PAINTING: The first hour will be devoted to comparisons between High Renaissance works (early 1500s) and those from the Baroque era in the 1600s. Depending on time, they may feature six different subjects, further explained in the notes below. Clicking on the images will give you examples of each type from an earlier period.

Sacra Conversazione. A type of altarpiece, showing the Madonna and Child, attended by Saints and other figures in silent conversation.

Assumption of the Virgin Mary. The Catholic doctrine that the Virgin Mary, following a deathlike sleep (the "dormition") was raised ("assumed") bodily into heaven.

David. Israelite shepherd lad who slays the Philistine Goliath with a stone from a slingshot, and is eventually anointed King.

Rape of Proserpina. The Greek or Roman myth in which Hades, King of the Underworld, captures the young girl Prosperpina to become his Queen. A compromise negotiated with Zeus reduced her time underground to the winter months only, thus giving us the cycle of the seasons.

Conversion of Saul. In the Acts of the Apostles, Saul journeys from Jerusalem to Damascus to persecute the Christians there. On the way, a bright light appears in the sky, throwing him from his horse and blinding him. He alone hears the voice in the sky saying "Saul, Saul, why persecutest thou me?" When he regains his sight, he changes his name and, as Paul, becomes the first great proselytizer for Christianity.

Royal portraits. Portraits of Kings and other rulers always have a political or dynastic function as well as being a representation of a human being.

BALLET: For the second hour, we shall change periods completely, to look at another

art of action, the pas-de-deux in ballet.

PEOPLE: Here are brief bios of the artists we shall consider in the class, listed in order of birth. You can access all biographies via the BIOS link on the syllabus page.

|

Giovanni Bellini, 14351516. Venetian painter. One of a family of artists, he more than anyone was responsible for developing the characteristic Venetian style of painting in layers of oils, no doubt learned from the Flemish masters. This gives his pictures their extraordinary light, whether portraits or religious subjects. |

|

Michelangelo Buonarroti, 14751564. Florentine sculptor, architect, painter, and poet. A towering universal genius, his work virtually defines the Italian High Renaissance. He made his name primarily as a sculptor in his native Florence, though he worked elsewhere as well. His most famous works, however, are in Rome: the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel (150812) and his work from 1546 as leading architect of the Basilica of St. Peters, one of a succession of masters who brought the building to its present form. |

|

Tiziano Vecellio (Titian), 14851576. Venetian painter. Arguably the greatest Venetian painter of the High Renaissance, he produced works in just about every genre over an exceptionally long career. Probably his greatest influence was in his handling of paint and use of color, which became a starting point for Rubens and others in the next century. |

|

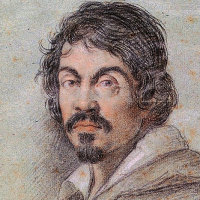

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, 15711610. Italian painter. Arguably the most original Italian painter at the start of the 17th century, he treated mostly religious subjects in a bold realist style that shocked his contemporaries, but was nonetheless widely influential. His figures tend to be large in proportion to the canvas, their actions and reactions dramatic, and their appearance that of ordinary working people. Caravaggio also often used concealed light sources that increases the drama of his depictions. |

|

Peter Paul Rubens, 15771640. Flemish painter and diplomat. One of the giants of baroque art, Rubens developed the style of Titian into a powerful rhetoric applied equally to sacred and profane subjects, and exerted enormous influence in Spain, England, and France as well as in his native Flanders, continued in the work of his many pupils. He position at so many courts also made him invaluable as a diplomat. |

|

Gianlorenzo Bernini, 15981680. Italian sculptor and architect. He is to the Italian Baroque what Michelangelo was to the Renaissance, the supreme master of many arts. The sense of movement and drama in his sculpture carries through into his architecture and even his town planning, such as the piazza before St. Peter's. |

|

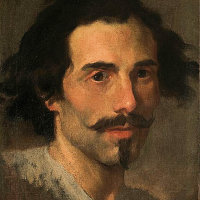

Anthony Van Dyck, 15991641. Flemish painter. For a time the principal assistant to Peter Paul Rubens, Van Dyck had a shorter but similarly stellar and varied career, painting in most of the major baroque genres. He was especially known as a portraitist, particularly in England, where he served the courts of both James I and Charles I. |

|

Marius Petipa, 18191910. French-Russian choreographer. After a career as a dancer in France and Spain, Petipa accepted a position with the Imperial Theatre in St. Petersburg, and remained in Russia the rest of his life. His work as the choreographer of The Sleeping Beauty, The Nutcracker, and the 1895 revival of Swan Lake made him one of the most influential choreographers of all time. |

