• Columbia website, Fall 2020 • About the Instructor • Return to Index

12 classes

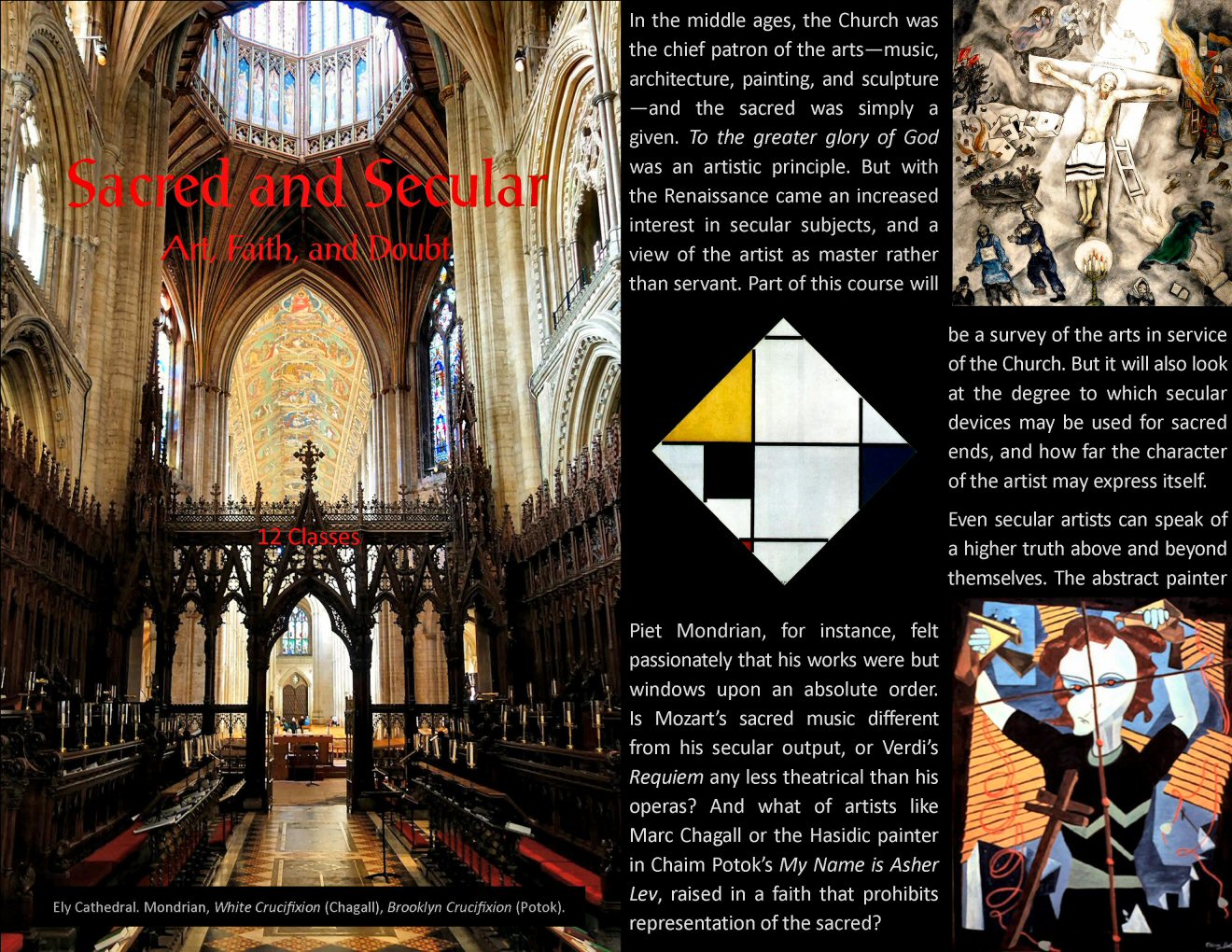

In the middle ages, the Church was the chief patron of the artsómusic, architecture, painting, and sculpture óand the sacred was simply a given. To the greater glory of God was an artistic principle. But with the Renaissance came an increased interest in secular subjects, and a view of the artist as master rather than servant. Part of this course will be a survey of the arts in service of the Church. But it will also look at the degree to which secular devices may be used for sacred ends, and how far the character of the artist may express itself.

