PAINTING: With this class we get more into Art History than we have before. I am going

to show a number of Italian artworks from the 15th century—what Italians call the 1400s or quattrocento and

art historians dub the Early Renaissance—and compare them to works by the four greatest masters of the 16th

century (1500s, cinquecento, or High Renaissance): Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael, and Titian. My point

is to see if we can discern some fingerprints that may help us tell one period from the other. The three comparisons

below will all be addressed in class, together with several others.

POETRY: The second hour will consist of six sonnets about love, spread over four centuries.

Three are declarations of love, two are lamentations of love lost, and the last is a parody. If you can, please

read them in advance.

PEOPLE: Here are brief bios of the artists we shall consider in the class, listed in order of birth. You can access all biographies via the BIOS link on the syllabus page.

|

Donatello (Donato di Niccolo), 1386–1466. Florentine sculptor. The outstanding sculptor of his day, Donatello ranks with Brunelleschi in architecture and Masaccio in painting as a standard-bearer of the Renaissance. He studied under Ghiberti, but soon struck out on his own, producing an immense variety of work over a long career, showing technical daring, psychological insight, and a characteristic grace. |

|

Fra Filippo Lippi, 1406–69. Florentine painter. A reluctant friar, Lippi was released from his vows after an affair with a nun (that produced their painter son Filippino), but continued to sign himself "Brother Lippi." His exquisite drawing, pale color harmonies, and formal innovations set the standard for mid-quattrocento Florentine painting, as seen for example in the work of Botticelli and his son. |

|

Sandro Botticelli, 1445–1510. Italian painter. Botticelli's work was neglected for centuries, but he is now acknowledged as the leading Florentine painter of the later quattrocento. Although he produced numerous religious paintings, he is best known for two large mythological works: Primavera (c.1480) and The Birth of Venus (c.1485). |

|

Leonardo da Vinci, 1452–1519. Italian painter and polymath. With Michelangelo and Raphael, one of the triumvirate of artistic geniuses that crown the High Renaissance. He trained in Florence with the painter Andrea Verrocchio before moving to the court of Ludovico Sforza in Milan. He spent the last years of his life at the court of François I in France. The naturalism and luminosity of his painting, and his effects of sfumato (or modeling as if by smoke), were widely influential. It is his notebooks, however, that are the best testament to the range of his genius, containing remarkable observations of the natural world, and mechanical inventions centuries before their time. |

|

Filippino Lippi, 1457–1504. Florentine painter. The son and pupil of Filippo Lippi, he later studied with Botticelli, adopting a manner close to both masters. Although now overshadowed by these larger figures, he enjoyed a high reputation in his lifetime, being described by Lorenzo de' Medici as "superior to Apelles." |

|

Michelangelo Buonarroti, 1475–1564. Florentine sculptor, architect, painter, and poet. A towering universal genius, his work virtually defines the Italian High Renaissance. He made his name primarily as a sculptor in his native Florence, though he worked elsewhere as well. His most famous works, however, are in Rome: the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel (1508–12) and his work from 1546 as leading architect of the Basilica of St. Peters, one of a succession of masters who brought the building to its present form. |

|

Giorgione (Giorgio da Castelfranco), 1477–1510. Venetian painter. Almost nothing is known of his life, and the catalogue of his undisputed works is very small, his fame and influence are quite disproportionate to the size of his output. He was an exquisite colorist, the first to specialize in cabinet paintings for private patrons rather than religious commissions, and the first painter to subordinate subject matter to the evocation of mood. |

|

Raffaello Sanzio (Raphael), 1483–1520. Italian painter and architect. One of the towering geniuses of the Italian Renaissance, Raphael was born in central Italy, and worked there until 1508, when he moved to Rome to decorate several stanze in the Vatican for Pope Julius II, and later his successor Leo X. The influence of these and other works of the period can be seen in religious art for many centuries to come. He was also one of the many architects of St. Peters. |

|

Tiziano Vecellio (Titian), 1485–1576. Venetian painter. Arguably the greatest Venetian painter of the High Renaissance, he produced works in just about every genre over an exceptionally long career. Probably his greatest influence was in his handling of paint and use of color, which became a starting point for Rubens and others in the next century. |

