8. From Mount and Meadow.

The Arts in Britain at the start of the Nineteenth Century—poetry and painting at least—are linked by a sense that

physical surroundings such as weather and landscape are an intrinsic part of the national identity. We see this on

two scales. One is grand and heroic, inspired by the mountains of Scotland and the supposed poetry of Ossian; Turner

carries on this tradition to mid-century. The other, exemplified by Wordsworth, Constable, and the English

watercolorists, takes delight in the here and now, changing weather, and the familiar countryside.

A similar identification with nature can be found in the music and poetry of Germany at around the same time. But it

takes a different color, less particular, more symbolic, and with a sense that even secular subjects can have

transcendent overtones. We will study these aspects through the musical settings that Franz Schubert (all right, an

Austrain) made of verse by Goethe and others.

The script, videos, and images will be posted immediately after class.

Here are brief bios of the artists and poets considered in the class, listed in chronological order of birth.

You can access all biographies via the BIOS link on the syllabus page.

|

Edmund Burke, 1729–97. Irish writer and statesman.

Burke's 1757 treatise on The Sublime and the Beautiful was the first important discussion of the idea of the Sublime in art. His later career as a statesman, opponent of slavery, and supporter of freedom (though opponent of the French Revolution) is more important to history. The quotation "The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing" is probably not by him, though it fits his thinking.

|

|

James Macpherson, 1736–96. Scottish poet.

Macpherson leapt to fame with the publication of the epic Fingal in 1761, supposedly the work of the Gaelic poet Ossian, discovered and translated by him. Other works by Ossian followed. Although this was later exposed as a massive forgery, the mythical world of Ossian sparked something in the early Romantic fantasy, bringing worldwide fame to his supposed discoverer.

|

|

Philippe de Loutherbourg, 1740–1812. French-born English painter and designer.

Born in Strasbourg, he settled in London in 1771, designing theatre sets for Garrick and Sheridan, publishing picuresque views of Britain, and painting large canvases mostly exalting the Sublime.

|

|

Francis Towne, 1749–1816. English artist.

Towne never achieved fame in his day, but his watercolor landscapes, ranging from Rome to the English Lake District, show him to have been an exquisite artist and a significant forerunner of Romanticism.

|

|

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, 1749–1832. German poet, playwright, scientist, and statesman.

One of the great universal geniuses of the 18th century, Goethe epitomizes the transition between the Age of Reason and the Romantic era. His scientific works are still studied today, the two parts of his Faust hold a special place as an expression of moral philosophy, and his poems provided inspiration for Schubert and many other composers.

|

|

John Downman, 1750–1824. Welsh artist.

Although he pursued a successful career as a portrait painter, Downman does not seem to have depicted himself; the sitter of the portrait here is unknown. He also left a collection of exquisite sketches.

|

|

William Wordsworth, 1770–1850. English poet, critic, and philosopher.

With the joint publication of the Lyrical Ballads with Coleridge in 1798, Wordsworth co-founded the English Romantic movement, and continued to dominate it for decades with poetry of his native Lake District and his doctrine of capturing experience direct from Nature for later use as "emotion recollected in tranquility."

|

|

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, 1772–1834. English poet, critic, and philosopher.

With the joint publication of the Lyrical Ballads with Wordsworth in 1798, Coleridge co-founded the English Romantic movement. He went his own way in later years , however, exploring the more fantastic aspects of Romanticism with works like "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner" and "Kubla Khan." He became addicted to opium.

|

|

Caspar David Friedrich, 1774–1840. German painter.

The greatest German Romantic painter and a truly original visionary, he conceived images based on unconventional views of nature with strong, albeit enigmatic, moral implications.

|

|

Joseph Mallord William Turner, 1775–1851. English painter.

Rivaled only by Constable, Turner was the dominant British landscape painter of the first half of the 19th century, he started his career with topographical views intended for engraving, and ended with works whose subjects were dissolved in veils of paint and light.

|

|

John Constable, 1776–1837. English painter.

Even more than his contemporary Turner, Constable was the leading English landscape painter of the 19th century. Living in East Anglia, he was influenced by the Dutch landscapists painting very similar country. He made numerous outdoor sketches of clouds and trees, with free and brilliant handling of paint, but reverted to a more sober style in his paintings for exhibition.

|

|

John Sell Cotman, 1782–1842. English watercolorist.

