7. Empire.

There is a significant difference between the two countries in their use of the word Empire. By the time

of Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee in 1897, the British Empire was a source of national pride, spanning the

globe from Canada to New Zealand. Starting in the 1920s, Britain gradually ceded dominion over its colonies,

and critical opinion has shifted 180° to the point where colonialism is a dirty word. Still, any Briton

will acknowledge the Empire as an historical fact, however they see its legacy now.

In the early years of the United States, Empire was used quite freely, by Franklin, Washington, Jefferson,

and others, originally in a value-neutral context. But as the country gained power, the term American

Imperialism was heard more and more frequently, mostly in a negative sense, to refer to Manifest Destiny,

successive territorial acquisitions, occasional foreign intervention, and more recently to the global reach of

American companiesand always the term has been resisted by those who point out that hegemony and

empire are not at all the same thing.

So it is a difficult subject to talk about, made even more so by the fact that the related artifacts are often

more illustrations to history than objects of value in their own right. So I must apologize in advance for a

greater emphasis on political history in this class than I would ideally like, and a certain contentious tone

that may creep in despite my best endeavors! rb.

The script, videos, and images will be posted immediately after class.

TO THINK ABOUT

A lot of poems will be discussed in this class, and you may care to look at them in advance. They can be found at

the Texts link above.

Here are two paintings, not included in the class. Both show gatherings of "Indians," one in India itself around 1775,

the other in North America around 1850. What does each reveal of its culture, and the relationship of the artist to it?

Here are brief bios of the major artists considered in the class, listed in order of birth.

An alphabetical listing of artists for the whole course can be found at the

BIOS link on the syllabus page.

|

Francis Hayman, 170876. English painter.

Hayman began as a theatrical scene-painter, and later painted a large series of illustrations to Shakespeare. He was a founding member of the Royal Academy and its first librarian.

|

|

Benjamin West, 17381820. American painter working mainly in England.

Although he set up as a portraitist, it was as the painter of historical and mythological subjects that he made his name. A founding member of the Royal Academy in 1768, he became its president in 1792. His London studio became a Mecca for American artists studying abroad.

|

|

John Vanderlyn, 17751852. American painter.

After painting a portrait of Aaron Burr, the statesman virtually adopted him, sending him for five years to Paris to study, and giving him an apartment in his own home. Vanderlyn's career is chiefly noted for his portraits of other political figures, though he did some narrative paintings as well.

|

|

Edward Hicks, 17801849. American preacher and painter.

Although he began life as a sign-painter, his painting was mostly self-taught. His most frequent subject was The Peaceable Kingdom, a vision from Isaiah of a world in which all kinds of men and animals will live in peace with one another, an ideal in tune with his Quaker beliefs.

|

|

James Fenimore Cooper, 17891851. American novelist.

Cooper grew up in Cooperstown NY, a community founded by his father. After being expelled from Yale, he served first as a merchant seaman and then in the US Navy. The reputation of his large literary output, once much admired both at home and abroad, now rests mainly on his five Leatherstocking Tales, especially The Last of the Mohicans (1826).

|

|

Luigi Persico, 17911860. Italian sculptor.

Born in Naples, he moved to America in 1915, living in Baltimore and several cities in Pennsylvania before moving in 1824 to Washington, where he was involved in several projects for the sculpture of the US Capitol.

|

|

George Catlin, 17961872. American painter.

Catlin practiced law in Philadelphia before taking up painting; he was entirely self-taught. He is best known for his numerous depictions of Native Americans, and would spend large parts of each year staying in their camps as an honored guest.

|

|

Thomas Cole, 180148. American painter, born in England.

A founder of the Hudson River School. Towards the end of his career, he turned to grand historical and allegorical themes, of which The Course of Empire was one.

|

|

Horatio Greenough, 180552. American sculptor.

Greenough originally pursued an academic interest in the classics, studying at Harvard. During an extended stay in Rome with the painter Washington Allston, he became active as a sculptor in a classical style, leading to commissions at the US Capitol and elsewhere upon his return.

|

|

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 180782. American poet.

Longfellow was born in Maine, and taught at Bowdoin College and later at Harvard. His American themes and stirring diction made him the most popular poet of his day and earned him a reputation abroad. His Song of Hiawatha (1855) and similar poems employed the form of the Finnish Kalevala to create a similar Native American myth.

|

|

Alfred Lord Tennyson, 180992. English poet.