|

Sir Philip Sidney, 1554–86. English poet and courtier. One of the most prominent figures of the Elizabethan age, and active as soldier, courtier, and diplomat, Sidney is also remembered for his long sequence of love sonnets (a precursor to Shakespeare's), and his romances Astrophel and Stella and The Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia. None of these, however, were published in his lifetime. |

|

William Shakespeare, 1564–1616. English poet and playwright. With almost 40 plays, 154 sonnets, and many longer poems, Shakespeare dominates English literature of his time, and world literature for ever after. To attempt a thumbnail biography would be both unnecessary and impossible. |

|

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, 1806–61. English poet. Elizabeth Barrett had established herself as a poet well before she met Robert Browning, whom she eventually married at the age of 40, and was disinherited by her father for doing so. Her sequence of love-letters to Browning, Sonnets from the Portuguese (1850) have been widely influential. |

|

George Meredith, 1828–1909. English poet and novelist. Meredith was a respected poet and relatively minor novelist of the Victorian era. His autobiographical sonnet squence Modern Love (1862), however, broke new ground in telling of the break-up of a marriage in psychologically realistic detail. |

|

Édouard Manet, 1832–83. French painter. Manet is arguably the greatest French painter in the third quarter of the 19th century. Though primarily a realist, he was influenced by older artists such as Titian and Velasquez. He was admired by the young Impressionists, became friends with Monet, and produced a number of works in their style, but he never exhibited with them, preferring to retain his own status in the official Salons. |

|

E. E. [Edward Estlin] Cummings, 1894–1962. American poet and painter In addition to several thousand poems, Cummings also wrote four plays and two novels; he painted his own portrait in the National Portrait Gallery. A leading modernist, he was known for radical experiments in orthography and punctuation, frequently including the elimination of upper-case letters, but he deprecated the use of this style for his own name. |

|

Gwendolyn Brooks, 1917–2000. American poet. Brooks was the first African American to win the Pulitzer Prize, and the first woman of her race to be appointed to the post now known as Poet Laureate of the United States. |

ART: The paintings discussed (or intended to be discussed) in the first hour of class are below.

For the poetry in the second hour, click here.

COMPARISON 1

Some questions: First, note the differences in scale: the Donatello is around 5ft tall, the Michelangelo is three times life size; how does that change the effect of each statue? What is the age of each figure? Where are we in the story? What are the similarities and differences in pose? What is the nature of the detail in each case? Would it be right to call either of them erotic, and what is the nature of that eroticism, if so?

Some facts: Donatello's sculpture was almost certainly produced for a private patron, most probably Cosimo de' Medici; it is the first free-standing male nude to have been produced sinced antiquity. Michelangelo's was originally intended for the roof of the cathedral, hence the scale, but it proved too enormous to be hauled up there.

Some concepts: The Michelangelo reflects an increasing focus on the heroic quality of the ideal human body. While quattrocento artists reveled in detail, the cinquecento generally subordinates this to the effect of the whole; this is an example of Heinrich Wölfflin's principle of multiplicity versus unity. Note too how Donatello's detail is closer to the art of drawing than to modeling.

COMPARISON 2

Some questions: What is going on in each picture, specifically the relationship between Mary and Jesus? What is the narrative effect of including Saint Anne (Mary's mother)? Both artists face the same problem of unifying a work with a dominant central figure with a number of smaller ones to the side of it; how has each artist handled it? What is the nature of the depth in each painting? What is in the background of each? Which painting would be easier to reproduce in a coloring book?

Sme facts: Very little is known about the Lippi picture, except that if the angel in front is his son Filippino (see below) this would place it in the mid-1460s. The Leonardo was probably commissioned by the French King Louis XII, but was never delivered; it is one of a number of paintings that Leonardo never let out of his studio, so in that sense at least it is unfinished.

Some concepts: Wölfflin makes two distinctions that apply to this comparison: the planar nature of many early Renaissance works versus the recessive compositions more common later, and the linear nature of one period versus the painterly quality of the other. However, while Leonardo does exemplify these two distinctions, he is sui generis in other respects: the characterisic "smokiness" (sfumato) that was his particular form of painterly softening, the strangely enigmatic background, and the very curious dynamic relationship of the three figures.