Born in Norwich and essentially self-taught, he had six watercolors accepted by the Royal Academy at the age of 18. Known for his views of landscapes and buildings characterised by an extreme simplicity.

|

|

Franz Schubert, 1787–1828. Austrian composer.

Although he died before his 32nd birthday, Schubert was extremely prolific as a composer, writing symphonies, masses, chamber music, piano sonatas, and over 600 songs, both individually and in cycles. Though little known in his lifetime, his work was rediscovered and championed by Mendelssohn, Liszt, and Brahms, making him in effect the source of the German Romantic movement.

|

|

Friedrich Silcher, 1789–1860. German composer.

Under the influence of Weber, Silcher abandoned his studies of theology to devote himself to music. An important collector and arranger of German folk song, he also contributed many of his own, most notably Die Loreley, which has become a popular standard.

|

|

John Linnell, 1792–1882. English artist.

A pupil of Benjamin West, Linnell made a career as a portraitist and landscape painter, and later as an engraver. He continued the romantic style of landscape painting into the middle of the century.

|

|

Wilhelm Müller, 1794–1827. German lyric poet.

He is best known for his two lyric cycles, Die Schöne Müllerin and Winterreise set to music by Franz Schubert.

|

|

Henrich Heine, 1797–1856. German poet.

Raised as a Jew, Heine converted to Lutheranism in adolescence. His early lyric poetry was especially attractive to composers; Schumann's setting of his Dichterliebe ("Poet's Love"), for example, established itself as a masterpiece for both artists. The outspoken liberalism of his later verse caused it to be banned in many German jurisdictions, and he spent the last 25 years of his life as an exile in France.

|

|

Moritz von Schwind, 1804–71. Austrian artist.

A friend of Schubert as a young man, Schwind illustrated several of his songs. He went on to become one of the chief narrative painters of his time, principally painting subjects derived from German literature and myth.

|

|

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 1807–82. American poet.

Longfellow was born in Maine, and taught at Bowdoin College and later at Harvard. His American themes and stirring diction made him the most popular poet of his day and earned him a reputation abroad. His Song of Hiawatha (1855) and similar poems employed the form of the Finnish Kalevala to create a similar Native American myth.

|

|

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy, 1809–47. German composer.

A major figure in the Romantic movement and a precocious talent, he wrote many of his best-known works (such as the Midsummer Night's Dream overture) while still in his teens.

|

|

Robert Browning, 1812–89. English poet.

Although best known today for his lyrical and shorter narrative verse, Browning established a reputation as a leading Victorian poet also through longer works such as the play Pippa Passes (1841) and the novel-length The Ring and the Book (1869).

|

|

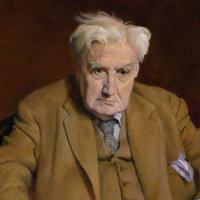

Ralph Vaughan Williams, 1872–1958. English composer.

Associated with the English folk song revival, he was more than anybody responsible for giving English music its national voice. He wrote nine symphonies and numerous vocal works, including the one-act opera Riders to the Sea. His first name is pronounced "Rafe."

|

|

Gustav Holst, 1874–1934. English composer.

The son of a church organist of Swedish descent, Holst studied first the piano and then the trombone. With Ralph Vaughan Williams, he was largely responsible for the revival of interest in English folk music at the turn of the century. He worked most of his life as a church musician and in education, but wrote numerous works, of which The Planets (1918) is the largest and most famous.

|

|

Sir Arnold Bax, 1883–1953. English composer.

His seven symphonies and numerous symphonic poems show his late-Romantic style. This later went out of fashion, though he was appointed Master of the King's Music in 1942. Bax also wrote fiction and verse under a pseudonym.

|

|

Rupert Brooke, 1887–1915. English poet.

Brooke is today best known for his 1914 sonnet The Soldier ("If I should die, think only this of me"), which maintained a nobility that other war poets decried. Strikingly handsome (Yeats called him "the handsomest young man in Engand"), he had achieved great popularity before he died of sepsis from a mosquito bite on the way to Gallipoli.

|