9. Life on the Fringe.

Artists seeking to express the national identity of their land have four strategies at their disposal. They can turn

to the country’s history as writer Adam Mickiewicz and painter Jan Matejko did in a Poland virtually

obliterated by partition. They can turn to legend, as folklorist Elias Lönnrot did in compiling old legends to

create a Finnish national epic, the Kalevala. They can revive a language, as Alexander Pushkin did with

Russian, freeing it from domination by the French of the courts and corruption by the vernacular of the fields. And in

all these countries, they can turn to the land itself, its physical beauty, the characteristics of its people, and its

traditions of music and dance.

Unlike other classes in the course, this one will focus less on style than on purpose: the forces, political or otherwise,

that shape great art out of subservience or disaster, often as a matter of national survival. rb.

The script, videos, and images will be posted immediately after class.

Here are brief bios of the artists and poets considered in the class, listed in chronological order of birth.

You can access all biographies via the BIOS link on the syllabus page.

|

Orest Kiprensky, 1782–1836. Russian painter.

The leading Russian portraitist of the early Romantic era, Kiprensky is best known for his portrait of Pushkin. He divided his life between Moscow and Rome.

|

|

Adam Mickiewicz, 1798–1855. Polish poet.

Mickiewicz was born in Polish Lithuania under Russian occupation. His support of Polish independence as a young man led to a five-year exile in Russia itself, after which he moved to Paris. It was there that he wrote his book-length poem Pan Tadeusz (1834), now regarded as the Polish national epic. He continued to support Polish causes from outside the country until he died in Istanbul, raising Polish forces to fight the Russians in the Crimean War.

|

|

Alexander Pushkin, 1799–1837. Russian poet.

While in exile because of verses critical of the Tsar he wrote his most celebrated play Boris Godunov. His masterpiece is the novel in verse Eugene Onegin, serialized between 1825 and 1832. While his range is extraordinary and an inspiration to later Russian composers, he is celebrated as much for restoring the Russian language (as opposed to French) as the vehicle for artistic expression.

|

|

Elias Lönnrot, 1802–84. Finnish folklorist.

Lönnrot was "a Finnish physician, philologist. and collector of traditional Finnish oral poetry. He is best known for creating the Finnish national epic, Kalevala, (1835, enlarged 1849), from short ballads and lyric poems gathered from the Finnish oral tradition" [Wikipedia].

|

|

Fryderyk Chopin, 1810–49. Polish composer.

Chopin was a virtuoso pianist (though for the most part avoiding the concert stage), and wrote almost exclusively for the piano, in a variety of shorter forms, many reflecting the dances of his native Poland, which he left at age 20 to escape the consequences of a revolution. He spent his adult life in Paris, where he was a frequent guest at salons. He maintained a long relationship with the writer George Sand.

|

|

Franz Liszt, 1811–86. Hungarian composer.

Liszt was the foremost piano virtuoso of his time, playing three or four concerts a week during his heyday during the 1840s, and much of his prolific output—including notably his set of 19 Hungarian Rhapsodies—is designed for display. But he was also a generous supporter of numerous other musicians, including Chopin, Schumann, Berlioz, Grieg, Borodin, and Wagner (who became his son-in-law). Many of his compositional techniques in his later works paved the way for advanced composers at the turn of the century,

|

|

Mikhail Lermontov, 1814–41. Russian poet.

Lermontov is hailed as the greatest Russian poet after Pushkin, but he was also a prose writer—his novel A Hero of Our Time (1840) has a hero much like Pushkin's Onegin—an army officer, and accomplished painter. He was particularly attracted to the Caucasus region of Russia.

|

|

Alexander Borodin, 1833–87. Russian composer.

A medical doctor and research chemist, he only composed music as an amateur (as did many of his contemporaries in the "mighty handful"). But works like his tone poem In the Steppes of Central Asia (1889), his unfinished opera Prince Igor, and some of his chamber music sing in a distinctive and often haunting Russian voice.

|

|

Jan Matejko, 1838–93. Polish painter.

Working mainly in Krakow, Matejo painted mainly subjects from Polish history. Although there is little new about his rich painterly style, which looks back to baroque traditions, he was utterly contemporary in his choice of themes from the past to address current issues in a partitioned Poland that had ceased to exist as an independent nation. The image is a presumed self-portrait from his painting Stanczyk.

|

|

Modest Mussorgsky, 1839–81. Russian composer.

