9. The Sound of a Nation's Soul

Essentially, this class is a concert of 19th-century music: classical in the first hour, with more popular forms in the

second. Britain was a country with a long history of supporting music; for most of the 19th century, however, its composers

looked to German models rather than forming their own style. America, as a new country, had no such tradition, and its

19th-century history is largely one of developing a public that would appreciate and support the classics.

When dealing with the kinds of music that commanded a wider audience, it is possible to take the two countries together,

for both enjoyed musical theater, and both had a particular fondness for parlor songs and sentimental ballads. But the

same factors that originally isolated America as a classical country made it a rich breeding ground of folk traditions—whether

from the British Isles, Africa, or Latin America—and these would combine to make the country's unique contribution to world

music: jazz. rb.

The script, videos, and images will be posted immediately after class.

Here are brief bios of the major artists considered in the class, listed in order of birth.

An alphabetical listing of artists for the whole course can be found at the

BIOS link on the syllabus page.

|

William Billings, 1746–1800. American composer.

Originally a tanner by trade, he became one of the first American-born composers, essentially self-taught, writing hymns, somewhat more complex "fuguing tunes," and patriotic songs.

|

|

John Field, 1782–1837. Irish composer.

Born in Dublin, he made his début in London at age 9, and then came under the wing of Muzio Clementi, less as a pupil than an agent for his pianos, going with him all around Europe. He settled in St. Petersburg in 1803, where he spent the rest of his career. He is credited with inventing the piano Nocturne and thus influencing the music of Chopin and others.

|

|

Henry Bishop, 1787–1855. Engish composer.

'Sir Henry Rowley Bishop was an English composer from the early Romantic era. He is most famous for the songs "Home! Sweet Home!" and "Lo! Hear the Gentle Lark." He was the composer or arranger of some 120 dramatic works, including 80 operas, light operas, cantatas, and ballets. [He was also] Professor of Music at the universities of Edinburgh and Oxford.' [Wikipedia]

|

|

George Catlin, 1796–1872. American painter.

Catlin practiced law in Philadelphia before taking up painting; he was entirely self-taught. He is best known for his numerous depictions of Native Americans, and would spend large parts of each year staying in their camps as an honored guest.

|

|

Michael Balfe, 1808–70. Irish composer.

Balfe was born in Dublin and studied voice and violin. His singing career took him to Paris, Milan, and London, where he also began to get his own operas produced. The Bohemian Girl (1843), his greatest success (containing the air "I dreamt that I dwelt in marble halls") was produced in translation all over Europe, and even returned to London as an Italian opera!

|

|

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy, 1809–47. German composer.

A major figure in the Romantic movement and a precocious talent, he wrote many of his best-known works (such as the Midsummer Night's Dream overture) while still in his teens. By virtue of his ten separate residencies in England or Scotland, and the works he premiered there, he almost qualifies as a virtual British composer.

|

|

William Schwenk Gilbert, 1813–1911. English writer.

The author of many straight plays as well, Gilbert gained lasting fame as the librettist and theatrical genius behind the 14 operettas ("Savoy Operas") written with Arthur Sullivan between 1871 and 1896. These became almost as popular in America as the were in Britain.

|

|

William Henry Fry, 1813–64. American composer.

"Fry was the first known person born in the United States to write for a large symphony orchestra, and the first to compose a publicly performed opera.[1] He was also the first music critic for a major American newspaper, and he was the first known person to insist that his fellow countrymen support American-made music." [Wikipedia]

|

|

William Sterndale Bennett, 1816–75. English composer.

As a young pianist at the Royal Academy of Music, Bennett's compositions attracted the attention of Felix Mendelssohn, who took him to Germany and introduced him to Schumann; he spent three years in Leipzig before returning to London where his compositions (though Germanic in manner) attracted much attention. He remained an important figure in British musical life, his pupils including Hubert Parry and Arthur Sullivan.

|

|

George Frederick Bristow, 1825–1898. American composer.

Bristow's father was a professional musician, who taught him to play several instruments along with harmony, counterpoint, and orchestration. While still in his teens, he joined the NY Philharmonic as a violinist and remained with them for 35 years, rising to concertmaster. Meanwhile, he also conducted two choral societies and was active in establishing a music curiculum in public schools. His five symphonies all have extra-musical subjects.

|

|

Frederic Edwin Church, 1826–1900. American painter.

A pupil of Thomas Cole, Church was (with Bierstadt) the outstanding landscapist of the second generation of the Hudson River School. He was attracted to highly dramatic subjects, such as his Niagara, which made him famous, and traveled to the Andes and Middle East in search of them.

|

|

Stephen C. Foster, 1826–64. American composer.

