3. Songs of the People.

Folk songs may be loosely defined as music that is transmitted orally and has no identifiable composer, often found in

different variants from different places. They may have grown up around anonymous texts, but quite often these

are forgotten and only the melody remains. In the first section of class, we shall look what gives folk song its

distinctive flavor. In the second, we consider different contexts for folk songs and the various purposes they serve.

And in the brief final section, we sample some of the ways in which folk music has invaded the classical venues of opera

house and concert hall.

There is no separate text compilation in this case, as most of the songs have traditional words that differ slightly

between renderings. As usual, the script, videos, and images will be posted immediately after class.

Q AND A

What is "Carrickfergus"?

John Russell mentioned this song; he wrote to me about it later, in an eMail that crossed with my first posting of

this. I did not know "Carrickfergus" the song, even though I saw the town of that name across Belfast Lough every

time I looked out of our windows as a child; you can hear it here. John added this as a straightforward version that also gives the text, and this for "Kevin Rowland’s decidedly modern interpretation," as he puts it. I

was struck by the total avoidance of Irish sentiment in the last of these.

What is the connection between "Carrickfergus" and "The Water is Wide"?

This was John's original question. He quotes AI as saying that, in both words and music, the

two songs are distant variations of the same thing. I myself can hear no more than a faint general similarity

in the music, but there are words in the first verse of "Carrickfergus" ("I would swim over the deepest

ocean / for my love to find / but the sea is wide and I cannot cross over / nor do I have any wings to fly") that

are pretty much identical to "The Water is Wide." Just as "Green grow the rushes, O" appears in more than one folksong,

so I think there are common tropes in folk texts, which you get in quite different contexts. Incidentally, there are

numerous versions of "The Water is Wide" on YouTube; most, including the Britten that I played, are clever

arrangements. The one that comes closest to the unvarnished song, I think, is this lovely audio version of an American variant by Joan Baez.

Do folksongs have to be arranged for performance?

Yes, just about all of them do; even an apparently natual context such as we heard in Twelve Years a Slave

required somebody to notate it, and plan when the different voices would come in, their speed, and so on. The one

song I played that did not seem arranged at all was "Barbara Allen" as sung by Jean Ritchie. For instance, all

three of the songs I played at the start to illustrate folksong flavor were arrangements, so quite apart from my

getting the volume wrong (I know how to do it now), it was actually quite difficult to separate the song from

the work of the arranger.

What is the relationship between text and tune?

This was John again. You may remember that I was surprised to hear him say that the first three songs were

text-dominated, because one of the things I would have said was that while the tunes tended to survive in some

form, the words often changed or got forgotten. But I think he was commenting on the work of the arrangers, as

mentioned above. All three settings had the quality of a musical background against which the voice was heard;

I would prefer to say that they were dominated by the voice rather than the words the voice was singing.

But I see that I am going to have to abandon any hope of generalizing. The music of narrative songs, protest

songs, and spirituals must surely have come about to carry the words, whose meaning is the main point. But with

some other types, such as work songs, the words are virtually unimportant. And even some instructional songs like

"I'll give you one-oh," where you would think the text is essential, survive even when people have forgotten

what half the words are supposed to mean.

VIDEO LINKS

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Loosin Yelav (Armenia)

From Folk Songs by Luciano Berio (1964)

Magdalena Kozena with Sir Simon Rattle |

Gjendine's Lullaby (Norway)

Folksong colllected by Edvard Grieg

Trio Medieval |

|

|

|

|

Green grow the rashes O (Scotland)

Song by Robert Burns, 1784

Performed by The Band of Burns |

Barbara Allen

Traditional, Appalachian version

Sung by Jean Ritchie (audio only) |

|

|

|

|

Barbara Allen

Traditional, British version

Sung by Andreas Scholl (countertenor) |

Green Grow the Rushes, O

Traditional counting song

King Solomon's Singers, Chicago (audio only) |

|

|

|

|

Green Grow the Rushes, O

Counting song on Sesame Street

The song in its teaching role |

Echad Mi Yodea

Passover counting song

Rabbi Ruth Gan Kagan and family

A Hebrew equivalent of the above |

|

|

|

|

Echad Mi Yodea

Dance by Ohad Naharin

Performed by Bathsheva Young Ensemble

Interesting dance version of the above |

The Water is Wide (O waly, waly)

