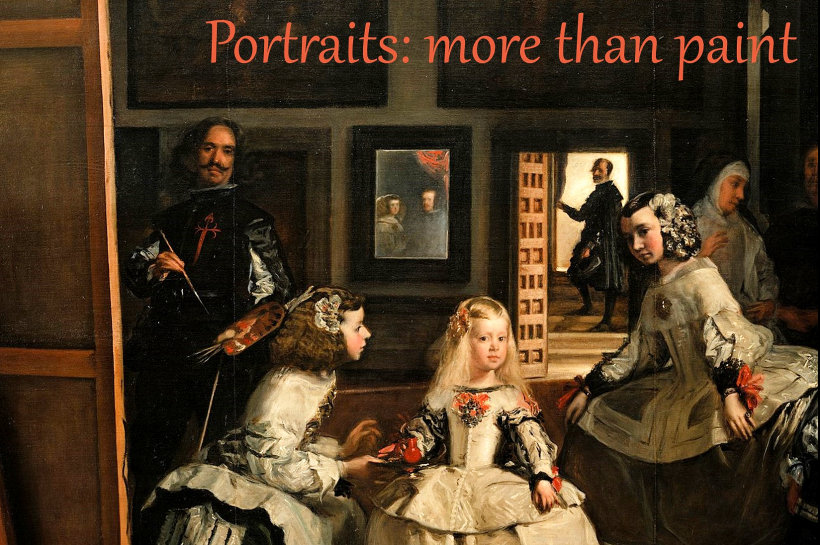

1. Catching a Likeness.

What makes a portrait different from any other work of art involving people? One possible answer is that it has

to capture the likeness of the person represented—but then a photograph can do that too. Let's talk about

photographs, then: what makes a portrait different from a casual snap? Three things, I would suggest: it needs

some kind of formal quality, it needs to transcend the moment, and it needs to make a statement. The same criteria

apply to paintings, sculpture, or any other kind of portrait.

Making a statement implies that a portrait in any medium must have a purpose. In the first two thirds of today’s

class, we shall look at many kinds of portraits and their function. Some of the categories, in alphabetical order,

are: portrait-as-allegory, portrait-as-art, portrait-as-bio, portrait-as-character, portrait-as-diagnosis,

portrait-as-document, portrait-as-memorial, portrait-as-proxy, portrait-as-publicity, portrait-as-query,

portrait-as-sentiment, portrait-as-social-validation, and self-portrait-as-signature.

In the last third of the class, we shall sample two media that might otherwise be under-represented later: the

biographical video clip, and some rare cases of portraits in music. rb.

The script, videos, and images will be posted immediately after class.

WHAT IS A PORTRAIT?

In this first class, we will consider some of the many answers to this question. As a way of thinking about it

in advance, however, consider these nine Degas pictures, not included in the class. All involve figures. A few

are frankly portraits; a few others are clearly not; and a few more occupy an ambiguous area in the middle.

Look through them first without titles and try to decide which is which.

1/9. CLICK IMAGE FOR NEXT

2/9

3/9

4/9

5/9

6/9

7/9

8/9

9/9

1/9. Place de la Concorde

2/9. The Bellelli Family

3/9. The Orchestra of the Opera

4/9. At the Café-Concert; the Song of the Dog

5/9. Mary Cassatt Seated, Holding Cards

6/9. L'Absithe

7/9. The Millinery Shop

8/9. Woman Seated Beside a Vase of Flowers

9/9. Portrait of Mlle. Hortense Valpinçon

When you’re ready, click the link below to see each again with its title. If the

exhibited title mentions the person’s name, does that automatically make the picture a portrait? What if we

know who the person is, but they are not part of the title? What if there is more than one person in the

picture? Can a depiction of someone in a casual setting also be a portrait? Must a portrait be in response to

a formal commission (none of these examples are)? I'll offer some tentative answers to these questions

here, but we will discuss such things in class.

