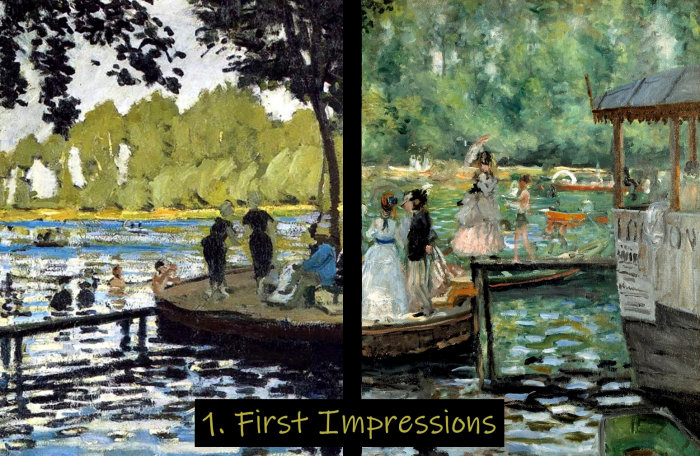

PAINTING: Originally announced as "The Human Factor," this class will concentrate on accessible pictures where the human situation is as significant as anything to do with art or style. As most of the paintings that first came to hand featured people eating or drinking, whether outdoors or in a restaurant, the class now has a new title: "Eating Out." The first comparison to be discussed is below.

Some questions: How does the lighting differ between the two pictures? Which has the greater depth? Are there any colors in one picture not found in the other, and if so why? What is the relationship between the scale of the figures and their surroundings? Are there any faces in either picture that could be used to identify the sitter? What is each painter most interested in?

POETRY: The second hour will continue the theme with five poems about picnics, from 1913 to 2020. Here is the beginning of one; please read the rest in advance.

There were never strawberries

like the ones we had

that sultry afternoon

sitting on the step

of the open french window

facing each other

your knees held in mine

the blue plates in our laps

the strawberries glistening

in the hot sunlight…

PEOPLE: Here are brief bios of the artists and poets we shall consider in the class, listed in

chronological order of birth. You can now access all biographies via the BIOS link on the

syllabus page.

|

Édouard Manet, 1832–83. French painter. Manet is arguably the greatest French painter in the third quarter of the 19th century. Though primarily a realist, he was influenced by older artists such as Titian and Velasquez. He was admired by the young Impressionists, became friends with Monet, and produced a number of works in their style, but he never exhibited with them, preferring to retain his own status in the official Salons. |

|

James Tissot, 1836–1902. French-born English painter. Tissot had a highly successful career as a society painter in Paris before he moved to London in 1871. His works, which now belong firmly in the history of British art, mostly depict affluent subjects in contemporary situations with a light narrative content. |

|

Claude Monet, 1840–1926. French Impressionist painter. The central figure in Impressionism (it was his Impression: Sunrise of 1872 that gave the movement its name), he intensified its focus more than any other artist, continuing well into the next century to produce series of paintings showing minute variations in the light and color in basically the same scene. Cézanne famously said of him, "Monet is nothing but an eye—but my God, what an eye!" |

|

Thomas Hardy, 1840–1928. English novelist and poet. Although thinking of himself primarily as a poet, Hardy is most often remembered as the author of pastoral realist novels set in "Wessex," his name for a large swath of Southwest England, the country that he loved. While Far From the Madding Crowd ends happily, more of his novel have an elegaic pessimism that is found also in his verse. |

|

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 1841–1919. French painter. A leading member of the Impressionist group, he began his career as a china painter in the Limoges factory, which—together with his admiration of Rococo masters such as Watteau and Fragonard—may have influenced the sweetness of color seen in much of his work. He was more concerned with detail, and more interested in figures than most of his colleagues. |

|

Henri Gervex, 1852–1929. French painter. Gervex began in an academic vein, but later devoted himself to depictions of modern Parisian life. Although many of his works show fishionable society, he could also paint workmen and the bourgeoisie. |

|

Edvard Munch, 1863–1944. Norwegian painter and printmaker. Tormented by the legacy of childhood trauma (he wrote "illness, madness, and death were the black angels that kept watch over my cradle"), Munch nevertheless managed to turn his neuroses into art that can stand with the most advanced painting in the rest of Europe and makes him a prime exponent of Expressionism. |

|

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, 1846–1901. French painter. A hunting accident in childhood (he came from an aristocratic family) left Toulouse-Lautrec permanently stunted in stature, but this condition gave him both an entrée into the seamier side of Paris and the realism to depict it as he found it, with plenty of glamor certainly, but without idealization or moralizing. |

