2. The Sacred in Music and Text.

The class will survey of some of the ways in which religious poetry has generated accompanying music for more than a

milennium. We will listen to music written to carry texts that form part of the liturgy in Christianity, Judaism, and

Islam. We will also hear works on religious themes conceived for performance in the concert hall. We sum it up with

four creative artists (poets and composers) who, over a span of five centuries, have tried to come to terms with the

awesome scale and intensity of the religious vision.

There is no separate text compilation in this case, as the regular handout contains the two poems to be looked at in

detail. As usual, the full script, videos, and images will be posted immediately after class.

Q AND A

I often have a section here where I can pick up on points I could not answer in class but have thought about since. The

questions below are probably a travesty of what people said, in class or after, but they are useful as a cue to some

of the issues I took away from this morning.

Would it make any difference if the men singing the Palestrina were all dressed the same?

Musically, no. But it would be a step closer to the original liturgical purpose of this music. As someone who has worked

with singers for half a century, I am fascinated by the contrast of ordinary people making extraordinary sounds; for this

reason, I generally prefer live performances to canned ones. But by the same token, I realize that any emphasis on

performance, or many of the other techniques I use to make the clips more interesting to a class, by shifting the

proportions of the consistent media, may actually run counter to the original purpose of much of this sacred music.

Before there was poetry or music was there some universal language (mathematics,

perhaps?) associated with religious expression but not specific to a particular context?

I’m not sure I’ve got this question right; it is way beyond my expertise anyway. But there is one thing I might say from

observation, and that concerns tempo. Think of how people speak: slow or fast, but all within a normal range of

intelligibility. But much religious ritual seems to slow this way down. And very occasionally you get ritual expression,

especially when involving dancing, that is much faster than normal. In short, it seems to me that sacred expression seeks

a different relationship to time (suspended, for example, or ecstatic) from the pragmatic one used in verbal expression.

And if I am right, that would be cross-cultural.

Does it matter how beautifully a cantor sings?

Again, this is outside my expertise. I think we can agree on the negative: that a treatment of the sacred text that did

not treat it with respect would be an abomination. And there might be a mundane factor too: a congregation with a

mellifluous cantor might get a larger and more faithful attendance. But other than that, I’d say no. I know, for example,

that a sacrament in the Catholic church (such as the Mass or ABsolution) performed by a properly-ordained priest is

still valid, even if the priest himself is in a state of sin. By analogy, I would expect that the musicality and vocal

talent of a cantor or rabbi would not affect how they execute their office.

VIDEO LINKS

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Medieval: "Dies Irae"

9th-century chant

|

Verdi: Requiem

Opening of Dies Irae

Riccardo Chailly with La Scala orchestra and chorus |

|

|

|

|

The Book of Esther

Megillah reading (didactic)

|

The Book of Esther

Megillah reading (as worship)

|

|

|

|

|

Quran

Chant by Khalid Al Jaleel |

Psalm 23

Anglican chant

Sung by the choir of King's College Chapel, Cambridge |

|

|

|

|

Psalm 23

Scottish metrical version

Funeral of Queen Elizabeth II at Westminster Abbey |

Gaelic psalm singing

BBC documentary from Back Church, Isle of Lewis, Scotland |

|

|

|

|

Purcell: "Expostulation of the Blessed Virgin"

Christine Brandes with Nicholas McGegan, organ |

Pergolesi: Salve Regina

"Et Jesum benedictum"

Sophie Daneman (audio only, but exquisite!) |

|

|

|

|

Palestrina: Missa Papae Marcelli

Opening (Kyrie)

New York Polyphony |

Runestad: "Let my love be heard"

Bob Cole Conservatory Chamber Choir |

|

|

|

|

Ockeghem: Deo Gratias

36-voice canon (Huelgas Ensemble)

with Memling Last Judgment, as played in class |

Ockeghem: Deo Gratias

36-voice canon (Hilliard Ensemble)

in a version more clearly showing the structure |

|

|

|

|

Donne: Last Judgment sonnet

with Rubens Angel Concert, as played in class |

Gerard Manley Hopkins: God's Grandeur

Reading by King Charles III (as Prince of Wales)

|

|

|

|

|

Reich: Tehillim

Opening

Colin Currie Group, Amsterdam 2015 |

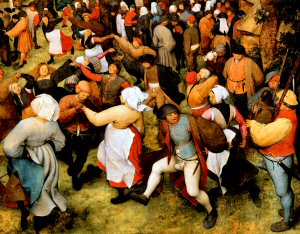

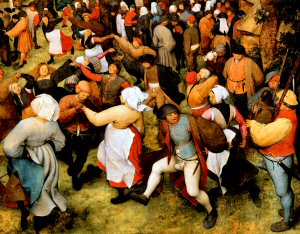

IMAGES

The thumbnails below cover the slides shown in class. Click the

thumbnail to see a larger image.

