NOTE:

I have revised this class fairly extensively since first posting this page, making cuts throughout the first hour

to make room for additions at the end of it. The above handout does not reflect these changes.

8. Family Values.

Middle-class Victorians regarded morality and etiquette as badges of belonging. Proper British decorum was something

they carried with them into the colonies and assiduously practiced at home—at least in public. Victorian art is full

of paintings warning of the consequences of lapses from these standards, especially for women; men, as so often,

enjoyed a double standard.

For whatever reason, American art of the period offers few such examples, perhaps because the still-new nation faced

more existential dilemmas. Also while Victorian moral art was mainly situated within a bourgeois urban milieu, Americans

hankered after the simpler values of the country and distrusted distinctions of class. Their morality derived from Bibles

read at home, from the McGuffey Readers studied at school, and from an increasing sense of civic responsibility.

The second hour of the class will look at novels, in which authors worked through moral issues with equal intensity in both

nations. Each will be illustrated through text excerpts and videos.

The script, videos, and images will be posted immediately after class.

TO THINK ABOUT

Here are two street scenes, not included in the class, separated by a quarter-century and the Atlantic. Click for

larger versions, click the "QUESTIONS" link for suggestions on how to compare them, then click the similar link

for some answers.

Here are brief bios of the major artists considered in the class, listed in order of birth.

An alphabetical listing of artists for the whole course can be found at the

BIOS link on the syllabus page.

|

Thomas Hood, 1799–1845. English poet.

Called "the finest English poet between the generations of Shelley and Tennyson," Hood wrote both humorous and serious verse for various periodicals and a magazine that he himself published. For most of the last five years of his short life, he was confined to bed through ill health.

|

|

William Holmes McGuffey, 1800–73. American educator.

Growing up on the Ohio frontier, McGuffey began working as a teacher in his teens. Years later, when he was already a Professor of Ancient Languages at Miami University in Ohio, and an ordained Presbyterian minister, he was recommended by Harriet Beecher Stowe to write a series of school Readers for children. These are still used by homeschoolers today, largely on account of the strong moral lessons they teach along with basic literacy.

|

|

Nathaniel Hawthorne, 1804–64. American novelist.

His 1850 novel The Scarlet Letter is an American classic, addressing (among other things) the role of religion and personal freedom in American life. Many of his earlier stories have similar depths of symbolism and moral enquiry. He also wrote A Wonder-Book for Girls and Boys (1851), consisting entirely of retellings of Greek myths.

|

|

Richard Redgrave, 1804–88. English painter.

Although elected to the Royal Academy as a painter, he began his career as a designer of glassware and objets d'art, and worked for much of his life as an administrator in various museums and educational institutions.

|

|

Alexis de Tocqueville, 1805–59. French writer.

Tocqueville was a French aristocrat a liberal politician. His two-volume Democracy in America (1835 and 1840) is valuable not only as an objective critique of the American system from an outsider, but a foundation work in sociology and political science.

|

|

Franz Xavier Winterhalter, 1805–73. German painter.

Although of peasant stock, he became drawing master to the Margravine of Baden in 1828. Her father supported his further study, and he eventually became the most sought-after court painter in Europe in the mid-19th century.

|

|

Francis William Edmonds, 1806–63. American painter.

Edmonds had dual careers as a banker and a painter of American genre subjects influenced by Dutch art of the Golden Age.

|

|

Augustus Egg, 1816–63. English painter.

A close friend of Charles Dickens (who described him as "a dear, gentle litle fellow"), Egg favored literary and historical subjects. His most famous work, the morlizing triptych Past and Present (1858), is something of a departure, closer to the work of the Pre-Raphaelites. [The image is a detail of a portrait of the artist in 17th-century costume by Richard Dadd.]

|

|

George Frederic Watts, 1817–1904. English painter and sculptor.

Watts, who once said "I paint ideas, not things," was a British pioneer of the Symbolist movement, and many of his works have allegorical overtones. He was briefly associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, and influenced by DG Rossetti, and even more briefly married to the teenage Ellen Terry, 30 years his junior; Choosing, his 1864 painting of her, remained her favorite portrait.

|

|

George Eliot, 1819–1880. English novelist and poet.

"George Eliot" was the pen name of Mary Ann Evans, under which she published seven novels generally regarded as among the greatest in English literature; Virginia Woolf described Middlemarch (1872) as "one of the few English novels written for grown-up people." Her writing is notable for its realistic portrayal of English social life and its acute psychological insight.

|

|

Herman Melville, 1819–91. American writer.