|

John Sloan, 1871–1951. American painter. Sloan was one of a number of realist painters in New York in the early 20th century popularly known as "The Ashcan School" because of their fondness for less elevated subjects. Sloan himself was a committed Socialist. |

|

Rose Macaulay, 1881–1958. English novelist and poet. Coming from an academic family, Macaulay started writing early, and worked for the Government Propaganda Office during the First World War. The best-known of her novels, which were somewhat influenced by Virginia Woolf and share her committed feminism, is The Towers of Trebizond (1956), her masterpiece. |

|

Edward Hopper, 1882–1967. American painter. In all his career, Hopper maintained a balance between the social realism of his teacher Robert Henri, and the simplified forms of the abstraction that came into play soon after. Painting almost exclusively scenes from contemporary life, he managed to universalize the specific, and give everyday situations a powerful aura that transcended their literal subject. |

|

Norman Rockwell, 1894–1978. American painter and illustrator. Rockwell began working as a professional illustrator at 18, and continued to become one of America's best-loved artists. His success had partly to do with the circulation of the periodicals (notably The Saturday Evening Post that had him on their covers, and partly for his depiction of a family-friendly folksy America, but he was also an accomplished artist who could tackle serious subjects like racial and social injustice. |

|

Edwin Morgan, 1920–2010. Scottish poet. Born in Glasgow, educated there, and teaching at its university for most of his life, Morgan was the preeminent Scots poet of his generation, embracing Modernism but never constricted by it. He prized the graffito "CHANGE RULES!" as an ambiguity that nicely sums up his work. He became the first Makar, or Poet Laureate of Scotland, in 2004. |

|

Billy Collins, born 1941. American poet. One of the best-known and most approachable contemporary American poets, Collins was Poet Laureate of the United States between 2001 and 2003. |

The paintings discussed (or intended to be discussed) in the first hour of class are below. Click these links for the texts read in the second hour, and the script.

The Hardy poem, "Where the picnic was," has a beautiful setting by Gerald Finzi, for baritone and string quartet. There is also a film by Paula Downes, with some evocative images but less interesting music.

I mentioned that the Rose Macaulay poem might reference Dover Beach by Matthew Arnold; you can see that poem here. For the historical Charge of the Light Brigade, which was the background to the last poem we read, see here for the Wikipedia article on the battle, and here for the magnificent Tennyson poem. Both poems are short masterpieces, well worth your time.

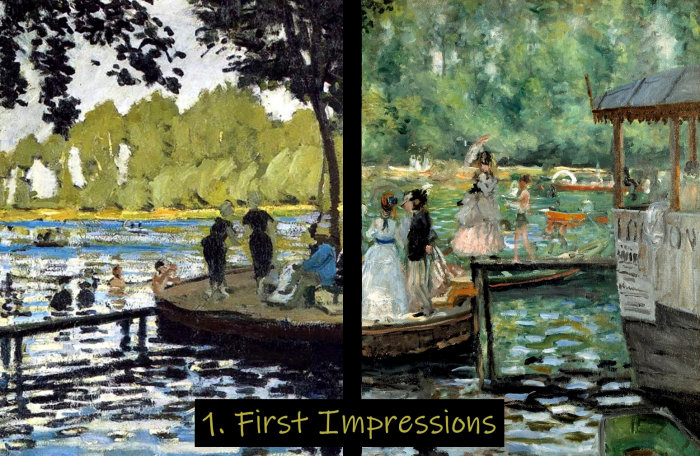

COMPARISON 1

Some questions: How does the lighting differ between the two pictures? Which has the greater depth? Are there any faces in either picture that could be used to identify the sitter? Are there any colors in one picture not found in the other, and if so why? What is the relationship between the scale of the figures and their surroundings? What is each painter most interested in?

Some facts: Manet exhibited his picture at the Salon des refusés in 1863; many people had come to laugh or condemn, and Manet gave them plenty to work with. Monet began his picture in direct response to Manet, but never finished it; the Musée d'Orsay has two sections, more or less completed; the smaller version at the Hermitage is a preliminary study. The bearded man in the dark suit is the painter Gustave Courbet.

Monet: Le déjeuner sur d'herbe, central panel (1866, Paris Orsay)

COMPARISON 2

Some questions: What is the month in each painting? Which would come over best in black-and-white? What meal is each group having, and how far has it progressed? Are there any narrative elements in either picture? Which seems the more natural, and which the more carefully designed?

Some facts: James Tissot (1836–1902) painted this picture in the garden of his own house in Saint John's Wood, London. Presumably this was bought from his earnings as a successful painter of Parisian society before he emigrated to London at the age of 35. The men are wearing the caps of the cricket club I Zingari.