COMPARISON 3

Some questions: Describe the pose of each sitter. Compare the two artists' ways of handling depth. Which picture would reproduce better in a coloring book, and which parts in it would not reproduce? Compare the combination of colors in each picture.

Some facts: The subject of the Filippino portrait has not been identified. Raphael's sitter, Bindo Altoviti, was a wealthy young art patron and Raphael's friend; he later became one of the most influential bankers in 16th-century Europe.

Some concepts: Although Filippino uses the window frame and sky to indicate depth, it is in fact an instance of Wölfflin's planar category; it could easily be reproduced by a set of paper cutouts; Raphael's figure occupies a unified receding space. Compared to the linear outlines of Filippino, Raphael's depiction is clearly painterly.

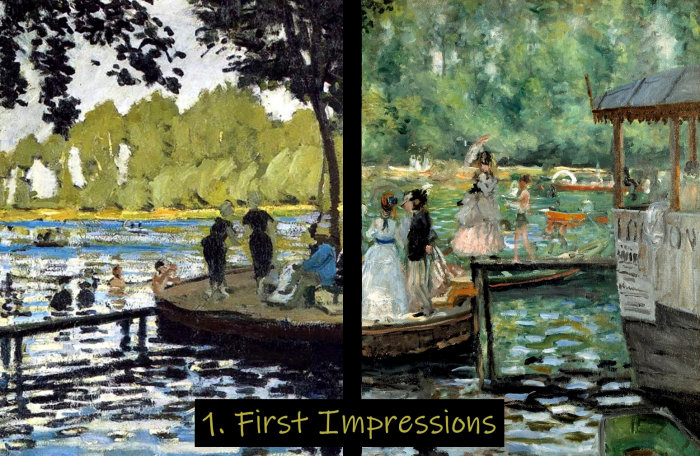

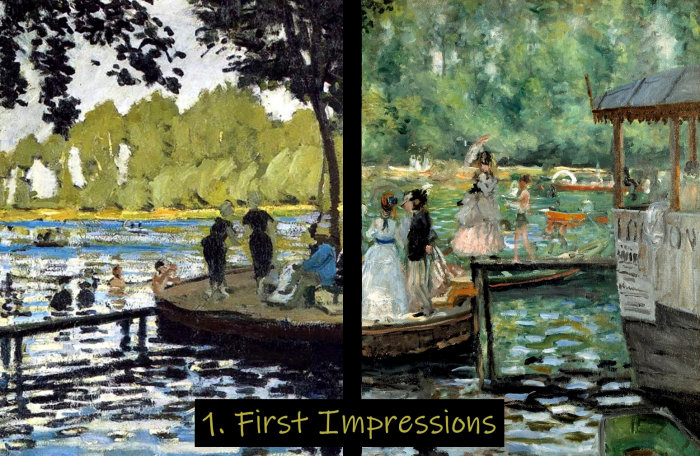

COMPARISON 4

Some questions: We can ask the same kinds of question as before: comparing the depth of the two paintings, the outlines of the figures, the color harmonies, the use of detail. Within that, we might also look at the roundness or modeling of the individual forms. In addition, how has each artist solved the problem of unifying a picture containing a central figure and several others? How would you describe the movement in each picture?

Some facts: Details of the commission for this and Botticelli's other large mythological painting, Primavera, are not known, but they both break new ground in depicting mythological scenes at such a scale. The subject here is the arrival of Venus on land, after being born out of the sea fully formed; she is wafted ashore by the winds and welcomed by Spring. Raphel depicts a similar aqueous triumph from a more obscure story; it was a commission to decorate a loggia for a banker.

Some concepts: Wölfflin's dichotomies are less clear here. Raphael's fresco is not as deep as many of his others, and the outlines of his figures are still quite sharp. In terms of the internal modeling of their musculature, however, even of the cherubs, he is entirely painterly. Also remarkable is Raphael's success in creating a balanced unityin a picture involving numerous figures, all of whom are in motion.

COMPARISON 5

Some questions: This is a good comparison, because the two nudes are nearly identical. Nearly, but not quite: what are the differences between them? Does it make a difference that one is asleep and the other awake? Is there any difference in the outline of the two figures? Look at the details of the right knee and lower legs of the two figures; what are the differences? What is the effect of including the dog? The biggest difference between the two is of course in the backgrounds; how does this affect (a) the composition, and (b) how you look at the picture? Which painting makes most use of curves? Which is more evocative of classical antiquity? Which figure is the more idealized?