|

George Balanchine, 190483. Georgian-American choreographer. After working with Diaghilev in Paris, Balanchine was invited to America in 1933 by Lincoln Kerstein, with whom he founded the New York City Ballet, remaining its artistic director for 35 years. One of the most influential choreographers of the century, he is especially noted for his abstract works with minimal decor but the greatest musicality. |

|

Jerome Robbins, 191898. American choreographer and director. Beginning his career as a dancer and later choreographer with the American Ballet Theatre, Robbins later joined forces with Balanchine in the New York City Ballet. While he created numerous ballets in the classical tradition, his career on Broadway and in film is at least as important, including his work on West Side Story in both media. |

|

Wayne McGregor, 1970 . English choreographer. McGregor is the first Resident Choreographer of the Royal Ballet to come from a contemporary dance rather than classical background. He has also worked in theater and film, and runs his own company in addition to his work with the Royal Ballet. |

ART: The art discussed (or intended to be discussed) in the first hour of class are below.

Click for the ballets in the second hour, and to look again at the

bios.

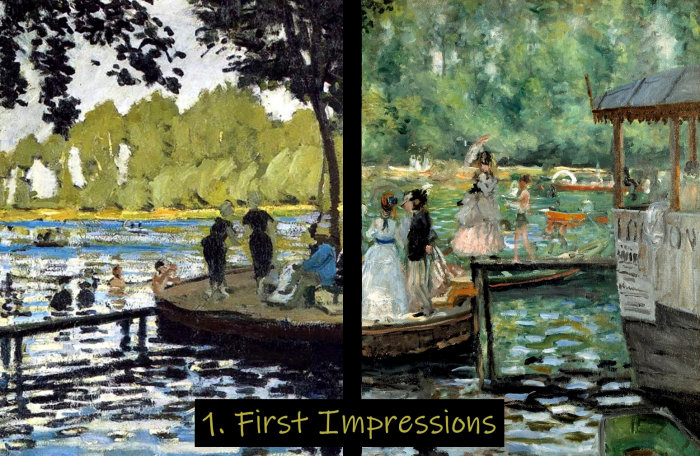

COMPARISON 1

Some questions: (1). Without worrying about who the figures actually are, what needs to be done to change the Bellini (left) into the Titian (right)? How many dimensions are in play in each picture? What is the effect of the two backgrounds? What is the compositional function of the flag? How would you decribe the balance in each picture?

(2). Is the vertical component an essential part of each subject? How does Titian handle it in each case? How many distinct vertical layers are there in each, and how does Titian link them? Which picture has the more sense of movement?

(3). Now ask the same questions of the Rubens: the vertical levels, the way they are linked, the sense of movement. Does Rubens have the same number of vertical elements? Does he look on the scene from the same angle, and how does this matter?

Further notes: The Bellini and two Titians are altarpieces in the great Venetian churches of San Zaccaria (Bellini) and the Frari (both Titians). The Rubens is a modello or detailed sketch for a large altarpiece in Antwerp Cathedral; Rubens' sketches often convey more of a picture's inner movement than comes through in the final work. The actual details of who is included in the two sacre conversazioni, and possibly the Assumptions also, would have been dictated by the patrons in each case. The Titan was painted for Jacopo Pesaro, who is seen kneeling with his family at bottom right.

COMPARISON 2

Sculptures of David by Michelangelo and Bernini

Some questions: The Bernini figure is life-size; the Michelangelo is almost three times larger; does this make a difference? What is the age of each figure? What stage in the story is being represented? Which figure is the more planar? Which has the more movement? What is implied by the difference in the faces? What is on the ground at David's feet?

Further notes: Bernini shows David actually in the act of fighting, a split second before he fires the stone that will hit Goliath. Everything about the sculpture contributes to its intense energy and implied movement, like a coiled spring about to be released. In the Bible, Saul gives him his own armor to protect him, but David prefers to fight without it, so the armor is shown on the ground.

COMPARISON 3

Some questions: Ask the same questions about Bernini's Proserpina as you did of his David: the twisting of the figures, the energy, the sense of movement. How many different directions of twist are there in the two figures? How does Bernini use a hard material (marble) to suggest soft ones (drapery and flesh)? The Rubens, of course, is literally motionless and flat, but how does he suggest movement, both in the individual figures and in the composition as a whole?