Renoir: Luncheon of the Boating Party (1881, Phillips Collection)

Some questions: Does Renoir use the same style in painting the people, the landscape, and the objects? Is the lighting the same in all parts of the picture? How many separate conversations are there in the picture? Are there any figures who are not involved in talking with another? Does this give a sense of a real group of friends? Does your [now] knowing the identity of the people in the picture affect how you view it as a work of art?

Some facts: The Wikipedia article on this picture has detailed information on the identity of the sitters, and an interactive picture giving their names. The site is the Maison Fournaise at Chatou on the banks of the Seine; the two people leaning against the railing are the son and daughter of the proprietor.

Toulouse-Lautrec: At the Moulin Rouge (1892, Chicago)

Some questions: Does your knowing the identity of the people in the picture affect how you view it as a work of art? Do you think the sitters would have been identified in the exhibition catalogue? Between this and the Renoir, which stands better on its own regardless of the portrait element? How does each artist use the strong diagonal? Do any of the figures in either picture seem to caught in a spotlight, and what does that do?

Some facts: Five of the figures in this painting are performers: the red-haired Jane Avril seated with her back to us, the dancer La Goloue fixing her hair at the back, and three other dancers. The rest are the artist's friends. The diminutive Toulouse-Lautrec depicted himself in front of the tall man standing in the background.

COMPARISON 4

Some questions: [I showed these in class without titles or dates; the questions are based on that assumption.] What kind of a restaurant is depicted by each artist? In what country, and at what date? What is the social milieu? Do the people know each other? What, if any, are the narrative elements in each picture? Which painting do you think is larger in real life? Are there parts in either that especially remind you that this is not a photograph? What about the color range in each: is there are reason for each choice?

Some facts: Henri Gervex (1852–1929) began in an academic vein, but later devoted himself to depictions of modern Parisian life. Although many of his works show fishionable society, he could also paint workmen and the bourgeoisie. John Sloan (1871–1951) was one of a number of realist painters in New York in the early 20th century popularly known as "The Ashcan School" because of their fondness for less elevated subjects. Sloan himself was a committed Socialist.

COMPARISON 5

Some questions: Each of these pictures conveys a strong aura; haw would you describe it? What contributes to it: the space, the colors, the details, the faces of the women? Why did Hopper frame each scene in the way he did, and decide what to show and what not to show. If you did not know the dates (as you now do), which painting might you think was later? Neither of the women could probably be indentified from their faces alone; do you think that is deliberate, or a flaw?

Some facts: We tend to think of Edward Hopper (1882–1967) as the prime exponent of American anomie, but in fact many of his earlier paintings are vibrant and colorful. Automat is an unusually early example of his eye for urban loneliness.

Edward Hopper: Nighthawks (1942, Chicago)

Some questions: Do any of the people in the diner know one another? If so, what is their relationship? Is anybody talking? How do you get into the diner, and get out? What time of night is it? What would be the effect of cutting off the left-hand third of the canvas to reduce it to more normal proportions? Why did Hopper choose these particular colors?

Some facts: Watch this 8-minute video for more on the background to this painting than I can possibly summarize here. It is also a piece of quite brilliant artistic, biographical, and even historical analysis (the work was painted in the days immediately following Pearl Harbor).

Edvard Munch: Self-Portrait with Wine Bottle (1906, Munch Museum, Oslo)

Some questions: The painting is shown with thumbnails of Degas' Absinthe and Hopper's Automat; how does Munch's male figure compare with the women in these? Which is the most self-possessed, and which the weakest or most dejected? Is there any significance to the drinks shown in front of each sitter? Is the perspective in Munch's picture natural? What is the effect of the people in the background? In terms of paint, Munch's painting is the brightest and most freely handled of the three; does this make a difference? Does it matter if you know who the sitter is? [I showed it originally without title.]

Some facts: By his forties, Edvard Munch (1863–1944) had become an alcoholic, to such an extent that he collapsed in 1908 and had to check himself into an institution. This self-portrait from two years earlier may suggest something of that struggle, or reflect his lifelong tendency towards anxiety and depression.

COMPARISON 6

Some questions: The three versions above show Rockwell's complete picture preceded by two different ways of cropping it, as you commonly see; how does the narrative and meaning of the picture change in each case? If you were a writer, how might you fill out the stories of each figure or group in the picture? Do you think Rockwell intends you to do this? If so, how has he balanced or prioritized the various potential stories? And how far is it relevant to go with each one?

