3. Aiming at Eternity.

"Architecture has its Political Use; publick buildings being the Ornament of a Country; it establishes

a Nation, draws People and Commerce; makes the People love their native Country, which Passion is the

Original of all great Actions in a Commonwealth. Architecture aims at Eternity." So wrote Sir

Christopher Wren. He was talking, of course, of the great public buildings of government or the church,

which together project an image of how a country wants its citizens to see it. This was obviously a major

concern in post-revolution America. It also became one in Britain after the Houses of Parliament burned

down in 1834.

For the most part, 19th-century architecture recycled old styles, with a fierce battle between Classical

and Gothic. But there were exceptions from mid-century on, when new purposes or new materials demanded

their own solutions. And by separating style from content, those battles had an unexpected consequence:

follies and fancies in both countries where style itself was the subject, to be pursued with exuberance

and even wit. rb.

The script, videos, and images will be posted immediately after class.

TO THINK ABOUT

The two structures below will not be discussed in class, but some of their implications will. They are about 35 years

apart, but both serve the same function, as entrance gates to a large enclosed area. Think about them; click to see the

images at larger size, then click the links below for some suggested questions to consider; click again for partial

answers.

Here are brief bios of the major artists considered in the class, listed in order of birth.

An alphabetical listing of artists for the whole course can be found at the

BIOS link on the syllabus page.

|

Christopher Wren, 1632–1723. English architect.

Sir Christopher Wren was a mathematician, physicist, and astronomer before devoting himself full-time to architecture; he was a founder of the Royal Society, and for two years its president. The biggest boost to his career was the commission to rebuild 54 London churches after the Great Fire of 1666—among them his masterpiece, St. Paul's Cathedral.

|

|

William Kent, 1685–1748. English architect.

Kent was painter to the royal court, but his chief talent was as an architect, responsible for introducing the Palladian style to England, and as a landscape designer, essentially creating the characteristic English country park at Chiswick, Stowe, and elsewhere.

|

|

John Nash, 1752–1835. English architect.

The leading architect of the Georgian and Regency periods, Nash was largely responsible for establishing the classical face of London, with Regent Street, the Regent's Park terraces, Buckingham Palace, and Marble Arch. He also designed several buildings in non-classical picturesque styles, most notably the Indian-inspired Royal Pavilion at Brighton.

|

|

Pierre Charles L’Enfant, 1754–1825. French engineer.

Born in Paris, L'Enfant was recruited by the French playwright Beaumarchais to serve in the American Continental Army, where he became military engineer to George Washington, who later commissioned him to draw up plans for the new capital city bearing his name. Although he did not personally supervise most details of its execution, his plan is very largely still in place today.

|

|

William Thornton, 1759–1828. American architect.

Born in the West Indes on a sugar plantation owned by his parents, Thornton returned to England for his schooling and eventually qualified as a physician. He emigrated to America in 1786, and began to explore other interests, including efforts to expiate his family's role in slavery. He won the competition for the design of the new US Capitol, and it is for that he is now best remembered.

|

|

William Beckford, 1760–1844. English writer.

Author, designer, Member of Parliament, reputedly the richest commoner in England (through the slave trade), and a certified eccentric, Beckford built the huge Gothic extravaganza Fonthill Abbey, a suitable background for his 1786 novel Vathek. It soon collapsed, but it put Gothic on the cultural map.

|

|

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, 1764–1820. British architect.

Latrobe emigrated to the United States in 1796. His works, all in a neoclassical style, include the US Capitol and the Baltimore Basilica.

|

|

Charles Barry, 1795–1860. English architect.

Barry's first commissions as an architect were for churches in the Gothic style, but his later buildings mostly used the classical style of the Italian palazzo as the basis for city buildings and country houses. The two styles met in his designs for the Houses of Parliament which, as his collaborator Augustus Pugin remarked, put "Tudor details on a classic body."

|

|

Joseph Paxton, 1803–69. English architect and gardener.

Paxton faked his age as a teenager to obtain employment as an under-gardener at Kew. His energy impressed the Duke of Devonshire, who made him his head gardener at Chatsworth at the age of 20. There, among other things, he developed the cultivar of banana most commonly eatern today, and built a revolutionary greenhouse to house it. Such experiences put him in a position to propose a giant glasshouse for the Great Exhibition in 1851—the Crystal Palace—which in turn catapulted him to a career in more conventional architecture.

|

|

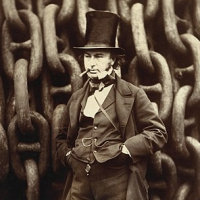

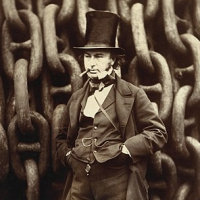

Isambard Kingdom Brunel, 1806–59. English engineer.