Some facts: Current scholarship is beginning to attribute more to the hand of Titian in the picture than just the landscape, but this should make no difference to the comparison. Very little is known about the commission of either picture.

Some concepts: The main difference is how far each picture represents a neo-Platonic concept of ideal beauty; the pastoral setting and harmony of the earlier painting plays into this; the greater action and interior setting of the later one does not. Although the differences are slight, I find that the softer modeling of the later picture and the fact that you are able to see under the right leg to the space between them is indicative of subtle details that change the entire picture. Sir Kenneth Clark writes of the Dresden Venus: "she is like a bud, wrapped in its sheath, each petal folded so firmly as to give us the feeling of inflexible purpose. With Titian the bud has opened…."

Manet: Olympia (1863, Paris Orsay)

Some questions: What is the difference between the pose of Manet's nude and Titian's? She is not quite naked; do the little details matter? What does he indicate by turning the dog into a cat, the distant woman into a nearby black maid, the corsage into a presentation bouquet? How does each figure look out of the picture? What other differences can you see?

Some facts: This is the second of Manet's reinterpretations of Titian originals in a modern context; earlier the same year, he had turned the Louvre's Concert champêtre into the notorious Déjeuner sur l'herbe. The details in Olympia, indeed the very name, identify the woman as a prostitute, albeit operating on a fairly high level.

Titian: Bacchus and Ariadne (c.1523, London NG)

Some questions: Other than the main action, both the Raphael and the Titian contain many supporting figures; what are the different worlds they come from? Both pictures involve movement, but is it the same kind in each? How would you classify this picture in terms of Wölfflin's dichotomies of linear/painterly, planar/recessive, and multiplicity/unity (this last one is especially hard)?

Some facts: This is one of a series of mythological paintings commissioned by the Duke of Ferrara; another is Bellini's Feast of the Gods in the Washington NGA. Bacchus comes with his full retinue of bacchantes, in wild revelry. Even for Titian, the picture contains a lot of movement; he would be an inspiration for the baroque style a century later—which is the subject of the next class.

POETRY: The following links will take you to the recordings of the sonnets discussed in class

(all except for the Meredith, which I read myself); all have various visual images and/or titles, but none has the simple

printing of the text that I showed in class. I also include links to the texts of all six sonnets and to the script for this

part of the class.

Sir Philip Sidney (read by Stella Gonet)

E. E. Cummings (read by the author)

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (read by Helen Mirren)

Gwendolyn Brooks (read by Sylvia Freeman)

Shakespeare (read by Daniel Radcliffe)

• Texts of the six sonnets

• My conjectural target for Shakespeare's Sonnet 130

• Script for the second hour

PEOPLE: Here are brief bios of the artists considered in the class, in order of birth.

You can access all biographies via the BIOS link on the syllabus page.

|

Donatello (Donato di Niccolo), 1386–1466. Florentine sculptor. The outstanding sculptor of his day, Donatello ranks with Brunelleschi in architecture and Masaccio in painting as a standard-bearer of the Renaissance. He studied under Ghiberti, but soon struck out on his own, producing an immense variety of work over a long career, showing technical daring, psychological insight, and a characteristic grace. |

|

Fra Filippo Lippi, 1406–69. Florentine painter. A reluctant friar, Lippi was released from his vows after an affair with a nun (that produced their painter son Filippino), but continued to sign himself "Brother Lippi." His exquisite drawing, pale color harmonies, and formal innovations set the standard for mid-quattrocento Florentine painting, as seen for example in the work of Botticelli and his son. |

|

Sandro Botticelli, 1445–1510. Italian painter. Botticelli's work was neglected for centuries, but he is now acknowledged as the leading Florentine painter of the later quattrocento. Although he produced numerous religious paintings, he is best known for two large mythological works: Primavera (c.1480) and The Birth of Venus (c.1485). |

