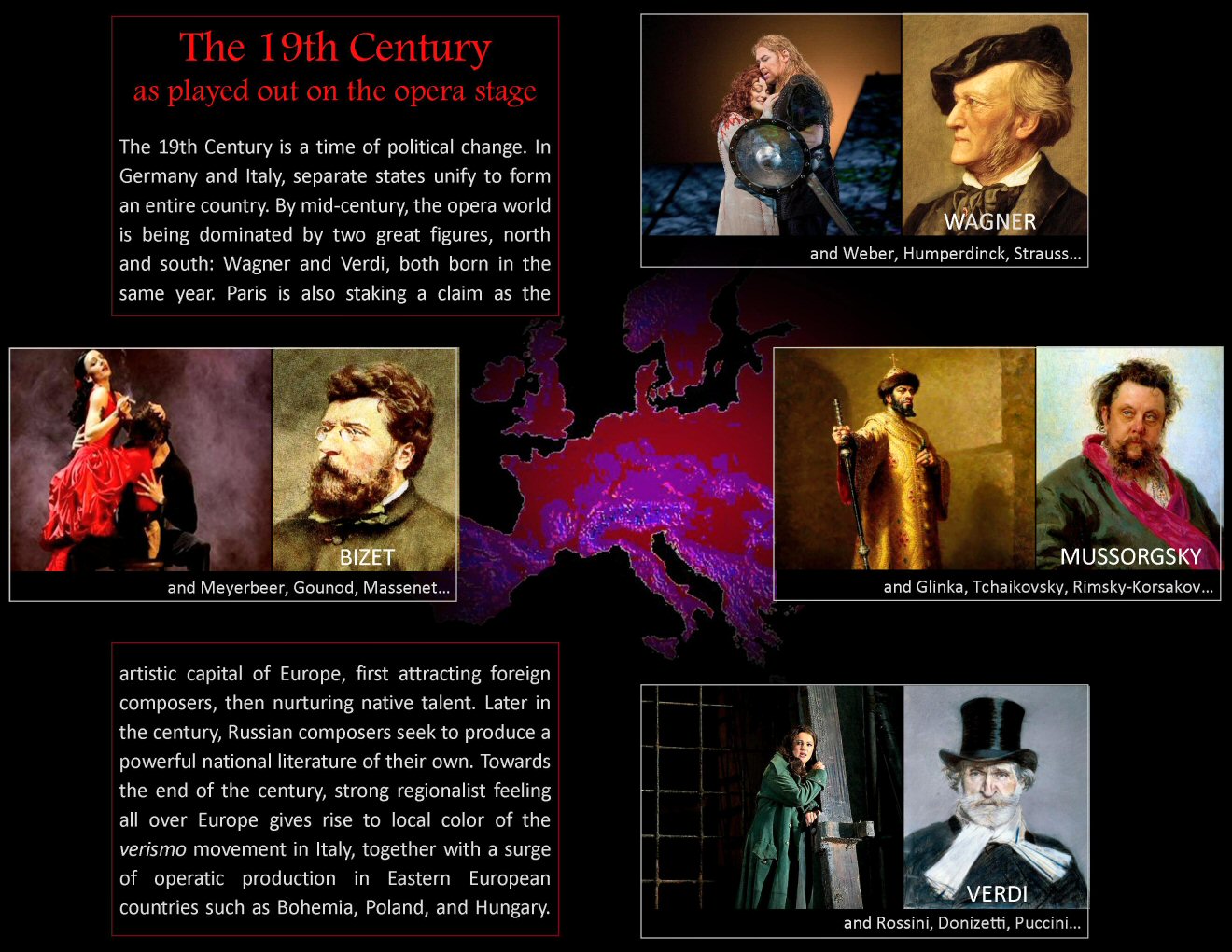

The 19th Century is a time of political change. In Germany and Italy, separate states unify to form an entire country. By mid-century, the opera world is being dominated by two great figures, north and south: Wagner and Verdi, both born in the same year. Paris is also staking a claim as the artistic capital of Europe, first attracting foreign composers, then nurturing native talent. Later in the century, Russian composers seek to produce a powerful national literature of their own. Towards the end of the century, strong regionalist feeling all over Europe gives rise to local color of the verismo movement in Italy, together with a surge of operatic production in Eastern European countries such as Bohemia, Poland, and Hungary. and Czechoslovakia.

