4. Industrial Impacts.

There were two Industrial Revolutions in the 19th Century. The first, which began in Britain, involved the introduction

of machinery, powered first by water and then by coal and steam, to do work that previously had been managed by hand.

This would have a profound effect of the lives of ordinary people. It would also be reflected in the arts: painters

generally viewed these developments in a positive light; poets warned of the danger of losing one's soul; novelists

found ways to span the gap.

Although the Second Industrial Revolution had equivalents in other countries, it was primarily associated with the rise

of America to world status as an economic power. Mainly this was a matter of scale and communication: mass production,

and the linking of mines, steelworks, and factories in vast networks connected by rail, coordinated by recent discoveries

in electricity and telegraphy. It was a period that made a few tycoons very rich, often at the expense of the working

masses; the Gilded Age was by no means golden for everybody.

Because of the immense amount of factual material falling within the purview of this particular class, I have decided to

focus less on the technologies than on their social effects, whether directly or through the vast changes they brought

about in social structure and the distribution of wealth, hence my title "Industrial Impacts." rb.

The script, videos, and images will be posted immediately after class.

TO THINK ABOUT

Two poems by William Blake, both titled The Chimney Sweeper. They were

published two years apart, in Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience. Most similar pairs in

these collections contrast an idealistic view with a harsher one, but that contrast is not so clear here. Unlike

the two paintings below, these poems will be discussed in class.

Two views of large cities, around the end of the Nineteenth Century; neither is by a well-known artist. The London

one (top) was painted in 1880 by John O'Connor (183089). The view of New York dates from between 1900 and

1908 (I have seen both dates), and is by Colin Campbell Cooper (18561937). Neither will be discussed in class,

but both show the results of a century of industrial expansion. Click for enlargements and compare them.

Here are brief bios of the major artists considered in the class, listed in order of birth.

An alphabetical listing of artists for the whole course can be found at the

BIOS link on the syllabus page.

|

Joseph Wright of Derby, 173497. English painter.

A highly original painter, and important precursor of Romanticism, he adapted the candlelight and moonlight genres of Dutch painting to English landscape subjects and scenes relating to the Industrial Revolution.

|

|

Philippe de Loutherbourg, 17401812. French-born English painter and designer.

Born in Strasbourg, he settled in London in 1771, designing theatre sets for Garrick and Sheridan, publishing picuresque views of Britain, and painting large canvases mostly exalting the Sublime.

|

|

William Blake, 17571827. English printmaker, painter, and poet.

His work spans the late classical and early romantic periods, but his style in each of his many media is sui generis and infused with a strongly mystical bent.

|

|

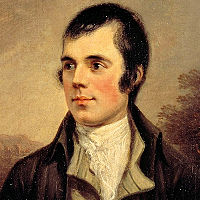

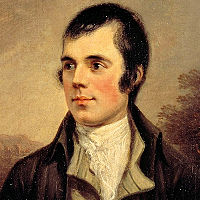

Robert Burns, 175996. Scottish poet.

Rabbie Burns is often regarded as the national poet of Scotland, where his birthday (1/25) is an occasion for the often-drunken singing of his many songs. His manner as "peasant-poet" was largely assumed; he was in fact quite well educated, and held his own with other figures of the Scottish Enlightenment. He wrote mainly in a Scottish dialect, but it is mostly intelligible to non-Scots.

|

|

Eli Whitney, 17651825. American inventor.

Whitney's invention of the cotton gin in 1793 was crucial to the economy of the Antebellum South. It also established him as an inventor, so that when (totally without experience) he contracted to produce rifles for the US Government in 1801, his offer was accepted. His solution to the problem was to build the guns out of interchangeable parts, the founding principle of all subsequent mass production.

|

|

William Wordsworth, 17701850. English poet, critic, and philosopher.

With the joint publication of the Lyrical Ballads with Coleridge in 1798, Wordsworth co-founded the English Romantic movement, and continued to dominate it for decades with poetry of his native Lake District and his doctrine of capturing experience direct from Nature for later use as "emotion recollected in tranquility."

|

|

John Heaviside Clark, 17711863. Scottish painter.

Clark was a Scottish aquatint engraver and painter of seascapes and landscapes. He was also known as Waterloo Clark, because of the sketches he made on the field directly after the Battle of Waterloo. [Wikipedia] The portrait is dubious.

|

|

Joseph Mallord William Turner, 17751851. English painter.

Rivaled only by Constable, Turner was the dominant British landscape painter of the first half of the 19th century, he started his career with topographical views intended for engraving, and ended with works whose subjects were dissolved in veils of paint and light.

|

|

Anthony Philip Heinrich, 17811861. American composer.

Heinrich was born in Bohemia, but came to America as a young man to stay with an uncle in Boston. When his uncle became bankrupt, he traveled by foot and canoe through the wilderness into Kentucky, where he settled into a log cabin and began to compose "some of the most original, if not strange, program music of the nineteenth century" [Wikipedia].

|

|

Samuel F. B. Morse, 17911872. American painter and inventor.