|

Leonardo da Vinci, 1452–1519. Italian painter and polymath. With Michelangelo and Raphael, one of the triumvirate of artistic geniuses that crown the High Renaissance. He trained in Florence with the painter Andrea Verrocchio before moving to the court of Ludovico Sforza in Milan. He spent the last years of his life at the court of François I in France. The naturalism and luminosity of his painting, and his effects of sfumato (or modeling as if by smoke), were widely influential. It is his notebooks, however, that are the best testament to the range of his genius, containing remarkable observations of the natural world, and mechanical inventions centuries before their time. |

|

Filippino Lippi, 1457–1504. Florentine painter. The son and pupil of Filippo Lippi, he later studied with Botticelli, adopting a manner close to both masters. Although now overshadowed by these larger figures, he enjoyed a high reputation in his lifetime, being described by Lorenzo de' Medici as "superior to Apelles." |

|

Michelangelo Buonarroti, 1475–1564. Florentine sculptor, architect, painter, and poet. A towering universal genius, his work virtually defines the Italian High Renaissance. He made his name primarily as a sculptor in his native Florence, though he worked elsewhere as well. His most famous works, however, are in Rome: the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel (1508–12) and his work from 1546 as leading architect of the Basilica of St. Peters, one of a succession of masters who brought the building to its present form. |

|

Giorgione (Giorgio da Castelfranco), 1477–1510. Venetian painter. Almost nothing is known of his life, and the catalogue of his undisputed works is very small, his fame and influence are quite disproportionate to the size of his output. He was an exquisite colorist, the first to specialize in cabinet paintings for private patrons rather than religious commissions, and the first painter to subordinate subject matter to the evocation of mood. |

|

Raffaello Sanzio (Raphael), 1483–1520. Italian painter and architect. One of the towering geniuses of the Italian Renaissance, Raphael was born in central Italy, and worked there until 1508, when he moved to Rome to decorate several stanze in the Vatican for Pope Julius II, and later his successor Leo X. The influence of these and other works of the period can be seen in religious art for many centuries to come. He was also one of the many architects of St. Peters. |

|

Tiziano Vecellio (Titian), 1485–1576. Venetian painter. Arguably the greatest Venetian painter of the High Renaissance, he produced works in just about every genre over an exceptionally long career. Probably his greatest influence was in his handling of paint and use of color, which became a starting point for Rubens and others in the next century. |

|

Sir Philip Sidney, 1554–86. English poet and courtier. One of the most prominent figures of the Elizabethan age, and active as soldier, courtier, and diplomat, Sidney is also remembered for his long sequence of love sonnets (a precursor to Shakespeare's), and his romances Astrophel and Stella and The Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia. None of these, however, were published in his lifetime. |

|

William Shakespeare, 1564–1616. English poet and playwright. With almost 40 plays, 154 sonnets, and many longer poems, Shakespeare dominates English literature of his time, and world literature for ever after. To attempt a thumbnail biography would be both unnecessary and impossible. |

|

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, 1806–61. English poet. Elizabeth Barrett had established herself as a poet well before she met Robert Browning, whom she eventually married at the age of 40, and was disinherited by her father for doing so. Her sequence of love-letters to Browning, Sonnets from the Portuguese (1850) have been widely influential. |

|

George Meredith, 1828–1909. English poet and novelist. Meredith was a respected poet and relatively minor novelist of the Victorian era. His autobiographical sonnet squence Modern Love (1862), however, broke new ground in telling of the break-up of a marriage in psychologically realistic detail. |

|

Édouard Manet, 1832–83. French painter. Manet is arguably the greatest French painter in the third quarter of the 19th century. Though primarily a realist, he was influenced by older artists such as Titian and Velasquez. He was admired by the young Impressionists, became friends with Monet, and produced a number of works in their style, but he never exhibited with them, preferring to retain his own status in the official Salons. |

|

E. E. [Edward Estlin] Cummings, 1894–1962. American poet and painter In addition to several thousand poems, Cummings also wrote four plays and two novels; he painted his own portrait in the National Portrait Gallery. A leading modernist, he was known for radical experiments in orthography and punctuation, frequently including the elimination of upper-case letters, but he deprecated the use of this style for his own name. |

|

Gwendolyn Brooks, 1917–2000. American poet. Brooks was the first African American to win the Pulitzer Prize, and the first woman of her race to be appointed to the post now known as Poet Laureate of the United States. |