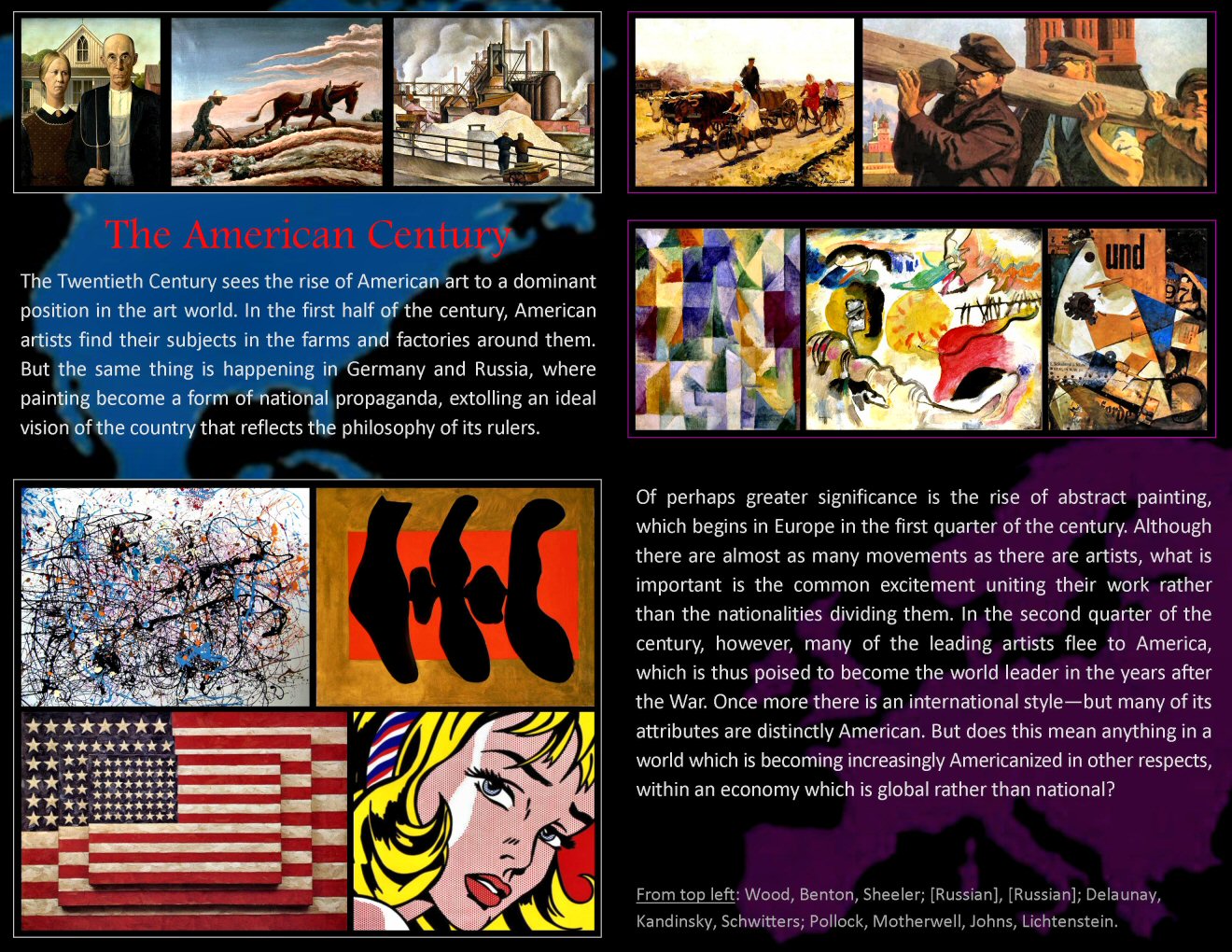

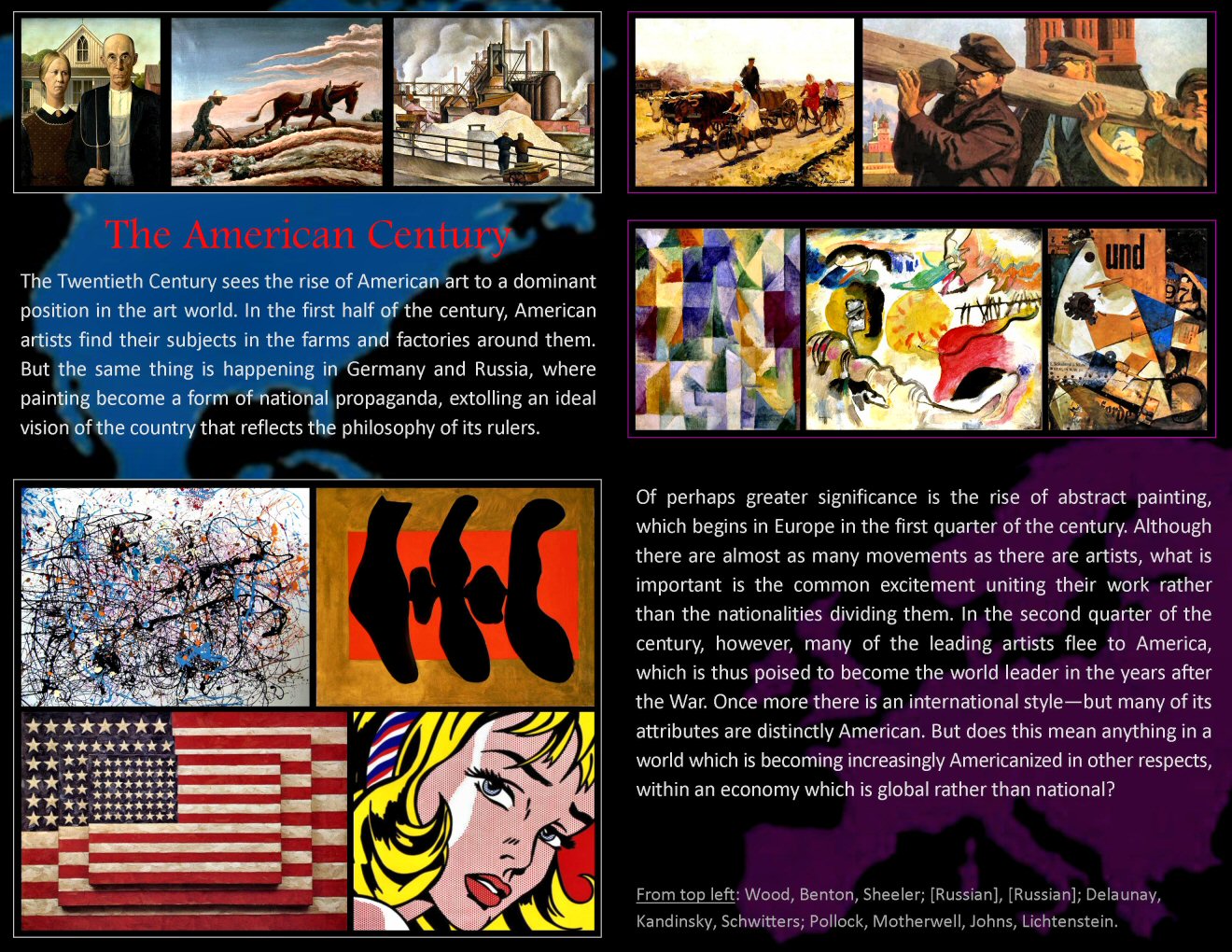

The Twentieth Century sees the rise of American art to a dominant position in the art world. In the first half of the century, American artists find their subjects in the farms and factories around them. But the same thing is happening in Germany and Russia, where painting become a form of national propaganda, extolling an ideal vision of the country that reflects the philosophy of its rulers.

Of perhaps greater significance is the rise of abstract painting, which begins in Europe in the first quarter of the century. Although there are almost as many movements as there are artists, what is important is the common excitement uniting their work rather than the nationalities dividing them. In the second quarter of the century, however, many of the leading artists flee to America, which is thus poised to become the world leader in the years after the War. Once more there is an international style—but many of its attributes are distinctly American. But does this mean anything in a world which is becoming increasingly Americanized in other respects, within an economy which is global rather than national?