Morse had a successful career as a portrait painter, and became Professor of Art at New York University. Always curious about technical things, he introduced the Daguerreotype into America, and developed a single-wire telegraph system, greatly simplifying European models. He was co-inventor of the Morse Code, which is still used in telegraphy.

|

|

Alexis de Tocqueville, 180559. French writer.

Tocqueville was a French aristocrat a liberal politician. His two-volume Democracy in America (1835 and 1840) is valuable not only as an objective critique of the American system from an outsider, but a foundation work in sociology and political science.

|

|

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, 180661. English poet.

Elizabeth Barrett had established herself as a poet well before she met Robert Browning, whom she eventually married at the age of 40, and was disinherited by her father for doing so. Her sequence of love-letters to Browning, Sonnets from the Portuguese (1850) have been widely influential.

|

|

William Wyld, 180689. English painter.

Wyld started careers as a dipomat and a wine merchant, then turned to painting. With the support of the French painter, Horace Vernet, he spent time in Italy and France, painting mainly Orientalist subjects. But on visits back to Britain, he gained the patronage of Queen Victoria, and painted landscapes and watercolors in a rather simpler style.

|

|

Elizabeth Gaskell, 181065. English novelist.

The daughter of a Unitarian minister who gave up his position in the North for reasons of conscience, Mary Stevenson married another minister, who moved to Manchester, which became the disguised setting for North and South (1855). She published this, its predecessor Cranford (1853), and a biography of Charlotte Brontλ (1857) under the name "Mrs Gaskell," but used a pseudonym before that.

|

|

William Bell Scott, 181190. Scottish painter.

Born into an Ediburgh family of artists, Scott moved to London, where he became a member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. A post as head of the art school in Newcastle-on-Tyne from 1843 to 1864 brought him into contact with the industrial subjects which would form a significant part of his work.

|

|

Matthew Brady, 182496. American photographer.

Born in upstate New York, Brady studied under inventor Samuel Morse, who pioneered the daguerreotype technique in America. He opened his own studio in 1844, and went on to photograph U.S. presidents John Quincy Adams, Abraham Lincoln, and Martin Van Buren, among other public figures. When the Civil War began, Brady's use of a mobile studio and darkroom enabled thousands of vivid battlefield photographs to bring home the reality of war to the public. [Wikipedia]

|

|

George Inness, 182594. American painter.

Inness was a transitional figure in 19th-century American landscape. Beginning as a second-generation Hudson River School artist, he then went to France to study with the painters of the Barbizon School. His style back home developed from their example, through Tonalism, to something very close to Impressionism, but all in his own personal terms.

|

|

Alexander Smith, 182967. Scottish poet.

Born in Glasgow, Smith at first went into the family fabric business. The success of his first book of poems in 1853 led to his appointment as Secretary of Edinburgh University. There he met painter Horatio McCulloch who introduced him to the Isle of Skye and his future wife, leading him to spend increasing periods on the island.

|

|

Joseph Keppler, 183894. American cartooist.

Keppler was a scene designer and actor when he came to America from Austria in 1867. First in St. Louis and then in NYC, he began drawing cartoons which were immediately successful. He published them in his magazine Puck, employing other artists and his son Udo (18721956) when the workload became too heavy.

|

|

Jacob A. Riis, 18491914. Danish-American photographer.

Riis arrived in the US in his early 20s as a carpenter. Often destitute, and from time to time sleeping rough in alleys, he eventually found work as a journalist. These experiences led to his later fame as a social crusader, writing about the urban underbelly and photographing it (one of the first to use flash) for his 1890 book How the Other Half Lives,

|

|

William Rideing, 18531918. American writer.

The son of an officer on the Cunard Line, Rideing himself made many trips across the Atlantic, writing articles and books about Britain from an American point of view.

|

|

John Singer Sargent, 18561925. American painter.

Sargent was born in Florence, the son of wealthy cultured parents, and much of his career was spent in Europe, although his rising fame as the preeminent society portraitist of his day also took him back to America. He is said to have hated portraiture, though, and diversified into landscapes and watercolors for his own satisfaction.

|

|

Amy Beach, 18671944. American composer and pianist.

Her performing career as a child prodigy was curtailed by her marriage to a wealthy doctor, and for a long time she published her compositions under the name "Mrs. H.H.A. Beach." Most of her numerous works are small in scale, but her Gaelic Symphony of 1896 was the first symphony published by a woman in America.

|

|

Laura Ingalls Wilder, 18671957. American novelist.

The nine books in Little House on the Prairie series (193243) are all loosely based on Laura Ingalls' childhood moving with her pioneer settler family to Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Dakota Teritory.

|

|

Elizabeth Cotten, 18931987. American singer-songwriter.

Cotten (nιe Nevins) taught herself to play the guitar in an idiosyncratic left-handed style, writing her own songs and playing mainly in church. For most of her life she worked as a domestic servant, and did not begin professional performance until she was 60 and working for the well-known Seeger family of musicians, who encouraged her.

|