Brunel is credited with altering the face of England more than any other engineer of the Industrial Revolution, creating railroads, tunnels, bridges, stations, and the first transatlantic steamer. Among his most notable works are the Clifton Suspension Bridge and Paddington Station.

|

|

Augustus Welby Pugin, 1812–52. English architect.

A convert to Catholicism, Pugin was an evangelist for the moral authority of the Gothic style, as representing an age of piety and communal support, ideas he put forward in his 1836 book Contrasts, setting his vision of an idealized 15th century against the sterility of his own time. He was responsible for all the detail in Charles Barry's rebuilt Houses of Parliament.

|

|

William Butterfield, 1814–1900. English architect.

Butterfield's church of All Souls, Margaret Street, London (1850) established him as the chief architect of the high-church Oxford Movement, to which he responded by creating his own style of historically eclectic High Gothic. In his later buildings such as the chapels at Keble College Oxford and Rugby School, he used Sienese-inspired stripes of polychrome stone, facetiously dubbed the "holy zebra style."

|

|

James Renwick Jr., 1818–95. American architect.

Renwick was trained as an engineer, but pivoted to architecture, a subject he had studied by observation in Europe but was never formally taught. He won the competition for the original Smithsonian Building in 1846, and its Gothic-influenced design helped launch the Gothic Revival in America, including his own St. Patrick's Cathedral in NYC (1858).

|

|

William Powell Frith, 1819–1909. English painter.

Frith began his career as a portrait painter (his subjects including Charles Dickens), but branched out to literary and genre subjects and the vast panoramas of contemporary life such as Derby Day and Railway Station that became his best-known legacy.

|

|

Francis Fowke, 1823–65. Irish engineer and architect.

A military enineer by profession, Fowke goes down in history as the primary designer of two iconic landmarks of Victorian South Kensington: the Natural History Museum (1864) and Royal Albert Hall (1867). His early death, however, meant that these were both taken over by other architects: Alfred Waterhouse and Henry Scott.

|

|

Alfred Waterhouse, 1830–1905. English architect.

Waterhouse was the most succesful late Victorian architect, responsible for huge projects such as the Manchester Town Hall (1866), the Museum of Natural History (1873), and numerous collegiate buildings at Oxford, Cambridge, and several of the new universities.

|

|

Philip Webb, 1831–1915. English architect.

Webb was the principal architect of the English Arts and Crafts movement, advocating traditional materials and design. He worked with Burne-Jones, the two Rossettis, and William Morris, for whom he built the Red House in Bexleyheath, a virtual manifesto of their shared principles.

|

|

William Morris, 1834–96. English designer.

Morris was a textile designer, poet, and social activist, the most prominent figure in the 19th-century Arts and Crafts movement. He preached a return to simplicity, inspiration taken directly from nature, and hand-crafted rather than machine-made objects. All the same, the firm he founded to produce his designs remained a commercial force for over a century.

|

|

Henry Hobson Richardson, 1838–86. American architect.

After studying engineering at Harvard and Tulane, Richardson switched to architecture and moved to Paris to study. He moved to New York in 1865 and struggled to launch a career. This eventually took off in the early 1870s, when he began to experiment with the massive masonry and limited ornamentation of early French medieval architecture, developing the highly original style commonly known as "Richardson Romanesque."

|

|

Aston Webb, 1849–1930. English architect.

The architect of the Victoria and Albert Musuem, Sir Aston Webb may not have been London's most original figure, but his redesign of the Royal Mall, together with Admiralty Arch, Victoria Memorial, and façade of Buckingham Palace have left a lasting stamp on the geography of ceremonial London.

|

|

Louis Sullivan, 1856–1924. American architect.

Sullivan moved to Chicago in 1873 to join building boom following the Great Fire of 1871. After various short residencies to learn his craft, he became the partner of Dankmar Adler in 1880. Together, they designed many theater buildings and commercial blocks that became some of the first skyscrapers. He is credited with the phrase "form follows function," but his own relatively austere forms were illuminated with details that are pure are and nothing to do with function at all.

|

|

Charles Ives, 1874–1954. American composer.

The son of a musician, Ives got a job as an organist at 14 and studied music at Yale. Going into the insurance business (and founding his own successful company), he continued to play and began to compose—pieces which are among the most original of his time, exploring simultaneity, polytonality, and unusual scales.

|