4. Treading the Boards.

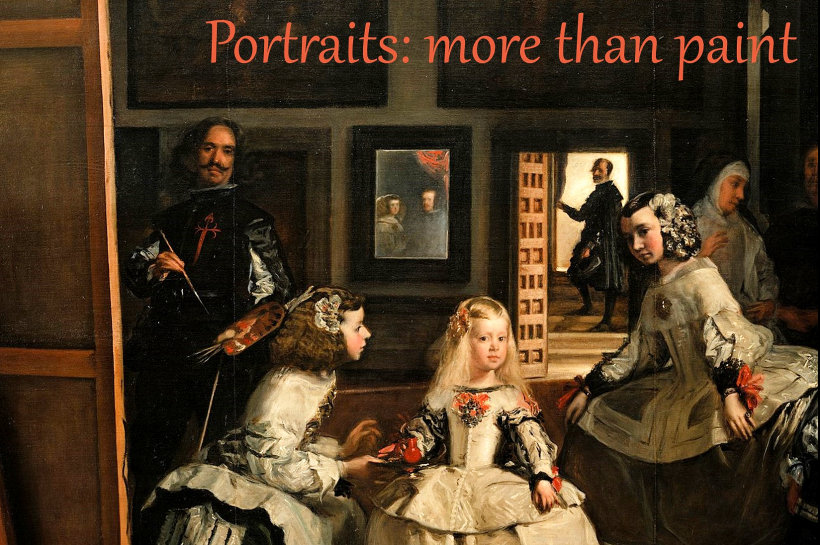

Presenting the life of a real person on the stage is not in itself the equivalent of painting their portrait.

For one thing, the action of a drama is quite different from the stillness and inner focus of a good portrait.

Secondly, most portraits arise from a present-tense interaction between artist and sitter, whereas the

subjects of most bio-dramas are long since dead.

This class will consider some exceptions to this: the role of a Shakespearean soliloquy or operatic aria in

creating the needed stillness and penetration; the fact that a live actor on a live stage (we are excluding

film) brings the character into a different kind of present tense; and a few special works created around

figures who were still living at the time of their premiere.

Given the topic, the class will consist almost entirely of video clips, introduced with the minimum amount of

discourse, but preferably interspersed with discussion.

The script, videos, and images will be posted immediately after class. rb.

TO THINK ABOUT

The class will begin with the opening speech from Shakespeare's Richard III; I strongly suggest that

you read it in advance. The situation is this: the Wars of

the Roses are over; Richard's brother, the Duke of York, is on the throne; Richard himself is not merely a

"spare"—he is way down the line of succession, and intends to do something about that. I have divided the PDF

into three sections; what does Richard do in each, and how do all three combine to give us a "portrait" of

his character?

I had thought to include also in the class Evita Peron's famous song "Dont cry for me, Argentina" from the

1978 musical Evita by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice. But the only good videos I could find are of

concert performances (lots of them!) and the 1996 movie, and as I am confining myself to stage

performances, I decided not to use them. Nevertheless, I invite you to compare performances of the song by

the original stage Evita Elaine Page at a Royal

Albert Hall tribute over 40 years later and by Madonna

in the movie. I suggest you watch the Page concert first, because if you click [CC] at the bottom of

the screen, you will get the words, and I want you to think how words and music work together without any

stage context to paint a portrait of the character. Then see whether the visuals and added production elements

of the movie add to this—or perhaps detract?

Here are brief bios of the artists, composers, and writers considered in the class, listed in order of birth.

|

William Shakespeare, 1564–1616. English poet and playwright.

With almost 40 plays, 154 sonnets, and many longer poems, Shakespeare dominates English literature of his time, and world literature for ever after. To attempt a thumbnail biography would be both unnecessary and impossible.

|

|

Giuseppe Verdi, 1813–1901. Italian opera composer.

Verdi's two dozen or more operas (depending on how you count them) make him the leading Italian opera composer of his time and among the two or three greatest opera composers ever. After what he called his "years in the galleys," he hit his stride in the early 1850s with the trio of Rigoletto, Il Trovatore, and La Traviata. He intended Aïda to be his last work, but was persaded out of retirement to write his final Shakespearean masterpieces: Otello (1886) and Falstaff (1893).

|

|

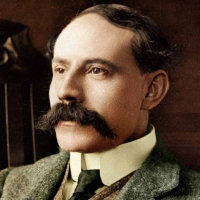

Edward Elgar, 1857–1934. English composer.

Elgar was the leading figure in English music during the late Victorian and Edwardian eras. With works such as the Enigma Variations and his concerti for violin and cello, he was one of the first English composers after Purcell to achieve an international reputation.

|

|

Micheál MacLiammóir, 1899–1978. Irish actor and writer.