Some facts: Norman Rockwell (1894–1978) produced Saying Grace for the Thanksgiving 1951 edition of the Saturday Evening Post. Like all his works, it was based upon numerous sketches, followed by photographic sessions in his own studio, using friends and family as models (the boy is his son), and furniture borrowed from real diners.

PEOPLE: Here are brief bios of the artists considered in the class, in order of birth.

You can access all biographies via the BIOS link on the syllabus page.

|

Édouard Manet, 1832–83. French painter. Manet is arguably the greatest French painter in the third quarter of the 19th century. Though primarily a realist, he was influenced by older artists such as Titian and Velasquez. He was admired by the young Impressionists, became friends with Monet, and produced a number of works in their style, but he never exhibited with them, preferring to retain his own status in the official Salons. |

|

James Tissot, 1836–1902. French-born English painter. Tissot had a highly successful career as a society painter in Paris before he moved to London in 1871. His works, which now belong firmly in the history of British art, mostly depict affluent subjects in contemporary situations with a light narrative content. |

|

Claude Monet, 1840–1926. French Impressionist painter. The central figure in Impressionism (it was his Impression: Sunrise of 1872 that gave the movement its name), he intensified its focus more than any other artist, continuing well into the next century to produce series of paintings showing minute variations in the light and color in basically the same scene. Cézanne famously said of him, "Monet is nothing but an eye—but my God, what an eye!" |

|

Thomas Hardy, 1840–1928. English novelist and poet. Although thinking of himself primarily as a poet, Hardy is most often remembered as the author of pastoral realist novels set in "Wessex," his name for a large swath of Southwest England, the country that he loved. While Far From the Madding Crowd ends happily, more of his novel have an elegaic pessimism that is found also in his verse. |

|

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 1841–1919. French painter. A leading member of the Impressionist group, he began his career as a china painter in the Limoges factory, which—together with his admiration of Rococo masters such as Watteau and Fragonard—may have influenced the sweetness of color seen in much of his work. He was more concerned with detail, and more interested in figures than most of his colleagues. |

|

Henri Gervex, 1852–1929. French painter. Gervex began in an academic vein, but later devoted himself to depictions of modern Parisian life. Although many of his works show fishionable society, he could also paint workmen and the bourgeoisie. |

|

Edvard Munch, 1863–1944. Norwegian painter and printmaker. Tormented by the legacy of childhood trauma (he wrote "illness, madness, and death were the black angels that kept watch over my cradle"), Munch nevertheless managed to turn his neuroses into art that can stand with the most advanced painting in the rest of Europe and makes him a prime exponent of Expressionism. |

|

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, 1846–1901. French painter. A hunting accident in childhood (he came from an aristocratic family) left Toulouse-Lautrec permanently stunted in stature, but this condition gave him both an entrée into the seamier side of Paris and the realism to depict it as he found it, with plenty of glamor certainly, but without idealization or moralizing. |

|

John Sloan, 1871–1951. American painter. Sloan was one of a number of realist painters in New York in the early 20th century popularly known as "The Ashcan School" because of their fondness for less elevated subjects. Sloan himself was a committed Socialist. |

|

Rose Macaulay, 1881–1958. English novelist and poet. Coming from an academic family, Macaulay started writing early, and worked for the Government Propaganda Office during the First World War. The best-known of her novels, which were somewhat influenced by Virginia Woolf and share her committed feminism, is The Towers of Trebizond (1956), her masterpiece. |

|

Edward Hopper, 1882–1967. American painter. In all his career, Hopper maintained a balance between the social realism of his teacher Robert Henri, and the simplified forms of the abstraction that came into play soon after. Painting almost exclusively scenes from contemporary life, he managed to universalize the specific, and give everyday situations a powerful aura that transcended their literal subject. |

|

Norman Rockwell, 1894–1978. American painter and illustrator. Rockwell began working as a professional illustrator at 18, and continued to become one of America's best-loved artists. His success had partly to do with the circulation of the periodicals (notably The Saturday Evening Post that had him on their covers, and partly for his depiction of a family-friendly folksy America, but he was also an accomplished artist who could tackle serious subjects like racial and social injustice. |

|

Edwin Morgan, 1920–2010. Scottish poet. Born in Glasgow, educated there, and teaching at its university for most of his life, Morgan was the preeminent Scots poet of his generation, embracing Modernism but never constricted by it. He prized the graffito "CHANGE RULES!" as an ambiguity that nicely sums up his work. He became the first Makar, or Poet Laureate of Scotland, in 2004. |

|

Billy Collins, born 1941. American poet. One of the best-known and most approachable contemporary American poets, Collins was Poet Laureate of the United States between 2001 and 2003. |