Melville's Moby-Dick (1851) is a landmark in literature (not just in America) for its scope, its wealth of detail, and the apocalyptic scale of its vision. Although he wrote nothing else of this size, his earlier novels based on his time in the South Seas, his long short stories, and above all his posthumously published Billy Budd show a deep penetration into character and morality.

|

|

Eastman Johnson, 1824–1906. American painter.

Born in Maine, Johnson started his career as apprentice to a Boston Lithographer. He later moved to Europe to study with Emanuel Leutze and others. Returning to America, he specialized in portraits and genre scenes, often taken from African American life. He was a co-founder of the Metropolitan Museum.

|

|

Robert Lowry, 1826–99. American hymnwriter.

Lowry was an ordained Baptist minister who always insisted that preaching was his main profession. He is remebered today, however, as the writer of over 500 gospel hymns, including the perennial "Shall we gather at the river?"

|

|

William Holman Hunt, 1827–1910. English painter.

One of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, his paintings were noted for their vivid color, precise detail, religious or moral subjects, and profuse symbolism. His The Light of the World became one of the most reproduced paintings in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

|

|

Frank Blackwell Mayer, 1827–99. American painter.

Though born and trained in Baltimore, Mayer lived in Paris 1872–70. His work in Maryland includes two paintings in the Annapolis State House and a large group portrait of the Founders of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

|

|

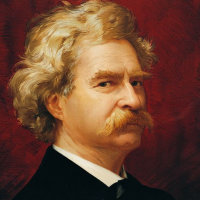

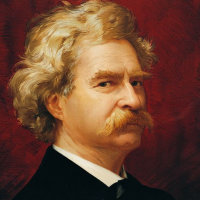

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (Mark Twain), 1835–1910. American writer.

Lacking success in his first careers as a river pilot and then as a mining engineer, he turned to journalism, then to novel writing (e.g. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, 1885), and is hailed variously as "greatest humorist this country has produced" (obituary) and "the father of American Literature" (Faulkner).

|

|

Ira D. Sankey, 1840–1908. American hymnwriter.

"Sankey was an American gospel singer and composer, known for his long association with preacher Dwight L. Moody in a series of religious revival campaigns in America and Britain during the closing decades of the 19th century. Sankey was a pioneer in the introduction of a musical style that influenced church services and evangelical campaigns for generations." [Wikipedia]

|

|

Thomas Hardy, 1840–1928. English novelist and poet.

Although thinking of himself primarily as a poet, Hardy is most often remembered as the author of pastoral realist novels set in "Wessex," his name for a large swath of Southwest England, the country that he loved. While Far From the Madding Crowd ends happily, more of his novels have an elegaic pessimism that is found also in his verse.

|

|

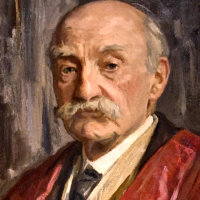

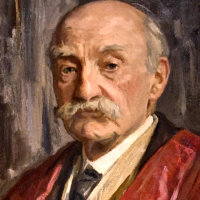

John Collier, 1850–1934. English painter.

Collier was a highly successful portraitist and painter of scenes from life, often with a "puzzle picture" element. He was connected through both his marriages to the family of Thomas Huxley, President of the Royal Society.

|

|

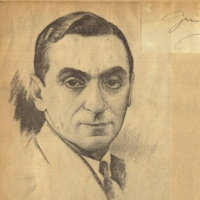

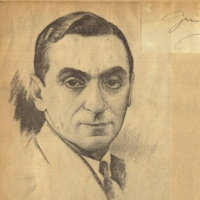

Irving Berlin, 1888–1989. American composer.

Berlin (b. Israel Beilin) arrived in the US from Russia at the age of 5. Although he could not read music and could barely play, he wrote over 1,500 songs with the aim, in his words, "to reach the heart of the average American." With hits like "Easter Parade," "White Christmas," "God Bless America," and the musical Annie Get Your Gun (1946), one might say he succeeded.

|

|

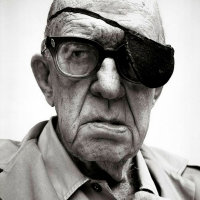

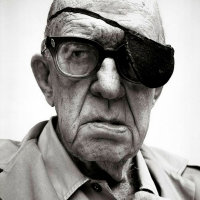

John Ford, 1894–1973. American filmmaker.

Ford (real name Feeney) was one of the most important directors in the middle decades of the century, making over 140 films and receiving 6 Oscars. He "made frequent use of location shooting and wide shots, in which his characters were framed against a vast, harsh, and rugged natural terrain" [Wikipedia].

|