MacLiammóir ended his life justly celebrated as one of Ireland's greatest actors and playwrights (in both English and Irish); he was also a co-founder of Dublin's famous Gate Theatre. But he was born Alfred Lee Willmore in the London suburb of Willisden to a family with no Irish connections whatsoever; the persona under which he led his entire life was totally his own invention.

|

|

Frederick Ashton, 1904–88. English choreographer.

Like most choreographers, Sir Frederick Ashton began as a dancer, and continued performing even as his fame blossomed as a choreographer. He became artistic director of the Royal Ballet in 1963, but had worked with the company and its various predecessors since 1935, responsible for creating many of the works that are the foundations of English ballet today.

|

|

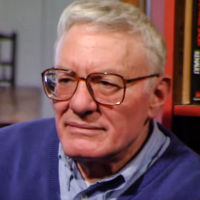

Peter Shaffer, 1926–2016. English playwright.

Sir Peter Shaffer's plays have been associated with the English National Theatre since its founding; they include The Royal Hunt of the Sun (1964), Black Comedy (1965), Equus (1973), and Amadeus (1979). He was the twin bother of mystery playwright Antony Shaffer, author of Sleuth (1970).

|

|

Terrence McNally, 1938– . American playwright.

McNally wrote more than 40 plays over a span of six decades, winning most of the awards in the American theater. He also wrote the books for musicals such as Ragtime and The Full Monty and the libretti for three operas by Jake Heggie, including Dead Man Walking in 2000.

|

|

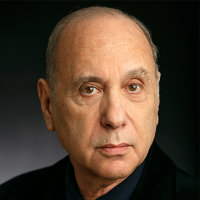

Marshall Brickman, 1939– . American screenwriter.

As a screenwriter, Brickman was best known as a collaborator with Johnny Carson and Woody Allen, sharing an Oscar for the screenplay of Annie Hall. With his partner Rick Ellice, he wrote the book for Jersey Boys in 2005.

|

|

Philip Feeney, 1954– . English composer.

After studies at Cambridge and in Rome, Feeney made a name for himself as a composer of ballet and modern dance. He has created over 40 scores for Ballet Central in London, plus others for Northern Ballet Theatre, the Martha Graham Company, and the Royal Ballet. His score for Cathy Marston's The Cellist (2020) includes references to the many works famously associated with its subject, Jacqueline du Pré.

|

|

Rick Elice, 1956– . American actor writer.

Born in NYC, Elice studied at Cornell and Yale, then taught for a year at Harvard. After working as an actor, he moved backstage as an impresario, a creative consultant for Disney, and (with Marshall Brickman) writer of the 2005 show Jersey Boys.

|

|

Mark-Anthony Turnage, 1960– . English composer.

Turnage's operatic work includes Greek (1988, the Oedipus story relocated to the East End of London), The Silver Tassie (2000, after the play by Sean O'Casey), Anna Nicole (2013, with libretto by Richard Thomas), and Coraline (2018, after a novella by Neil Gaiman).

|

|

Jake Heggie, 1961– . American composer.

Heggie came to fame as an opera composer in 2000, with his adaptation of Dead Man Walking by Sister Helen Prejean, who appears as a character in the opera. He went on to write an operatic version of Moby Dick (2010), a dramatically impressive condensation of Melville's huge book, to great critical acclaim.

|

|

Richard Thomas, 1964– . English librettist, comedian, and composer.

Thomas won four Olivier awards for his 2001 musical Jerry Springer: the Opera. A pianist, performing comedian, actor, and television presenter, he also wrote the libretto for Mark-Anthony Turnage's 2011 opera Anna Nicole (see below).

|

|

Nkeiru Okoye, 1972– . American composer.

Born in New York, Okoye has an African American mother and a Nigerian father, and he childhood was divided between both countries. No stranger to the large stage, she has writen an opera on the life of Harriet Tubman, and several projects commissioned by US symphony orchestras.

|

|

Cathy Marston, 1975– . English choreographer.

Trained at the Royal Ballet School in London, Marston began her career as a dancer in Switzerland, with the ballet companies in Bern, Luzern, and Zurich. She later became Artistic Director at Bern, and now occupies the same post in Zurich. Her independent works as a choreographer include Jane Eyre for Northern Ballet, Victoria for the National Ballet of Canada, and The Cellist (2020) for the Royal Ballet.

|

|

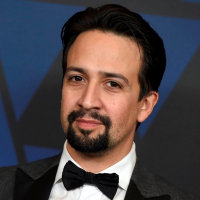

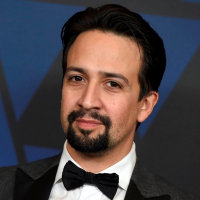

Lin-Manuel Miranda, 1980– . American composer.

As the playwright, lyricist, composer, and star performer in his 1915 mega-hit Hamilton, Miranda became an unheard-of quadruple-threat on Broadway. He had shown many of the same talents, however, in his 2005 musical In the Heights, and has since developed his career further into film (both acting and directing).

|