Like many of his fellow nationalist composers among the "Famous Five," Mussorgsky had another profession, in his case as an army officer. His musical style as shown in his operas such as Boris Godunov (1869–74) and Khovanshchina (1873, unfinished) apeeared to his contemporaries as crude, and for many years his works were performed in edited editions, but recent productions have revealed the vigor of his highly original style.

|

|

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, 1840–93. Russian composer.

Tchaikovsky was the first Russian composer to gain an international reputation, in part because his Russian voice was allied to a thorough training in Western parctice. His symphonies, tone-poems, and ballets have become staples of their repertoire, but his dozen operas are less well-known, except for Eugene Onegin (1879) and The Queen of Spades (1890), both based on texts by Pushkin.

|

|

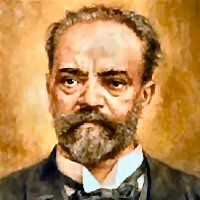

Antonin Dvorak, 1841–1904. Czech composer.

Dvorak composed ten operas, many of which have a continued presence in his native land. But only his fairy-tale opera Rusalka (1901), a variant on the Little Mermaid story, has had true international success, cropping up in an astonishing range of productions in the last few decades.

|

|

Edvard Grieg, 1843–1907. Norwegian composer.

A member of a musical middle-class family in Bergen, Grieg studied at the Leipzig Conservatory, then moved to Copenhagen, where he began his career as a pianist. It was only then that national characteristics of folk-song, rhythm, and harmony began to enter his work. He became in effect the leading composer of Norwegian nationalism, much as Sibelius was in Finland, but less aggressively so, expressing himself mainly in shorter forms, belonging to the salon rather than the symphony hall.

|

|

Nicolay Rimsky-Korsakov, 1844–1908. Russian composer.

Though a naval officer in professional life, Rimsky was the most brilliant orchestrator of the "Famous Five," and responsible for completing Borodin's Prince Igor and preserving Mussorgky's Boris Godunov for many decades in more conventional clothing. His own operas such as The Invisible City of Kitezh (1904) and The Golden Cockerel (1907), are staples of the Russian repertoire, but less frequently produced elsewhere.

|

|

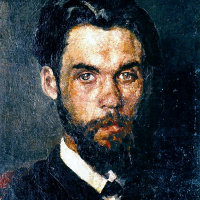

Ilya Repin, 1844–1930. Russian painter.

The leading Russian painter of his day, and the first to achieve international renown with specifically Russian themes, Repin painted numerous portraits and scenes from Russian myth and history. Although he left Russia before the Revolution, never to return, he was still extolled as a model for Socialist Realism, a label that dishonors the verve and spontaneity of his painting at its best.

|

|

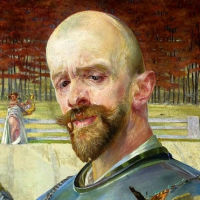

Jacek Malczewski, 1854–1929. Polish painter.

Malczewski was the leading painter of the late-19th-century Young Poland movement of artists seeking to reassert the Polish identity after a century of partition. "His creative output combined the predominant style of his times with historical motifs of Polish martyrdom, the romantic ideals of independence, Christian and Greek mythology, folk tales, as well as his love of the natural world" [Wikipedia]. His later works are much influenced by Symbolism.

|

|

Mykola Pymonenko, 1862–1912. Ukrainian painter.

A realist painter, he specialized in celebrations of ordinary Ukrainian life and customs. He became the teacher of Kasimir Malevich.

|

|

Akseli Gallen-Kallela, 1865–1931. Finnish painter.

Although considered the leading painter of Finnish nationalism, largely for his use of themes from the Kalevala, Gallen-Kallela grew up in a Swedish-speaking family, and lived for extended periods in Paris, Berlin, Nairobi, and Taos NM.

|

|

Jean Sibelius, 1865–1957. Finnish composer.

Sibelius "is widely regarded as his country's greatest composer, and his music is often credited with having helped Finland develop a national identity during its struggle for independence from Russia" [Wikipedia]. In addition to his seven symphonies, at least two of which have become repertoire standards, he wrote a number of tone poems based on Finnish history and myth, such as Finlandia, Tapiola, the >Lemminkainen Legends, and the Karelia Suite.

|