[SHOW TITLES]

[SOME ANSWERS]

|

SOME PARTIAL ANSWERS: There are different categories, depending on the artist's

relationship to the sitter or model:

|

| • |

Portraits commissioned by a third party for a fee would be unarguable, but nothing here is in that category.

|

| • |

The pictures of the Bellellis (2), Cassatt (5), and Mlle Valpinçon (9) at least declare themselves as portraits,

though they are of friends and not done for money.

|

| • |

Place de la Concorde (1) and Woman with the Flowers (8) were also modeled by friends; the people

are attractively presented in a meaningful context, but they are not the only subject of the picture.

|

| • |

Contemporaries (and historians) would no doubt recognize the musicians in the Orchestra (3) or Café (4);

they are not personal portraits, but might serve as professional ones.

|

| • |

Finally, the Bar (6) and Millinery Shop (7) were clearly painted for their milieux; even when we can

identify the model, as we can in L'Absinthe, she is clearly acting a role, not present in her own

person, and thus not a portrait.

|

Here are brief bios of the artists, composers, and writers considered in the class, listed in order of birth.

|

Robert Campin, 1375–1444. Netherlandish painter.

Campin has gradually emerged from scholarly shadows as the probable painter of a handful of works previously attributed to a conjectural "Master of Flémalle." In spite of the still-uncertain identification of many works associated with him, there is no doubt of his status as a key figure in the transition of Northern art from Gothic traditions to modernity. [The portrait here is by him, but probably not of him.]

|

|

Jan van Eyck, 1390–1441. Netherlandish painter.

The most celebrated and influential northern painter in the earlier 15th century, responsible for developing a style of oil painting capable of magnificent detail and effects of light. His major work, the altarpiece in Ghent Cathedral, is recorded to have been begun by his perhaps even greater brother Hubert. He was a renowned portraitist, including the enigmatic Arnolfini Marriage in London, and the supposed self-portrait seen here.

|

|

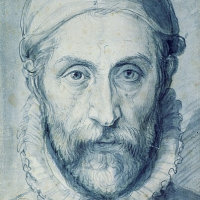

Rogier van der Weyden, 1399–1464. Netherlandish painter.

Very little is known of Rogier's life, except that he was highly successful in his time, with his works exported to Italy and Spain, and commissioned by princes both in the Netherlands and abroad. His extraordinary detail and emotionally intense compositions now place him firmly with Jan van Eyck and Robert Campin in the trinity of early Netherlandish masters. The image is a detail from his Saint Luke Drawing the Virgin, assumed to be a self-portrait.

|

|

Francesco Francia, 1447–1517. Italian painter.

Francia, whose real name was Francesco Raibolini, was an Italian painter, goldsmith, and medallist from Bologna, who was also director of the city mint. He was friends with Raphael, and painted somewhat in his style.

|

|

Domenico Ghirlandaio, 1449–94. Florentine painter.

In the same generation as Botticelli, Pollaiuolo, and Verrochio, Ghirlandaio achieved success through his ability to execute large-scale subjects that often included portraits of his wealthy patrons. He was also a remarkably sensitive in his independent portraits, including the famous Old Man and his Grandson in the Louvre. Michelangelo was one of his pupils.

|

|

Leonardo da Vinci, 1452–1519. Italian painter and polymath.

With Michelangelo and Raphael, one of the triumvirate of artistic geniuses that crown the High Renaissance. He trained in Florence with the painter Andrea Verrocchio before moving to the court of Ludovico Sforza in Milan. He spent the last years of his life at the court of François I in France. The naturalism and luminosity of his painting, and his effects of sfumato (or modeling as if by smoke), were widely influential. It is his notebooks, however, that are the best testament to the range of his genius, containing remarkable observations of the natural world, and mechanical inventions centuries before their time.

|

|

Lorenzo Lotto, 1480–1557. Italian painter.

Though born in Venice, and showing some affinity with Venetian light an color, Lotto worked mainly in other northern Italian cities. He painted many religious works, but his greatest achievement was as a painter of portraits that show both psychological penetration and often original design.

|

|

Tiziano Vecellio (Titian), 1485–1576. Venetian painter.

Arguably the greatest Venetian painter of the High Renaissance, he produced works in just about every genre over an exceptionally long career. Probably his greatest influence was in his handling of paint and use of color, which became a starting point for Rubens and others in the next century.

|

|

Hans Holbein the Younger, 1497–1543. German painter.

The son of a painter, Holbein was born in Augsburg but soon moved to Basel. He spent much of career in London, where he was court painter to Henry VIII; many of the leading figures of the time we now picture through his eyes. He favored a highly realistic style, full of details that fill out the life and circumstances of his sitters.

|

|

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, 1526–93. Italian painter.

Arcimboldo was born in Milan and began his career as a conventional portraitist. In this capacity, he entered the service of successive Holy Roman Emperors in Vienna and Prague, beginning in 1562. It was then that he developed the style for which he is now best known, painting "portraits" composed entirely out of fruit, vegetables, and inanimate objects—a sideline whose wit was much appreciated by his patrons.

|

|

Michael Praetorius, 1571–1621. German composer.