Traditional, arranged by Benjamin Britten

Kathleen Ferrier with the composer |

|

|

|

|

Boney was a warrior

Traditional sea shanty, early 19th century

Sung by Paul Clayton |

Three Shanties for Wind Quintet

Malcolm Arnold (1943)

Movements 2 and 3; members of the San Diego Symphony

Folksong in classical music: lovely slow version of "Boney" |

|

|

|

|

Johnny come down to Hilo

Traditional sea shanty

Sung by the Fisherman's Friends

Song used by Malcolm Arnold in 3rd movement of the above |

Long John

Traditional work song

Sung by a Texas chain gang, 1934 |

|

|

|

|

The Gospel Train

Traditional spiritual, arranged for chorus

Sung by US Navy Sea Chanters (audio only) |

Roll, Jordan, roll

Traditional spiritual

From the movie 12 Years a Slave

Topsy Chapman and Chiwetel Ejiofor |

|

|

|

|

Blowin' in the wind

Song by Bob Dylan (1962)

|

Where have all the flowers gone?

Joan Baez performing 1955 song by Pete Seeger

with posters by Sister Corita Kent (own video) |

|

|

|

|

The Beggar's Opera, 1728

Two choruses from the Ballad opera by John Gay

Film by Peter Brook, 1953 |

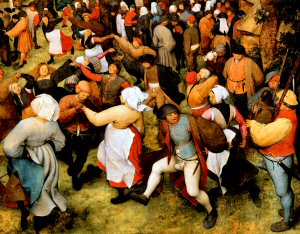

Eugene Onegin

Opera by Tchaikowsky (1879); chorus from Act I

Film by Petr Weigl, 1988

Folk music used in romantic opera for local color |

|

|

|

|

Jenufa

Opera by Janacek (1904); chorus from Act I

Liceu, Barcelona: Par Lindskog Stárek (Steva)

Folk music used in C20 opera for local color |

A Somerset Rhapsody

Gustav Holst (1907), "High Germany" section

Band arrangement by Sam Vanderwoude,

who plays all the parts! |

|

|

|

|

Folk Songs from Somerset

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1923), excerpt

Orchestra of St. Martins in the Fields,

conducted by Sir Neville Marriner (own video) |

Mañanita de San Juan

From Ayre by Osaldo Golijov (2004)

Sung by Ilana Davidson

Conceived as a companion piece to the Berio (below),

this presents folk music from diverse Mediterranean cultures |

|

|

|

|

Azerbaijani Love Song

From Folk Songs by Luciano Berio (1964)

Cathy Berberian, with the composer |

IMAGES

The thumbnails below cover the slides shown in class. Click the

thumbnail to see a larger image.

Click on the right or left of the larger picture to go forward or back,

or outside it to close. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

Johann Pepusch, 1667–1752. German-born British musician.

Johann Christian Pepusch grew up in Berlin. When still in his teens, he took up a position at the Prussian court, where his pupils included the future Frederick the Great. In 1698, he moved to Amsterdam and thence to London, where he led a long career as a teacher, conductor, and theater musician, in which capacity, he arranged the music for John Gay's Beggar's Opera (1728).

|

|

John Gay, 1684–1732. English poet and playwright.

Although he wrote the libretto for Handel's early opera Acis and Galatea (1718), Gay is best known as the author of The Beggar's Opera (1728), satirizing the very kind of opera that Handel made famous. The songs in this piece about highwaymen and whores are sung to popular tunes arranged by the German-English composer Johann Pepusch.

|

|

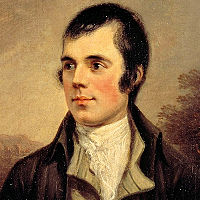

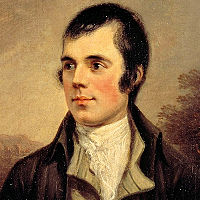

Robert Burns, 1759–96. Scottish poet.