Although associated with the antebellum South, Foster was born near Pittsburgh, and visited the South only once, on his honeymoon. But he made liberal use of Southern traditions and dialect in the numerous songs he wrote for minstrel shows, many of which have become folk songs in their own right. Contrasted with these are his sentimental ballads such as "Beautiful dreamer" and "I dream of Jeanie with the light brown hair," which show his remarkable gift for melody.

|

|

Louis Moreau Gottschalk, 1829–69. American composer.

Starting as a child prodigy in New Orleans, Gottschalk basically composed pieces to show off his own skills. Although rejected by the Paris Conservatoire, he made a name for himself there, impressing other virtuosi such as Liszt and Chopin. Even when he returned to the Americas, he spent most of his life in the Caribbean and Latin America, whose musics he embraced in his own.

|

|

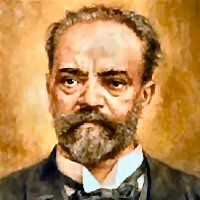

Antonin Dvorak, 1841–1904. Czech composer.

The best known of Czech composers, Dvorak composed nine symphonies and numerous chamber works. From 1885 to 1888, he was director of a new conservatory in Manhattan; he later became director of the conservatory in Prague. Of his ten operas, only the fairy-tale Rusalka (1901), a variant on the Little Mermaid story, has had true international success, cropping up in an astonishing range of productions in the last few decades.

|

|

Arthur Seymour Sullivan, 1842–1900. English composer.

Sullivan essentially had two careers: as a classical composer of orchestra music and oratorios on suitably uplifting subjects, and as the musical partner to W. S. Gilbert on the highly successful series of Savoy Operas from HMS Pinafore (1878) to The Gondoliers (1889) and beyond. History only remembers him in the latter role.

|

|

Thomas Eakins, 1844–1916. American painter.

Philadelphian Thomas Eakins is now counted among the greatest American-born painters of the 19th century, but in his day he was ridiculed for his insistence of realism in his portraits and scenes from everyday life. His legacy lives on, however, in the work of the Ashcan School and other painters at the turn of the century who began to give American art a distinct national style.

|

|

Charles Villiers Stanford, 1852–1924. Irish composer.

Born in Dublin, but educated in Cambridge, Stanford is most associated with academic positions, as Director of the Royal College of Music and Professor at Cambridge. A demanding teacher, his pupils included Coleridge-Taylor, Holst, and Vaughan Williams.

|

|

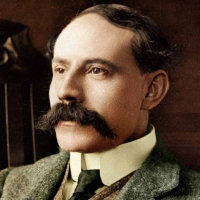

Edward Elgar, 1857–1934. English composer.

Elgar was the leading figure in English music during the late Victorian and Edwardian eras. With works such as the Enigma Variations and his concerti for violin and cello, he was one of the first English composers after Purcell to achieve an international reputation.

|

|

Victor Herbert, 1859–1924. American composer.

Born in the Channel Islands (though his mother told him Dublin), he went with her to Stuttgart, where he received training in cello and composition, leading to a career as an orchestral player and soloist, often in his own compositions. He came to the US in 1886 as principal cellist at the Met, and became conductor of the Pittsburgh Symphony in 194. His career trajectory changed completely in 1903, however, with the success of Babes in Toyland, the first of his many operettas.

|

|

Amy Beach, 1867–1944. American composer and pianist.

Her performing career as a child prodigy was curtailed by her marriage to a wealthy doctor, and for a long time she published her compositions under the name "Mrs. H.H.A. Beach." Most of her numerous works are small in scale, but her Gaelic Symphony of 1896 was the first symphony published by a woman in America.

|

|

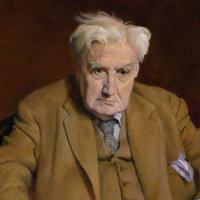

Ralph Vaughan Williams, 1872–1958. English composer.

Associated with the English folk song revival, he was more than anybody responsible for giving English music its national voice. He wrote nine symphonies and numerous vocal works, including the one-act opera Riders to the Sea. His first name is pronounced "Rafe."

|

|

Frederick Ashton, 1904–88. English choreographer.

Like most choreographers, Sir Frederick Ashton began as a dancer, and continued performing even as his fame blossomed as a choreographer. He became artistic director of the Royal Ballet in 1963, but had worked with the company and its various predecessors since 1935, responsible for creating many of the works that are the foundations of English ballet today.

|