Known for his lyrical poems and his Arthurian epic Idylls of the King, Tennyson was appointed Poet Laureate to Queen Victoria in 1850 and held the position until his death. He adopted his characteristic tone of elegaic retrospection relatively early, and carried it through a long career that established him as the most resonant voice of the Victorian era.

|

|

William Tylee Ranney, 181357. American painter.

A noted if short-lived artist in pre-Civil-War America, Ranee painted scenes from everyday life, and was one of the first painters to depict the expanding West.

|

|

Thomas Jones Barker, 181382. English painter.

Born in Bath, the son of a minor painter, Barker moved to Paris in 1834 to study with Horace Vernet. After considerable success in France, he returned to England in 1845, becoming a fashionable portraitist and specialist in historical and battle pictures. His most famous picture, The Secret of England's Greatness (1863) is an icon of Empire, showing Queen Victoria handing a Bible to a kneeling Zulu chief.

|

|

Emanuel Leutze, 181668. German-American painter.

Leutze was born in Germany, came to America with his family at age 9, and began his career here. But he returned to Dόsseldorf from 1841 to 1859, and it was there that he painted his iconic Washington Crossing the Delaware, modeled in part by other American painters who had come over to study with him.

|

|

Edward Armitage, 181796. English painter.

Armitage

"was an English Victorian-era painter whose work focused on historical, classical and biblical subjects." [Wikipedia]

|

|

Charles Deas, 1818-67. American painter.

Deas became quite famous in his twenties for his highly dramatic paintings of Native Americans, fur trappers, and other frontier figures. He was committed to a mental asylum at age 30, and spent the remainder of his life there.

|

|

Albert Bierstadt, 18301902. American landscape painter.

Born in Germany, but living mainly in New York. Although a member of the Hudson River School, he became the painter par excellence of the American expansion to the Rockies and beyond.

|

|

Joseph Keppler, 183894. American cartooist.

Keppler was a scene designer and actor when he came to America from Austria in 1867. First in St. Louis and then in NYC, he began drawing cartoons which were immediately successful. He published them in his magazine Puck, employing other artists and his son Udo (18721956) when the workload became too heavy.

|

|

John Gast, 184296. American painter.

Gast emigrated with his family from Berlin as a child. He is best known for his painting American Progress (1872), an iconic expression of Westward Expansion. [There is no portrait available.]

|

|

Edward Elgar, 18571934. English composer.

Elgar was the leading figure in English music during the late Victorian and Edwardian eras. With works such as the Enigma Variations and his concerti for violin and cello, he was one of the first English composers after Purcell to achieve an international reputation.

|

|

Victor Gillam, 18581920. American cartoonist.

Yorskuire-born Gillam was an American political cartoonist, associated with Judge Magazine for 20 years. His best-known work covers the campaign and presidency of William McKinley.

|

|

Charles Marion Russell, 18641926. American painter.

Sometimes known as "the cowboy artist," Russell painted over 2,000 depictions of the American West including several bronze sculpture. He went beyond painting to become an ardent activist for Native American rights.

|

|

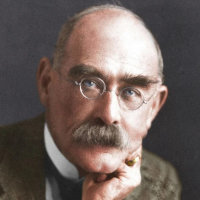

Rudyard Kipling, 18651936. English writer.

Kipling was born in India, the son of an educator. After boarding school in England, he returned to India and worked as a reporter, seven years that provided the background for most of his subsequent work. His story collection Plain Tales from the Hills (1888) did not sit well with the British colony, but made him a household name back in Britain, where he went from success to success, including being the youngest ever to win the Nobel Prize in Literature (1907). His masterpiece is probably the novel Kim (1901), but his output of poems and stories was prodigious. Hailed as the Poet Laureate of Empire in his time, his reputation declined with later reassessment of imperialism.

|

|

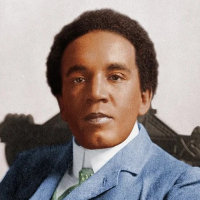

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, 18751912. English composer.

Son of a physician from Sierra Leone and an English mother, he studied at the Royal College of Music with Stanford. His compositions had some modest international success, but none to match the acclaim given to his three cantatas based on Longfellow's Hiawatha.

|

|

Irving Berlin, 18881989. American composer.

Berlin (b. Israel Beilin) arrived in the US from Russia at the age of 5. Although he could not read music and could barely play, he wrote over 1,500 songs with the aim, in his words, "to reach the heart of the average American." With hits like "Easter Parade," "White Christmas," "God Bless America," and the musical Annie Get Your Gun (1946), one might say he succeeded.

|