Though a polyglot and educated in theology as well as music, he began his career as a church organist and then as court musician to the Duke of Brunswick. The Duke's successor, however, encouraged him to produce religious music in what was now the Lutheran tradition. His published collections of dance music, sacred music, and theoretical writings tell us much of what we know of the music of his time.

|

|

Peter Paul Rubens, 1577–1640. Flemish painter and diplomat.

One of the giants of baroque art, Rubens developed the style of Titian into a powerful rhetoric applied equally to sacred and profane subjects, and exerted enormous influence in Spain, England, and France as well as in his native Flanders, continued in the work of his many pupils. His position at so many courts also made him invaluable as a diplomat.

|

|

Johann Zoffany, 1733–1810. German English painter.

Zoffany settled in England in 1760 after working in Rome. He was fortunate to win the patronage first of the actor David Garrick and then of King George III. He made his fortune, however, in India between 1783 and 1789, painting various Indian princes and their courts.

|

|

Franz Xaver Messerschmidt, 1736–83. German sculptor.

Messerschmidt was a Bavarian sculptor originally working in a conventional style. Today, he is best known for the series of "character heads" he produced late in his life, each grimacing in some intense emotion. There is debate, however, about whether these reflected some disorder in the artist's mind or were merely technical exercises.

|

|

Johann Caspar Lavater, 1741–1801. Swiss physiognomist and poet.

A poet, social activist, and Protestant pastor, Lavater is now best remembered for his book on physiognomy he published in the late 1770s, illustrated with silhouttes, claiming that a person's character is directly reflected in the shape of his or her features. It was widely admired, ans silhouette-take became something of a craze.

|

|

Théodore Géricault, 1791–1824. French painter.

Géricault's monumental Raft of the Medusa (1819) was a seminal work in French art, treating a contemporary political scandal with searing humanity coupled with a monumentality that owes much to Michelangelo. His many studies for this work, including corpses and severed limbs, his portraits of the insane, and above all his numerous paintings of horses, made him a key figure in French Romanticism until his death from a riding accident at the age of 32.

|

|

Robert Schumann, 1810–56. German composer.

After an injury to his hand (while studying with his future father-in-law Friedrich Wieck) prevented him from pursuing a career as a pianist, he concentrated on composing, producing some of the key works of the Romantic piano literature, together with chamber music, a concerto, four symphonies, and a wealth of songs. He was also a public figure as a critic and thinker. His career was cut short by bipolar disorder.

|

|

Edgar Degas, 1834–1917. French painter and sculptor.

The son of a wealthy banker, he originally trained for the law. When he did go into art, he painted mostly traditional subjects until Manet introduced him to the Impressionists, at which point he turned entirely to scenes from everyday life—including a good number of portraits, mostly in informal settings. Although he was the only artist to participate in all eight Impressionist shows, he strongly resisted the term, and pursued his own quite original course.

|

|

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, 1834–1903. American painter, working in London.

Whistler's American father was a railroad engineer who took work in Russia when the future artist was still a child, so his training and career took place almost entirely in Europe. He was famous for giving his near-abstract paintings titles such as Arrangement in Grey and Black (the portrait of his mother), thus emphasizing the connection between painting and music.

|

|

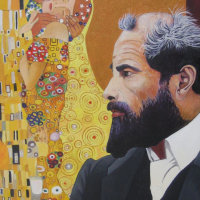

Gustav Klimt, 1862–1918. Austrian painter.

Klimt was the foremost painter of the Vienna Seccession at the turn of the century. He specialized in female subjects, some taken from myth, painted in a highly-patterned Symbolist style, erotic and richly colored, often with the addition of gold leaf. His Danaë of 1907 is a prime example.

|

|

Isaak Brodsky, 1884–1939. Russian painter.

Brodsky "was a Soviet painter whose work provided a blueprint for the art movement of socialist realism. He is known for his iconic portrayals of Lenin and idealized, carefully crafted paintings dedicated to the events of the Russian Civil War and Bolshevik Revolution" [Wikipedia].

|

|

Joan Tower, 1938– . American composer.

Tower began her career as a pianist, especially with the NY ensemble Da Capo Players, which she co-founded. Simultaneously, she was establishing a reputation as a composer, including a series of six works called Fanfare for the Uncommon Woman, each honoring a different American Woman in music.

|