Further notes: It is probable that Rubens based his composition on a Roman sarcophagus similar to the one in the Walters. At any rate, he does not develop this particular subject in an implied third dimension, but he does give plenty of movement to individual figures and the strong left-to-right rush of the overall design. Bernini was only 23 when he executed this commission from Cardinal Scipione Borghese (who also commissioned the David). It is an entirely original solution, which was to influence sculpture for at least the next century.

COMPARISON 4

Some questions: Any painter of this subject is faced with a number of challenges: how to clarify the central action, how to divide the focus between Saul on the ground and whatever is happening in the heavens, and how to create a sense of the suddenness, scale, and power of this event. How do Michelangelo and Rubens address these problems? How does each use the elements of movement, lighting, and depth? Rubens uses a different style of costuming from Michelangelo's; what does he do with it? How does each artist treat the figure of Saul himself? What is the time of day?

Further notes: The Bible says that the other people in the group heard a sound but saw nothing; it is not clear whether they also saw the light. Both Michelangelo and Rubens, however, make it clear that the group has also experienced something cataclysmic; Rubens in fact uses the reactions of the soldiers and their horses as a major dramatic element. While Michelangelo's group is clearly traveling from front to back in the picture, it is not clear what plane is occupied by the heavenly figures. Rubens, however, makes these figures appear from the rear of the picture, so that the whole event is organized along an axis of depth.

COMPARISON 5

Some questions: What is the time of day in these two pictures, and is it the same in each? How many figures are represented? What costume choices has Caravaggio made, and are they the same in each version? And, comparing these back to the Michelangelo and the tradition of depicting the event as a crowd scene that would culminate in the Rubens, what is the effect of Caravaggio's extreme concentration of resources? Which of these two do you find the more ground-breaking, and/or the more effective? And what strong points can you find in the one you did not choose?

Further notes: The picture on the left, the more complex of the two, is the one that was rejected. However, it is not known quite why Caravaggio had to go back to his easel. The second version, though, stands as a perfect example of what Caravaggio did at his best: to reimagine old stories with striking lighting and the greates dramatic concentration, acted out by ordinary contemporary figures with all their dirt and wrinkles, and a complete absence of the heroic archetypes of Raphael and Michelangelo.

COMPARISON 6

Some questions: What image of kingship is Van Dyck portraying in each portrait? Which is the more human? If the previous comparisons have led you to form an concept of baroque style, are these fingerprints to be found equally in both pictures? Why might Van Dyck have included the King's riding master, M. de St. Antoine, in the equestrian portrait? Why did he include the draperies? The coat of arms is more complex than the one we usually see; why? What strikes you about the landscape in the other portrait? How does this compare with Van Dyck's later portrait of the King with his horse in the country?

Further notes: The idea of depicting a ruler or hero on a horse goes back to Roman sculpture. It was revived by Donatello in the early Renaissance, and then in painting by Titian. Van Dyck himself did several other equestian portraits beside these three of the King. The one with the triumphal arch is clearly intended to make political points; the 1637 one of Charles surveying the landscape from the back of a horse is also political, but more subtly so. The version in between, with the King dismounted, is the most subtle of the lot, and quite original in its idea of linking an off-duty king to the actual landscape of his kingdom.

Queen Elizabeth II on her 96th birthday (photo: Henry Dallal)

Further notes: This is the picture mentioned by Christina in connection with the second Van Dyck above. The Queen is shown with her fell ponies, named Bybeck Nightingale and Bybeck Katie. Official birthday photographs are a long-established custom.

BALLET: The two clips from Swan Lake and the "Hardest Button to Button" section from

Chroma are all available on YouTube in the Royal Ballet performances watched in class. Afternoon of a Faun

is available complete, but in a different performance, and the Balanchine/Ravel Sonatine can be found in a brief

clip only. Links are below.

Following on the comments made by Marilyn in class, I have added two other clips of Afternoon of a Faun. First,

the original 1955 casting of Jacques d'Amboise and Tanaquil LeClercq in black-and-white. Next, a comparison of the moments

leading up to the kiss from this version, the more modern one with Hervι Moreau and Juliette Gernez that is my first link

below, and the one with Vadim Muntagirov and Sarah Lamb of the Royal Ballet that I showed in class. You will see that Marilyn

is quite right: d'Amboise in the first is more masculine and the narcissistic element is played down; it is more present

in Moreau's performance, and absolutely the main theme in Muntagirov's. Just look at the timing of the very end of the

clip: Mutagirov turns away to the mirror before Lamb can look him in the eye after the kiss, but both the other two end

with a moment of visual contact, however brief. I assume that this is the work of whoever rehearsed the revival, but it

is consistent with the rest and, for my money, makes for a far more interesting though less romantic piece of theater.