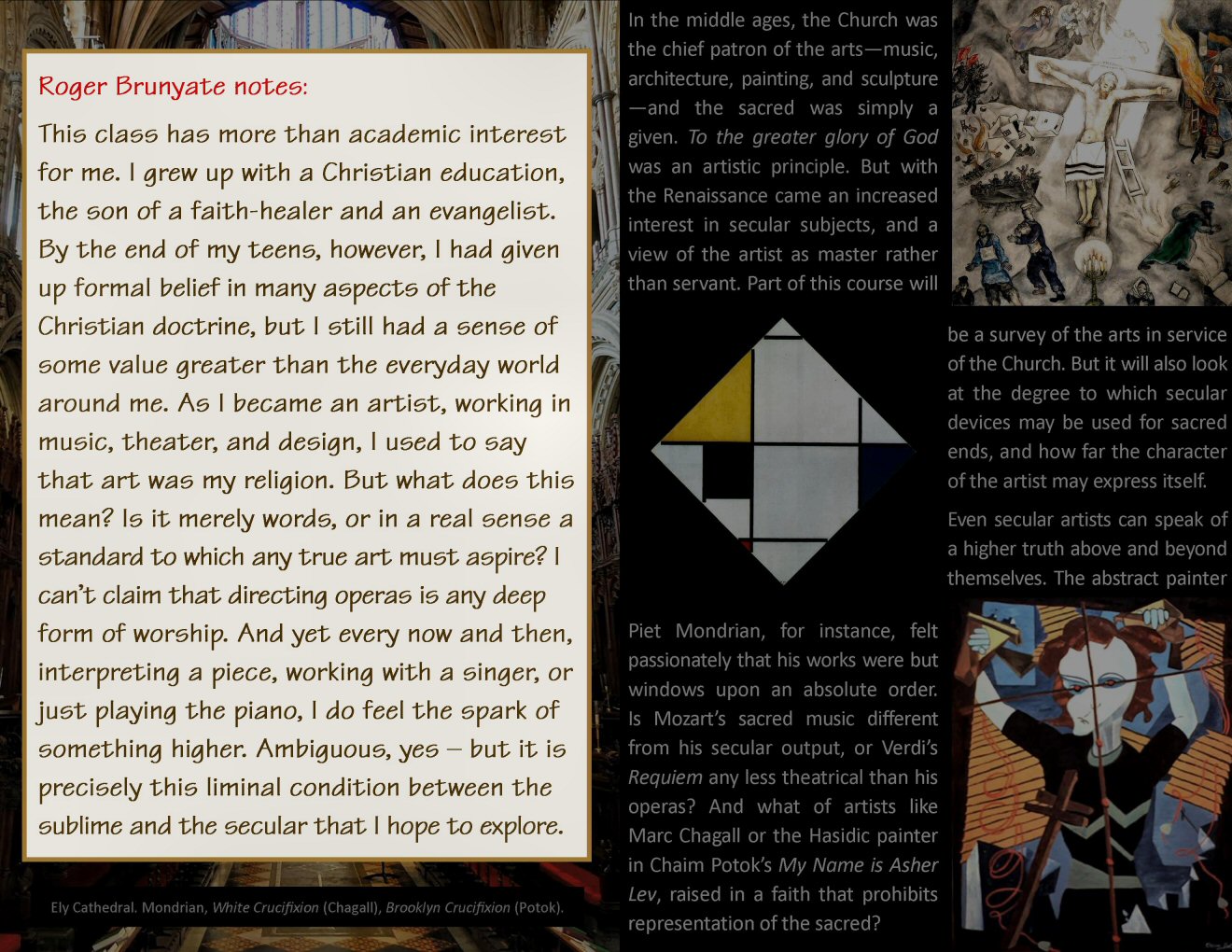

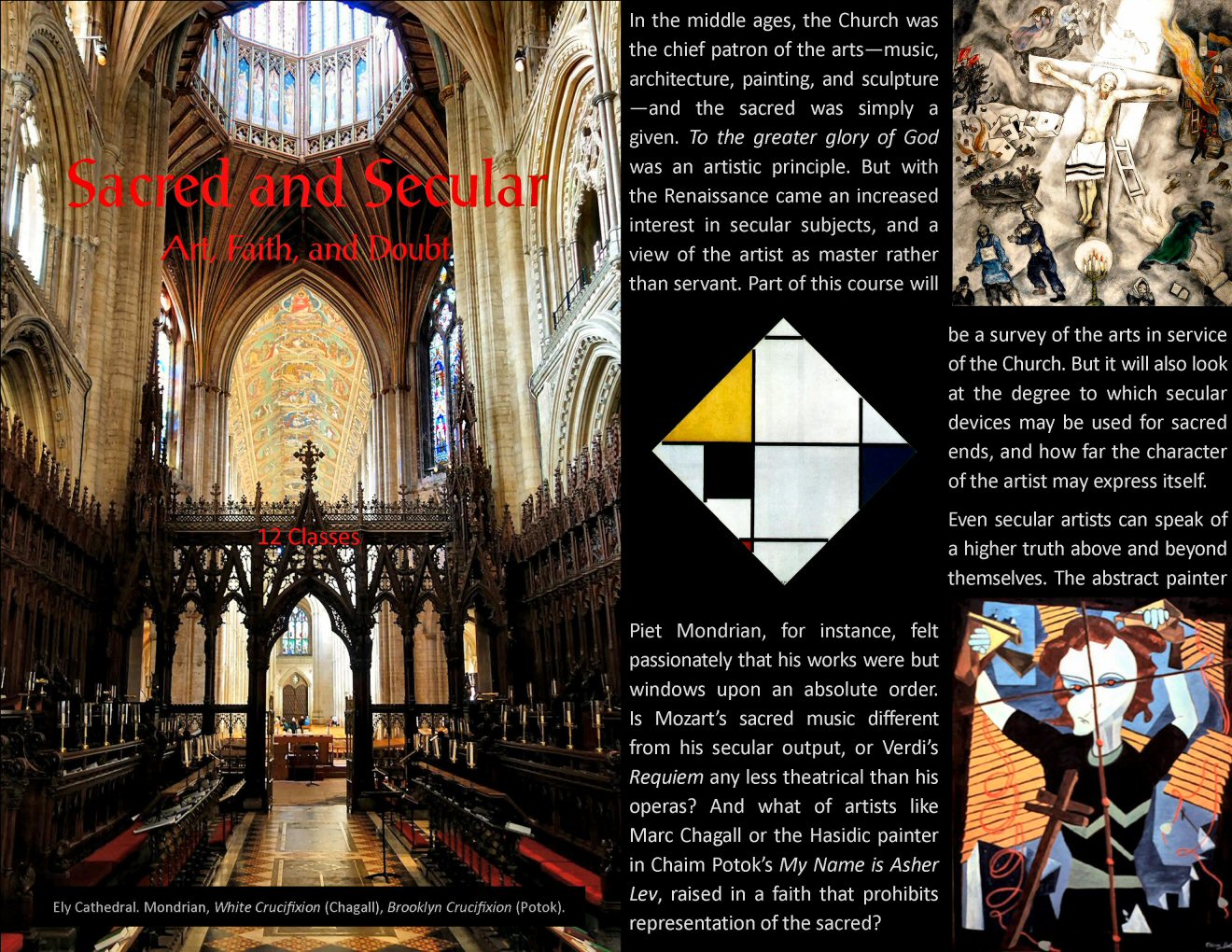

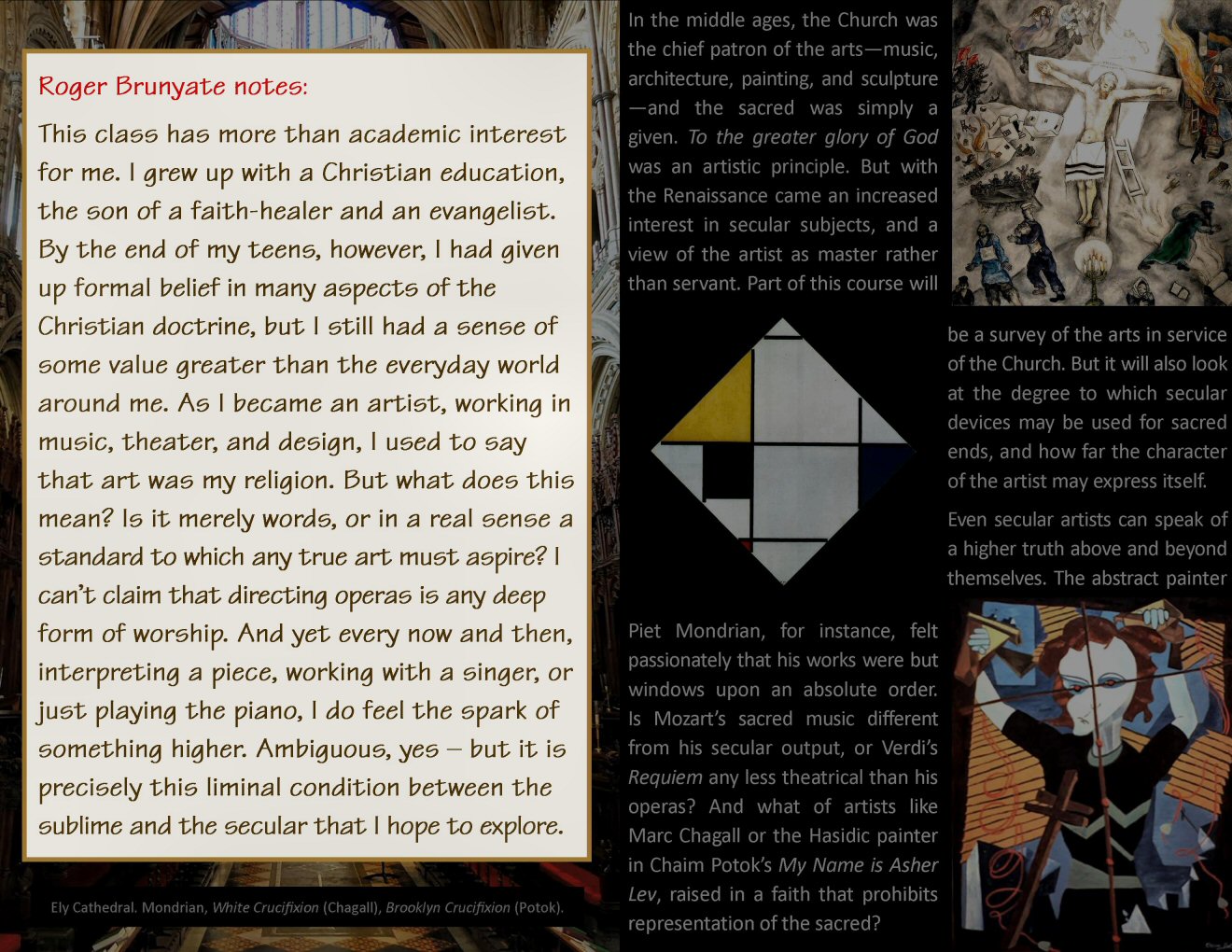

Even secular artists can speak of a higher truth above and beyond themselves. The abstract painter Piet Mondrian, for instance, felt passionately that his works were but windows upon an absolute order. Is Mozartís sacred music different from his secular output, or Verdiís Requiem any less theatrical than his operas? And what of artists like Marc Chagall or the Hasidic painter in Chaim Potokís My Name is Asher Lev, raised in a faith that prohibits representation of the sacred?