Click on the right or left of the larger picture to go forward or back,

or outside it to close. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

Johannes Ockeghem, 1430–1497. Franco-Flemish composer.

Writing both sacred and secular vocal music, he was one of the leading musicians of the late 15th century.

|

|

Hans Memling, 1430–94. Netherlandish painter.

Based in Bruges, and probably a pupil of Rogier van der Weyden, he developed a sweeter more balanced version of his style which brought him great success. Also spelled "Memlinc."

|

|

Mathis Grünewald, 1475–1528. German painter.

After painting his extraordinary masterpiece, the multi-paneled Isenheim Altarpiece, in 1515, he faded from memory; his rediscovery as the most visionary artist of his era is fairly recent. "Grünewald" (Greenwood) is a nickname; his real name was Gothardt or Neithardt.

|

|

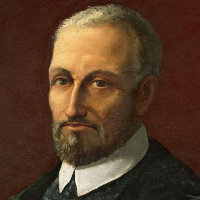

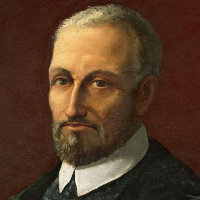

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, 1525–94. Italian composer.

Born near Rome, he was active in Roman churches almost all his life, first as chorister and then as choirmaster. His large output was mainly of sacred music (for example, 105 masses) though he also wrote secular madrigals. His multi-voice contrapuntal style is considered the culmination of renaissance polyphony.

|

|

John Donne, 1572–1631. English poet and cleric.

Though classed with the Metaphysical Poets of the early 17th century, he had an immense range, from erotic to sacred, characterized by an extraordinary intensity. He took holy orders later in life, and was appointed Dean of St Paul's Cathedral.

|

|

Peter Paul Rubens, 1577–1640. Flemish painter and diplomat.

One of the giants of baroque art, Rubens developed the style of Titian into a powerful rhetoric applied equally to sacred and profane subjects, and exerted enormous influence in Spain, England, and France as well as in his native Flanders, continued in the work of his many pupils. His position at so many courts also made him invaluable as a diplomat.

|

|

Nahum Tate, 1652–1715. English poet.

Tate is best remembered today as the librettist of Purcell's Dido and Aeneas and the author of "While Shepherds Watched their Flocks by Night." But he was one of the major playwrights of his day, and his Lear is one of the most notable attempts to reshape Shakespeare into a form acceptable on the Restoration stage.

|

|

Henry Purcell, 1659–95. English composer.

Not only was Purcell the greatest composer of the Restoration period, writing music for occasions ranging from a royal coronation to an opera to be performed in a girls' school (Dido and Aeneas), he was the last indisputably great English composer for almost three centuries. Among many other qualities, he is renowned for the rhythmic acuity of his settings of English texts.

|

|

Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, 1710–36. Italian composer.

Although he died at the age of 26, Pergolesi had already written several operas, including the comedy La serva padrona, and a variety of religious music, most notably his Stabat Mater. His work is noted for its melodic grace and sweetness. More music is attributed to him than he could possibly have written!

|

|

Giuseppe Verdi, 1813–1901. Italian opera composer.

Verdi's two dozen or more operas (depending on how you count them) make him the leading Italian opera composer of his time and among the two or three greatest opera composers ever. After what he called his "years in the galleys," he hit his stride in the early 1850s with the trio of Rigoletto, Il Trovatore, and La Traviata. He intended Aïda (1870) to be his last work, but was persuaded out of retirement to write his final Shakespearean masterpieces: Otello (1886) and Falstaff (1893).

|

|

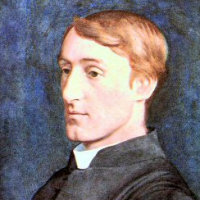

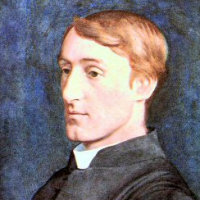

Gerard Manley Hopkins, 1844–89. English poet.

A Jesuit priest, his earlier poetry was concerned with the nature of God as manifested in Nature. Later in his career, he went on to explore the depths of his own soul in bleak depression.

|

|

Alfred Noyes, 1880–1958. English poet.

English schoolchildren know of Noyes from his poem "The Highwayman," but he had a varied career that included six volumes of verse, an epic trilogy The Torch Bearers, a play about Robin Hood, and nine years of teaching at Princeton.

|

|

Steve Reich, 1936– . American composer.

Reich's contribution to the minimalist movement was through his concept of "phase shifting," simple patterns which change perceptibly as one listens. His Music for 18 Musicians (1976) and Tehillim (1981) have become minimalist icons. His Different Trains (1988) for taped voices and string quartet, is a striking musical memorial to victims of the Holocaust.

|

|

Jake Runestad, 1986– . American composer.

As a composition student at the Peabody Conservatory, Runestad wrote in many genres, including opera, but he has gone on to become one of the most successful composers writing for and inspired by the great choral tradition of the American Midwest.

|