Rabbie Burns is often regarded as the national poet of Scotland, where his birthday (1/25) is an occasion for the often-drunken singing of his many songs. His manner as "peasant-poet" was largely assumed; he was in fact quite well educated, and held his own with other figures of the Scottish Enlightenment. He wrote mainly in a Scottish dialect, but it is mostly intelligible to non-Scots.

|

|

Cecil Sharp, 1859–1924. English folksong collector.

Sharp was the pre-eminent figure in the English folk-song revival in the early 20th century, collecting over 4,000 songs from untutored singers in SW England and the Appalachian Mountains in the US. Although he was also a composer, his more important musical legacy can be found in the inspiration he gave to other composers, such as Vaughan WIlliams, Holst, and Butterworth.

|

|

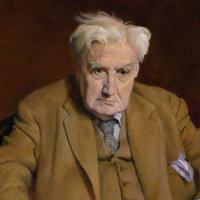

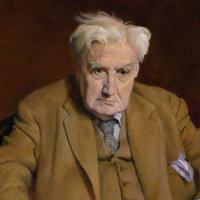

Ralph Vaughan Williams, 1872–1958. English composer.

Associated with the English folk song revival, he was more than anybody responsible for giving English music its national voice. He wrote nine symphonies and numerous vocal works, including the one-act opera Riders to the Sea. His first name is pronounced "Rafe."

|

|

Gustav Holst, 1874–1934. English composer.

The son of a church organist of Swedish descent, Holst studied first the piano and then the trombone. With Ralph Vaughan Williams, he was largely responsible for the revival of interest in English folk music at the turn of the century. He worked most of his life as a church musician and in education, but wrote numerous works, of which The Planets (1918) is the largest and most famous.

|

|

Benjamin Britten, 1913–76. English composer.

Arguably the leading opera composer of the mid-20th century, Britten's major operas have included Peter Grimes (1945), Billy Budd (1951), Gloriana (1953), A Midsummer Night's Dream (1960), and Death in Venice (1973), plus many stage works for smaller forces. He was equally active as a composer of instrumental music and text settings, and latterly as a conductor and accompanist.

|

|

Corita Kent, 1918–86. American artist.

Born in Iowa, Frances Elizabeth Kent entered the Californian Sisters of the Immaculate Heart at age 18, and took the name Sister Mary Corita. The order was known for its liberalism and respect for creativity, and Sister Corita flourished, teaching herself silk-screen printing and eventually becoming head of the college art department. But her increasing social activism set her at odds with her Cardinal, and she left the order in 1968 to continue her work on the East Coast under the name Corita Kent.

|

|

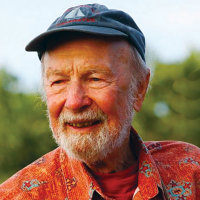

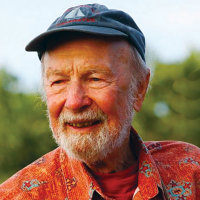

Pete Seeger, 1919–2014. American folk musician.

The son of musicians, Seeger first established himself in the classical world, for example by setting up the music department at UC Berkeley. But forced to resign in 1918 due to his outspoken pacifism, he gradually turned to folk music, emerging after WW2 as a prominent proponent of protest songs including "Where have all the flowers gone?" and "We shall overcome."

|

|

Luciano Berio, 1925–2003. Italian composer.

After following a practice of strict serialism for some years, Berio began to depart from it by including elements of chance and collage, incorporating fragments of other works as in his Sinfonia (1969), arguably his masterpiece. His Folk Songs of 1975 was one of several works written for his wife, the American soprano Cathy Berberian.

|

|

Bob Dylan, 1941– . American singer-songwriter, author, and artist.

His songs of the 1960's such as "Blowin' in the Wind" became anthems of the Civil Rights movement, but he has continued writing in many genres ever since. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2016.

|