Petipa: Swan Lake Act III pas-de-deux, entrιe and

adage

Petipa: Swan Lake Act III pas-de-deux, coda

Balanchine: Sonatine (excerpt only)

Robbins: Afternoon of a Faun (Moreau/Gernez)

Robbins: Afternoon of a Faun (d'Amboise/LeClercq)

Robbins: Afternoon of a Faun (comparisons)

McGregor: Chroma: The Hardest Button to Button

• Script for the second hour

PEOPLE: Here are brief bios of the artists considered in the class, in order of birth.

You can access all biographies via the BIOS link on the syllabus page.

|

Giovanni Bellini, 14351516. Venetian painter. One of a family of artists, he more than anyone was responsible for developing the characteristic Venetian style of painting in layers of oils, no doubt learned from the Flemish masters. This gives his pictures their extraordinary light, whether portraits or religious subjects. |

|

Michelangelo Buonarroti, 14751564. Florentine sculptor, architect, painter, and poet. A towering universal genius, his work virtually defines the Italian High Renaissance. He made his name primarily as a sculptor in his native Florence, though he worked elsewhere as well. His most famous works, however, are in Rome: the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel (150812) and his work from 1546 as leading architect of the Basilica of St. Peters, one of a succession of masters who brought the building to its present form. |

|

Tiziano Vecellio (Titian), 14851576. Venetian painter. Arguably the greatest Venetian painter of the High Renaissance, he produced works in just about every genre over an exceptionally long career. Probably his greatest influence was in his handling of paint and use of color, which became a starting point for Rubens and others in the next century. |

|

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, 15711610. Italian painter. Arguably the most original Italian painter at the start of the 17th century, he treated mostly religious subjects in a bold realist style that shocked his contemporaries, but was nonetheless widely influential. His figures tend to be large in proportion to the canvas, their actions and reactions dramatic, and their appearance that of ordinary working people. Caravaggio also often used concealed light sources that increases the drama of his depictions. |

|

Peter Paul Rubens, 15771640. Flemish painter and diplomat. One of the giants of baroque art, Rubens developed the style of Titian into a powerful rhetoric applied equally to sacred and profane subjects, and exerted enormous influence in Spain, England, and France as well as in his native Flanders, continued in the work of his many pupils. He position at so many courts also made him invaluable as a diplomat. |

|

Gianlorenzo Bernini, 15981680. Italian sculptor and architect. He is to the Italian Baroque what Michelangelo was to the Renaissance, the supreme master of many arts. The sense of movement and drama in his sculpture carries through into his architecture and even his town planning, such as the piazza before St. Peter's. |

|

Anthony Van Dyck, 15991641. Flemish painter. For a time the principal assistant to Peter Paul Rubens, Van Dyck had a shorter but similarly stellar and varied career, painting in most of the major baroque genres. He was especially known as a portraitist, particularly in England, where he served the courts of both James I and Charles I. |

|

Marius Petipa, 18191910. French-Russian choreographer. After a career as a dancer in France and Spain, Petipa accepted a position with the Imperial Theatre in St. Petersburg, and remained in Russia the rest of his life. His work as the choreographer of The Sleeping Beauty, The Nutcracker, and the 1895 revival of Swan Lake made him one of the most influential choreographers of all time. |

|

George Balanchine, 190483. Georgian-American choreographer. After working with Diaghilev in Paris, Balanchine was invited to America in 1933 by Lincoln Kerstein, with whom he founded the New York City Ballet, remaining its artistic director for 35 years. One of the most influential choreographers of the century, he is especially noted for his abstract works with minimal decor but the greatest musicality. |

|

Jerome Robbins, 191898. American choreographer and director. Beginning his career as a dancer and later choreographer with the American Ballet Theatre, Robbins later joined forces with Balanchine in the New York City Ballet. While he created numerous ballets in the classical tradition, his career on Broadway and in film is at least as important, including his work on West Side Story in both media. |

|

Wayne McGregor, 1970 . English choreographer. McGregor is the first Resident Choreographer of the Royal Ballet to come from a contemporary dance rather than classical background. He has also worked in theater and film, and runs his own company in addition to his work with the Royal Ballet. |